Jade Mountain, St Lucia: The Caribbean island paradise epitomising slow luxury travel

How two visionary hoteliers turned fantasy into reality on St Lucia’s west coast

“I’ll tell you the short version,” Karolin Troubetzkoy, executive director of Jade Mountain in St Lucia, chuckles as she tops up my wine. It’s how most of the hotelier’s stories begin, and even the ‘short’ ones would fill a hardback. From the marijuana pouch she crocheted for a guest, to Princess Margaret advising her that “one must never run out of Earl Grey”, Troubetzkoy is as entertaining as she is well-connected.

Having grown up in her aunt’s hotel near Munich, Troubetzkoy first visited St Lucia in 1980 – “my mother said I was mad, so, naturally, nothing could stop me”. Four decades later, she’s as much a part of the island’s story as the two hotels she runs with her husband, architect Nick Troubetzkoy.

The couple opened neighbouring properties Anse Chastanet and Jade Mountain, on the same plot of land, in 2000 and 2006 respectively. Thanks to the Troubetzkoys’ visionary approach, both properties feel futuristic even now. “I don’t like the word sustainability,” says Karolin. “It’s overused. Everything we do is about leaving something better behind.”

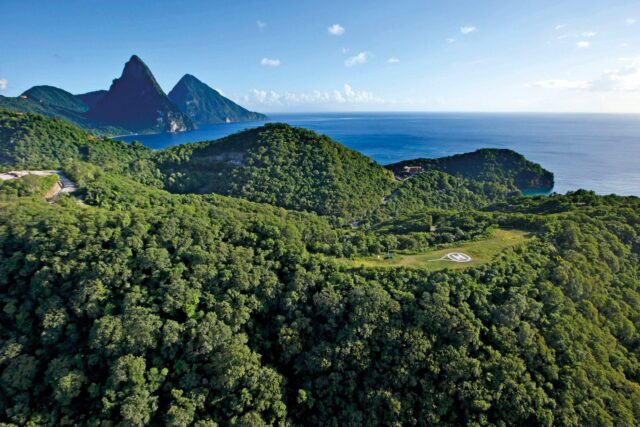

Sure, the 600-acre resort falls firmly under the ‘luxury’ umbrella – there’s a Prince Harry-approved heliport, in-room massage therapists (ask for Phillippa), champagne-fuelled sunset cruises and your own ‘major-domo’ butler – but the real luxury here is the location. A short, bumpy drive from the port town of Soufriére on St Lucia’s west coast, the resort encompasses two beaches, two hotels – Anse Chastanet has 49 rooms; Jade Mountain has 79 – and the Emerald Farm estate, where the Troubetzkoys live.

Nearby, Soufriére’s sulphur springs offer medicinal mud baths and the island’s botanic garden bursts with sleeping hibiscus, wax begonia, athenium lilies, elephant ear and lobster claw. Every view at Jade Mountain is angled towards St Lucia’s most iconic landmark, the volcanic peaks of the Pitons – and the hotel has become something of a landmark itself.

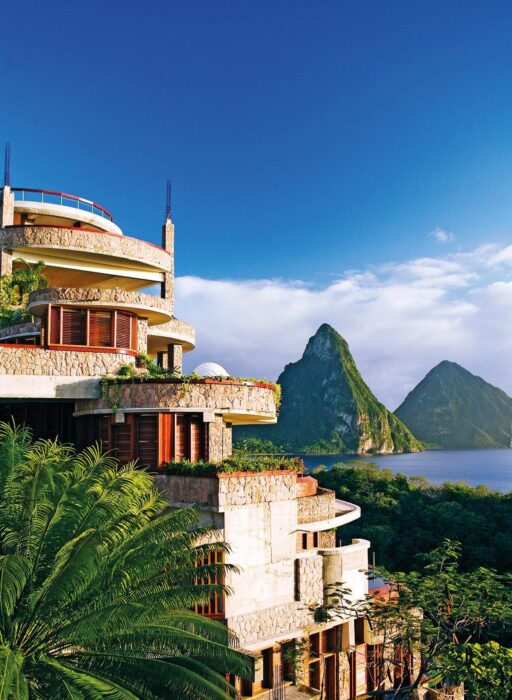

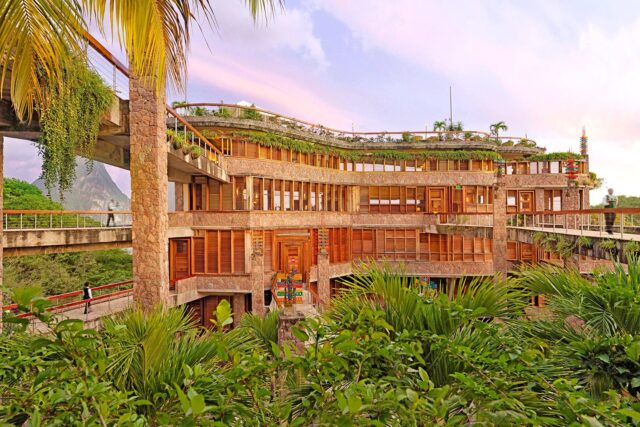

While your average hotelier might settle for Jade Mountain’s prime Piton-viewing position as its sole USP, visionary Nick Troubetzkoy is anything but average. The hotel’s name itself comes from Nick’s collection of exquisitely-carved jade sculptures – the largest collection in the world. Artisans spend a lifetime mastering the craft, and elements of their singularly improbable nature can be found throughout the hotel’s extraordinary design. During Jade Mountain’s conception, Nick consulted designers, architects and engineers – all of whom told him that it would be impossible to make his vision a reality. He proved them all wrong.

