Battersea Power Station one year on: Has the landmark renovation been a success?

13 months after it was reopened as a residential and retail mixed-use scheme, Luxury London visits Battersea Power Station to see how the developer has honoured its iconic heritage

On 14 October 2022, hundreds gathered in Nine Elms to witness the reopening of Battersea Power Station. Crowds chanted the countdown to one, at which point streamers rained down and cheers filled the air – not the typical response to the launch of a mixed-use development, I think it’s fair to say.

But Battersea Power Station is different. It’s been sitting there, on the bank of the Thames, for as long as anyone can remember – derelict, ailing, but an inherent part of Battersea’s identity. The news of its renovation captured people’s imaginations in a way that The Leadenhall Building or 22 Bishopsgate never could.

A potted history, then: Battersea Power Station actually comprised two stations, ‘A’ Station was completed in 1935, and ‘B’ in 1955. By the ‘70s, the building’s equipment was outdated, as was coal itself, and the towers were decommissioned in 1975 and 1983 respectively. They then stood derelict until 2014, with successive site owners musing over the question of what to do with it; ultimately, the land was bought by a consortium of Malaysian investors to develop into residential, commercial and office units.

Battersea Power Station’s reconstruction was a monumental task. When the consortium bought the space, it was completely derelict, with trees growing inside its walls. The chimneys were under a Dangerous Structures Notice, and all four had to be dismantled and rebuilt to the precise specification of the originals. The bricks were badly damaged; remarkably, the two brickmakers that made the originals (one of which was a firm founded by the World War I hero and art collector Captain E G Spencer-Churchill, a cousin of Winston Churchill, and is still based at the same Gloucestershire quarry as it was all those years ago) were tracked down and tasked with making 1.75 million more.

The plans had their detractors, of course. After schemes to turn the Power Station into a football ground and a theme park were floated, some felt disappointed that this iconic building was to be turned into yet more Zaras, Prets and pricey homes. It and every other heritage building that has come on the market in the last 20 years, right?

This argument, however, does not take into account the fact that, prior to the regeneration of the Power Station, there was nothing here but industrial brownfield. Its reopening has completely transformed Nine Elms (the Power Station itself, the hulking redbrick structure that we know and love, is only a portion of the project – one phase of eight, of which three have been delivered thus far). The entire 42-acre site is commensurate with a brand new district, complete with a new Northern Line station.

Public opinion would, of course, depend on what the Battersea Power Station Development Company did to the structure and its surrounding areas. Would it become another soulless casualty of late-stage capitalism – a hellscape of bao buns and second homes? Or would it honour the Grade II* listed building’s history?

I decided to see for myself. To mark Battersea Power Station’s one-year anniversary, I was offered a tour of the completed phases. So, how has one of the biggest-ticket, but also the most culturally important, London refurbishments of the 21st century been pulled off?

Fortunately, the day of the tour was glorious, which is how the chimneys look best: against hazy, uninterrupted blue. It didn’t feel particularly busy, but perhaps that was due to it being mid-morning on a Monday. I started in Electric Boulevard, which was the third phase of the development to be completed, named for the fact that, at the peak of its production, the Power Station provided a fifth of London’s electricity.

Turbine Hall A

Turbine Hall B

Then it was onto the Power Station itself. The body of the building is now home to hundreds of shops, a cinema, and a glass chimney lift experience, among other retail and entertainment offerings, as well as Apple’s London campus (over 6,000 workers are now based at Battersea Power Station), and hundreds of new homes (more on this later).

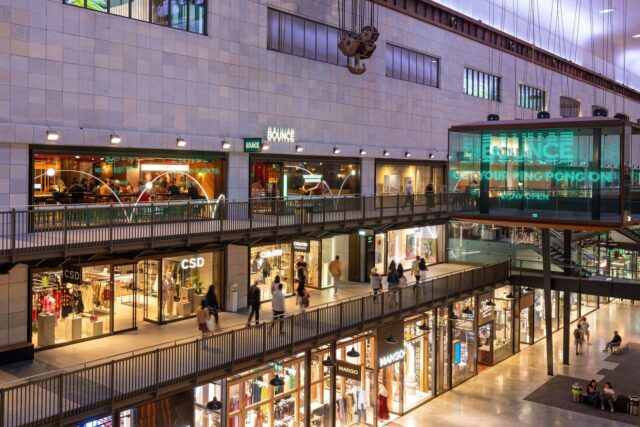

As mentioned, Battersea Power Station was built in two stages, and the retail offering is designed along these lines. The space is split between Turbine Halls A and B; the former leans into the Art Deco provenance of the building, with details like an original Greek key pattern still visible on balconies, which has then been replicated on new balustrades. The old gantry cranes and travelling rail have been left, as have the marks where the crane knocked into the faience. Markers of where the old turbine machinery would have stood have been laid in brick on the floor.

