Priya Ahluwalia is the real deal

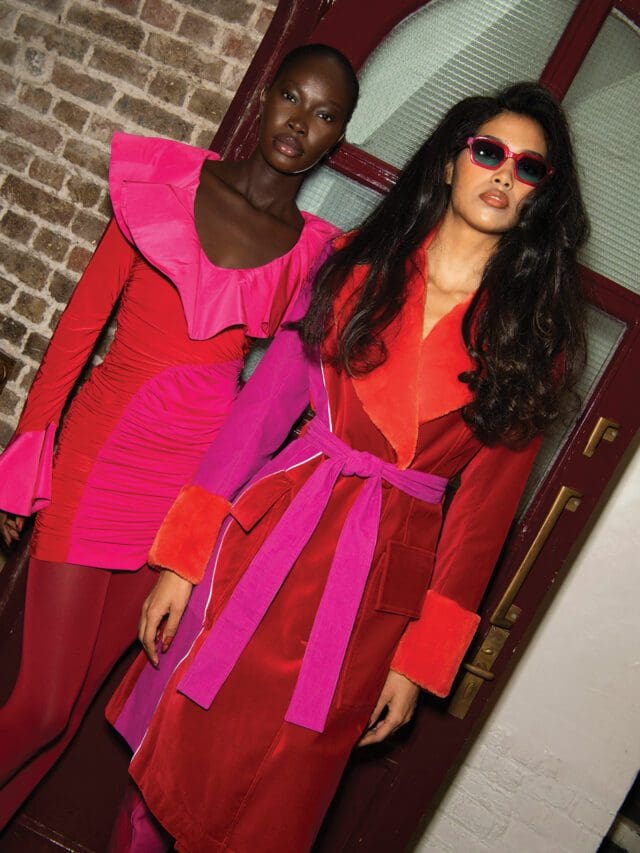

Priya Ahluwalia's idiosyncratic designs, informed by her dual heritage and use of second-hand materials, have elevated her to fashion royalty. Yet, says the Indian-Nigerian designer, heavy is the head that wears the crown

Priya Ahluwalia is not a people-pleaser. She possesses an insouciant freedom from the conventions of polite conversation that I imagine is probably quite liberating – she doesn’t coax or encourage, doesn’t ‘mmm’ and ‘yeah’. She didn’t even turn on her video during our Zoom call, citing technical issues. She’s amiable, sure. Just not the sort of person who offers it all up on a plate.

Which, after years of doing interviews with people ‘in fashion’, I can tell you is rare. Usually, you give a spokesperson a soapbox and they’ll regurgitate their entire press pack. Ahluwalia is the polar opposite. She’s not going to pitch for you. She won’t rerun the same old soundbites. Far from it.

“I was just so bored of everyone talking about [sustainability],” Ahluwalia told GQ in 2020. Which is not the sort of thing you typically hear from the mouth of a high-profile designer – especially one that was named ‘Environmental Leader of Change’ at the British Fashion Awards in 2021; someone whose label has been known since its 2018 inception for working with deadstock materials.