It’s difficult to prepare for the visual impact of the hotel’s limestone pillars and criss-crossing bridges. Jade Mountain could be a perfectly preserved ancient city, or a portal to another planet; it’s a cinematic rendering of a fantasy, conjured by a mind for which the limits of science are merely challenges to overcome.

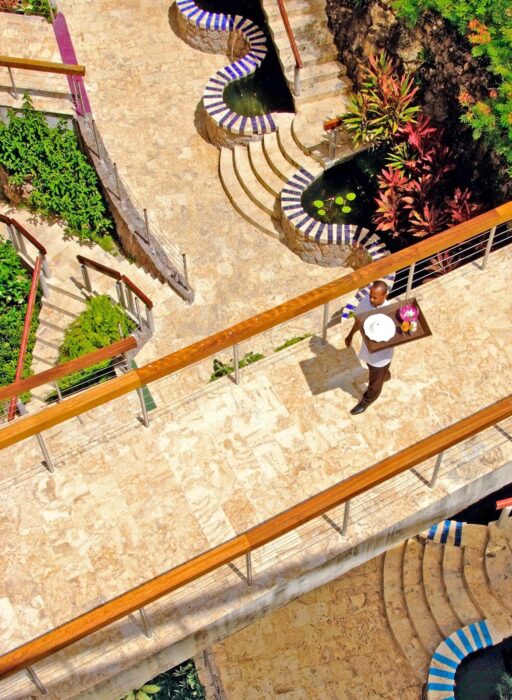

At the centre of the resort’s design is the concept of ‘watershaping’, in which structures use water in artistic ways. “With no water, there’s no Jade,” says property manager Carl Hunter, who explains the lengths they went to in excavating an old water reservoir to provide for the hotel and local village, and shows me around the in-house water bottling facility and man-made wetlands. Beyond its life-giving qualities, watershaping springs from an appreciation of the way water moves and makes us feel; the way it interacts with light and alters perception.

Spread out over six levels, each of Jade Mountain’s 25 ‘sanctuaries’ has its exterior wall missing to accommodate its very own unique infinity pool from which to enjoy uninterrupted views of the ocean and the Pitons. From a certain angle, the blues melt together and I almost believe that I could push off from the steps of my pool and come up for air in the shallows of the Pitons. Even the sky plays up to its role: clouds intermittently snag on the peak of Gros Piton and shimmery pink sunsets are refracted back and forth between the sea and sky. The fluid, open-air effect is ethereal and elicits a sense of freedom – there’s a thrill in sleeping with one less barrier between you and the great outdoors.

Adjacent Anse Chastanet is thought to be one of the first hotels to offer jungle biking, but the humidity is hair-raising enough for me. Instead, Joevan Gabrielle guides me through the rainforest on foot, handing me sherbet-sour cacao beans, pointing out ginger lilies and hummingbirds. The place is a playground: he recalls how kids turn the seeds of ‘shack shack' trees into maracas; how they’d trap birds on branches using gum from the breadfruit trees; how bamboo shoots can be turned into makeshift fireworks.

Along a path that even I could have managed by bicycle, we come to a crumbling structure that the jungle has almost entirely enveloped and the tales of beauty give way to those of brutality. Decaying 18th-century machinery signals that we’re standing in what used to be a sugar plantation, where around 600 enslaved people were forced to work under French rule. For reasons I can’t fathom, it’s a popular spot for weddings.

Later, I learn that as well as lead bike guide and unofficial historian, Joevan is also a scuba diving instructor. Many of the staff are multi-taskers, something that Karolin encourages. During Covid-19, she was craving home-baked goods, and she knew that Joevan’s fellow scuba-diving photographer, Bernd, was a baker in a past life. “He gave me a sourdough starter from his family that’s more than 200 years old,” she says. Now, the bread is on Frank Faucher’s vegan menu at Anse Chastanet’s Emeralds restaurant. It’s easily one of the most original and impressive meat-free menus I’ve come across – quite a feat, on an island the size of Chicago. Faucher’s fragrant Ital stew is his mother’s recipe and consists of breadfruit, dasheen, carrots and coconut milk, topped with moringa and microherbs grown on nearby Emerald Farm.

While farm-to-table dining is exactly what the resort’s restaurants deliver, Nick and Karolin are careful to ensure that the farm doesn’t create competition with local producers. As a result, the team of young, agile farmers have space to experiment, toying with mushroom cultivation and beekeeping. The honey has been a huge success, and they’ve even created Antillia Brewing Company – their small-batch passionfruit ale is a brilliant beach beer, best sipped cold straight from the can.

One of the farmers, Imran, shows me around. He tells me that his grandparents used to manage the farm, and he’s proud that everything they produce here is organic. For 2023, there are plans to build an outdoor bar and dining space on the farm, but for now, chef Eli Jules hosts informal live cooking classes at a pop-up kitchen. He’s full of energy and his food is as vibrant as he is. He counts himself lucky: “There are no culinary schools in St Lucia, but Karolin has nurtured me.” From the table, you can see the brightly-coloured rooftops of Soufriére, where Eli pays it forward by teaching kids in the secondary school how to cook. “Most of my team are students that came up through the school and found a passion for food.”

Karolin might hate the word ‘sustainability’, but by treating her hotel as a force for change, a platform for education, a fortress of slow travel and a community space, she’s ensuring that Jade Mountain’s legacy is an enduring one. I might have only got the ‘short version’, but it’s clear that Jade Mountain’s story has just started.

Rates at Jade Mountain start at £1,500 per night in a Sky Sanctuary, visit jademountain.com; rates at Anse Chastanet start at £380 per night in a Standard Room, visit ansechastanet.com

Read more: Sommerro, Oslo: Norway’s coolest hotel effortlessly blends Scandinavian luxury and subtle escapism