Meanwhile, Turbine Hall B reflects 1950s modernism. The faience is unadorned, yet the space still recalls the second phase of the Power Station's life: again, footprints of the turbines are laid in brick and one of the gantry cranes has been restored. The Hall’s control room has been reopened as a cocktail bar, set in among the original dials and controls. In the North and South Atriums, where you enter the Halls, the original brick walls and steel beams have been left exposed. In the former, you can see remnants of staircases and bits of tiling from old washrooms; in the latter, the wall is supported by a vintage bow string truss.

In terms of the offering, the Turbine Halls contain a good mix of chain and independent stores and eateries, with all of your major players checked off. Particularly impressive (although perhaps I get this impression because it was, by this point, nearing lunch) is the 24,000 sq ft, 500-cover Arcade Food Hall.

As someone who often (reluctantly) finds themself in Stratford Westfield, my first impression of Turbine Halls A and B is one of blissful serenity. Sure, it’s Monday morning, but I don’t think it’s just that. Firstly, these areas are massive; central to the proposals given to architectural practice WilkinsonEyre was that visitors should be aware of the scale of the building, which meant not splitting up or compartmentalising the Halls. Second, colours and lighting are muted, so you don’t get the dentist’s-chair-fluorescent-lighting vibe of other malls.

Koa at Electric Boulevard

Battersea Power Station is also home to 2,500 people living across three residential schemes: there are the apartments within the Power Station (including 18 Sky Villas); Circus West Village, a neighbourhood of 1,800 residents; and Electric Boulevard, which is comprised of Prospect Place, Koa, and Battersea Roof Gardens.

The 204 studio, one- and two-bedroom apartments at Koa, which is designed by Foster + Partners, feel characterful and fresh. Two colour palette options bring different qualities: ‘Dawn’ has bright white kitchens and light stone tiling, while ‘Dusk’ is its darker inverse. I was particularly taken by the 8,350 sq ft Sky Lounge spread across the top two floors; residents also enjoy access to one of London’s largest residential rooftop gardens.

Prospect Place

Prospect Place, which is architect Frank Gehry’s first residential building in the UK, resides opposite. No two apartments here are the same; purchasing a Gehry apartment, claims Battersea Power Station, is similar to buying a one-of-a-kind artwork. The apartments, again, come in two colour schemes: ‘London’ – which reflects the historical elements of the development with a streamlined, industrial feel – and ‘LA’, which is more relaxed, with pale wooden finishes and light colours.

Finally, the Sky Villas are the jewel in the crown – the collection sits atop the Power Station, right between the chimneys and set around communal garden Boiler House Square. Duplex, dual-aspect apartments boast private gardens, balconies and roof terraces, with design features such as steel staircases and Crittall-style windows. Again, interior architect Michaelis Boyd has created two palettes: ‘Heritage 33’ takes inspiration from the styling of the ‘30s, with dark herringbone flooring and glazed tiles, while ‘Heritage 47’ showcases an industrial aesthetic to demonstrate the pared-back style of the ‘50s.

There is no doubt about the fact that Battersea Power Station has done everything in its power to honour its heritage; realistically, it couldn’t have been any other way. The best parts are when this nod is most pronounced – if you squint your eyes in the elevator shaft to the Sky Villas, you can almost imagine yourself back in the 1930s. Turbine Hall A, similarly, captures the spirit of Art Deco as well as a mall possibly can. The surrounding area is pleasant, if not quite grown into its new status as a bustling urban district.

Whatever your opinion on how the development has taken shape, one can’t help but be in awe of the scale of the project and the change that it has engendered. By the time it is complete, 25,000 people will be living and working at Battersea Power Station. Across the site, there will be 250 shops, cafes and restaurants, a theatre, a hotel, a medical centre, and a six-acre public park. Whichever way you square it, the development has put Battersea on the London map in the same way that its predecessor did.

Visit batterseapowerstation.co.uk

Read more: Festive cheer: The best Christmas events in London in 2023