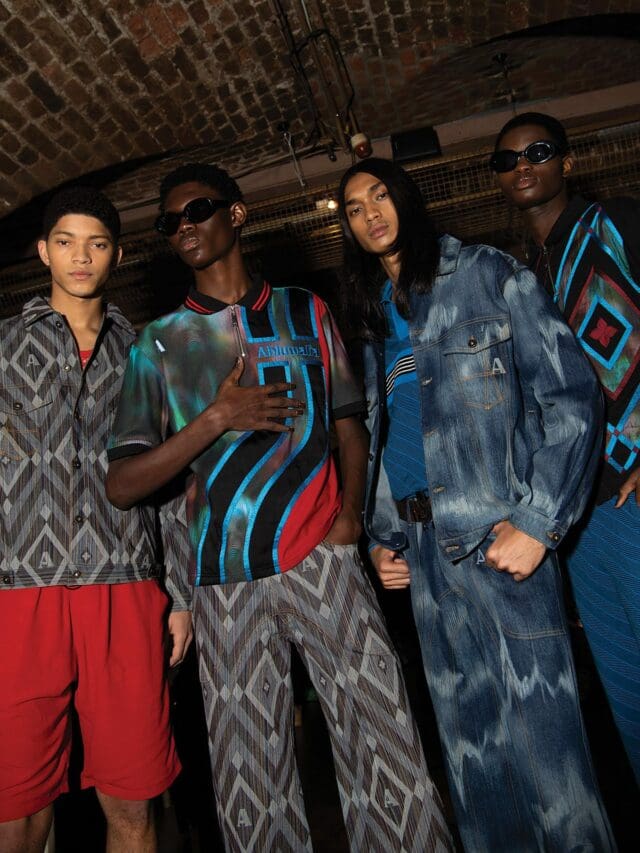

Looking through any given collection, you can feel it: the quirky, multilayered, slightly frenetic style that comes with scouring warehouses for recycled offcuts. “I like things with depth,” says Ahluwalia. “That really comes with using deadstock, because when you don’t have enough material to make a full garment you start to patch things together. That’s rubbed off on my aesthetics – even with a really slick piece, there’s always depth to it.”

Naturally, I’m keen to find out how she reconciles this approach with her comments: “The reason I sometimes get frustrated is not because I don’t think [sustainability] is important, but I think it takes away from the fact that I’m a designer and a creative and I’m good at my job,” she says. “It makes people just want to talk to me about, like, organic materials, and that’s a fraction of it.”

It’s an unconventional position, to be sure, but refreshing. On the other end of the spectrum, you have brands touting their green credentials until they’re blue in the face, even if they don’t really have any. But here’s a designer who actually does do the sustainability thing, declining to comment on it. Is Ahluwalia the anti-greenwasher, providing a much-needed antidote to virtue-signalling labels?

“[Greenwashing] is not something that happens among my peers. We are trying our best, and I think that’s all that you can do,” she says. “We need to ask these questions to people that can make systemic change, because everything I’m doing is a blip in the ocean; it’s a speck in the universe. But there are companies that could shift the needle, and that’s where the sustainability conversation needs to be focused.”

My question on diversity – a huge buzz-topic in the industry right now, with debates raging around plus-size models, age representation, and the number of non-white designers at Fashion Week – ricochets in a similar fashion. As a designer of black and South Asian descent (her mother is Indian; her father is Nigerian), I thought that Ahluwalia might have something to say on the matter. She did, of course – just not what I expected.

“I don’t want to come across as rude. But this question, it’s quite funny to me, because I’m obviously not a part of the problem. I have a team of 10 people; there are nine women, one man, 90 per cent of us are black or brown or a mixture of both. So, like, I don’t have a diversity issue in my business. That’s not an issue that I perpetuate. So I don’t really know.” She offhandedly cites “white supremacy” and the “fetishisation of youth”, but it’s clear we won’t be chowing down on any meaty socio-political issues today.

Just as Ahluwalia refuses to be pigeonholed as a ‘sustainable designer’, she doesn’t want to be lumped into a non-white ‘box’. Unlike when she was growing up in the 1990s and ’00s, there is now a substantial cohort of POC-owned labels rising through the ranks – Mowalola, Wales Bonner and Saul Nash, to name just a few. “These designers, they’re showing their authentic representation of what it is to be black or brown – there isn’t a one-dimensional representation of it, because that’s not life,” says Ahluwalia. “All our creativity is different. I don’t like to be reduced to being just a black or brown designer, because there’s a multitude of things that means for different people.”

The more I nudge Ahluwalia towards the soap box, the more it becomes clear that she doesn’t want to go there. Is it important for the creation of a well-adjusted society that people are exposed to different cultures, I wonder, dangling the bait? She ignores it. “I don’t want to answer. I don’t know. I don’t really understand why it’s up to me to discuss what other people need to be doing to be well-rounded, to be honest.”

OK. Enough of politics. Enough social issues. Enough probing for preachy soundbites that Ahluwalia is clearly loath to give. Who is she as a designer, away from buzzwords and box-ticking? She is a designer whose memories of her home countries inform her ideas – she takes cues from Indian embroidery and the streetwear of Lagos: “Everything that I have grown up with is naturally going to influence my work. The music I have listened to, Nollywood and Bollywood cinema, family photos, artefacts…”

London, Ahluwalia’s hometown, is another source of inspiration: “It’s a melting pot and that influences the way I look at things. I like syncretism.” The designer’s Tooting upbringing directly informed one collaboration with Clarks, in fact, which spoke to a collective experience of London kids: traipsing to the shop to get their school shoes. “Those sort of moments define your taste forever, right?”

“There are companies that could shift the needle, and that’s where the sustainability conversation needs to be focused”

Priya Ahluwalia

Ahluwalia started as a menswear label (the company has only been doing women’s collections since 2021), once again taking cues from a patchwork of sources: Indian and Nigerian street style, male celebs like Donald Glover and A$AP Rocky, Savile Row tailoring. The designer was drawn to men’s clothing for the simple fact that, traditionally, the category has been so much more limited than women’s – Ahluwalia wanted to see whether she could mix it up. “Men have been wearing pretty similar things for the past 50 years. I liked the idea of having the opportunity to push those boundaries – to play around with the codes of menswear.”

What else? She is a designer who loves to use mixed media: “When I’m creating a season, I read a lot, I watch a lot of films, and I visit exhibitions and galleries. All of that feeds into this bank of research that I have, and I curate projects from that.”

Ahluwalia’s latest ready-to-wear collection, Symphony, is inspired by the music that has shaped her life, including artists like Sade, Lauryn Hill and Mobb Deep, with a dose of Prince and Queen, and a sprinkling of Punjabi and Nigerian beats. In 2020, Ahluwalia participated in GucciFest, where she created a short film called Joy; she fell in love with filmmaking and, at the end of last year, was signed to Black Dog Films.

What about Ahluwalia the person? She loves getting dressed up, and her nails are always immaculate. “The way that I like to accessorise and look, I’m definitely like a London girl,” she says. “That said, there is definitely time for a tracksuit. I mean, I wear a tracksuit to work.”

When I ask Ahluwalia about her favourite music artists, something shifts – for the first time, she relaxes and enthuses: “Oh God, it’s so difficult. I don’t know how to answer because I just love so much stuff. Okay, I’m gonna say Sade.”

The matter of her favourite film is equally torturous – maybe 1998 Hindi musical Kuch Kuch Hota Hai – but she settles on Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (an historical fiction about slavery) as the book that has changed her life. On the subject of books, Ahluwalia’s SS24 collection was shown at the British Library, which she says “speaks to [her] love of literature”. She keeps a notepad by her bed and writes something every day.

Ahluwalia says she’s a party girl trapped in a homebody, conceding that she’d rather be out on a Friday night, but usually stays in. She loves the food that her Indian nana cooks, rivalled only by goat suya (a Nigerian kebab). “This is the tricky thing about being mixed race,” she laughs. Her favourite person in the world is her mum.

“Black and brown people should just be able to have joy,” says Ahluwalia towards the end of our interview. “I think that I should be able to just enjoy putting nice things out without having to be some sort of representative to fix the whole world.”

Suddenly, her reticence makes sense – it must be exhausting, constantly politicising your existence. And I saw how she came alive when she was allowed to talk about her passions, rather than having to hash out the whole fashion world’s ills. Here is a complex, multi-layered individual – not a mouthpiece. She doesn’t have all the answers, and has never claimed as much.

“Everyone thinks I’m some sort of political spokesperson,” says Ahluwalia. “I just represent an authentic experience.”

Visit ahluwalia.world