Time To Move: What Swatch Group Did Next

Horological highlights at the 'Time to Move' Swatch Group soirée

“The MCH Group, which organises Baselworld, is clearly more concerned with optimising and amortising its new building… than it is in having the courage to make real progress and to bring about true and profound changes. For all these reasons, Swatch Group has decided that from 2019 onwards, it will no longer be present at Baselworld.” Ouch.

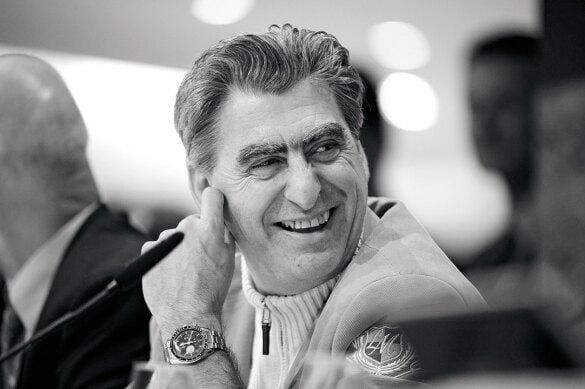

Ever since Hayek’s stinging rebuke, delivered via a press release in July 2018, there had been speculation as to what the Swatch Group patriarch would do with the 50 million Swiss francs it reportedly cost him to exhibit his 17 brands at the world’s largest watch fair, Baselworld.

The answer arrived in March in the form of an invitation to the irreverently-named ‘Time to Move’, a week-long, two-fingered-salute to Baselworld that would take watch press on a whistle-stop tour through Switzerland’s watchmaking heartlands. On the itinerary were visits to the ‘manufactures’ of six of Swatch’s most prestigious houses: Blancpain and Breguet in the Vallée de Joux; Harry Winston and Glashütte Original in Geneva (Glashütte showcased its latest creations in a hotel, the brand hailing from Germany); Jaquet Droz in La Chaux-de-Fonds; and Omega in Biel.

Following lab-coat tours of each brand’s state-of-the-art workshops, we got down to the serious business of spanking new timepieces. These were the half-dozen timepieces that grabbed the headlines from Swatch Group’s inaugural soirée…

Apollo 11 50th Anniversary Limited Edition, Omega

Omega CEO and President Raynald Aeschlimann has been candid about his ambition to out-sell market-leader Rolex – and he’s certainly got the production facilities to do so. In November 2017, Omega extended its Biel-based HQ with a new building by Japanese starchitect Shigeru Ban. With indoor climate control and air-flow technology (used to flush away that scourge of precision watchmaking – dust), the cavernous five-storey factory features a fully-automated, fireproofed storage facility that rises through three entire floors. It contains more than 30,000 boxes of watch components, allowing Omega to manufacture 3,000 timepieces a day – according to Aeschlimann. (Given that there are 261 working days in a year, GQ’s maths suggests that Omega is churning out just shy of 800,000 watches annually. Rolex reportedly makes around one million).

The hotly-anticipated Apollo 11 50th Anniversary Limited Edition proved to be the watch of the show (perhaps of the year). Designed to commemorate 50 years since the Speedmaster became the first watch on the moon, the 42mm stainless steel timepiece features a bezel, indexes, hands and logo in ‘Moonshine’ gold – a new alloy, slightly paler than traditional yellow gold, that, says Omega, is more resistant to fading. A laser-engraved image of Buzz Aldrin descending from the lunar module appears in a subdial at 9 o’clock. On the case-back is an astronaut’s footprint and the immortal words: “That’s one small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind.’ Omega will be producing 6,969 pieces. Add your name to the waiting list now.

£7,370; omegawatches.com

Grande Seconde Dual Time, Jaquet Droz

From one end of the mechanical watchmaking spectrum to the other; what Omega manufactures in a day, 40 kilometres away in a bucolic, valley-floor setting on the outskirts of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Jaquet Droz takes an entire year to produce. The boutique horologist is best known for limited-run dress watches with exquisitely-finished dials. This year’s Grande Seconde Dual Time is a case in point.

Faithful to the figure-of-eight DNA of the brand’s halo collection, the Dual Time has been updated with an azimuthal map of the Earth’s continents as viewed from the North Pole. Chapter rings around the map display the current date and the time back home. Local time is presented in a smaller dial at 12 o’clock. World-time watches have a habit of looking cluttered and chaotic. Jaquet Droz’s is a lesson is elegance – especially the example executed with a semi-precious black onyx dial.

£POA; jaquet-droz.com

Air Command, Blancpain

Not even Blancpain knows how many Air Command chronographs made it out of its Villeret headquarters during the 1950s and 60s. The brand believes around 12 prototypes found their way to America, where they were offered to pilots of the U.S. Air Force. In 2016, at an auction in Geneva, an Air Command achieved AUD 140,000. Last month, a similar model was sold at Phillips Hong Kong for £113,200.

Good news for anyone without that level of liquidity, Blancpain, which is now located in the idyllic village of Le Sentier, is reissuing the sought-after stopwatch in a 500-piece run. This year’s model takes design cues from the original prototype, which featured a black dial, luminous hour markers and a tachymeter chapter ring. Like its predecessor, the updated Air Command houses a high-precision, flyback chronograph movement, though the case has been upped to 42.5mm (from 42mm). Also new is an exhibition case-back, presenting a propeller-shaped oscillating weight in red gold.

£15,170; blancpain.com

Classique 5177 Grand Feu Blue Enamel, Breguet

Look through the transparent case-back of a mechanical wristwatch and you may just notice intricate patterns on the plates, rotor and bridges therein. The circular or straight-line markings – known formally as côtes de Genève, or Geneva stripes – are a purely decorative tradition popularised by Abraham-Louis Breguet, who began embellishing his pocket watches at the end of the 18th century (around the same time as he was busy inventing the tourbillon).

Breguet still possesses a collection of 200-year-old lathes in its L’Orient manufacture, where the brand chamfers and polishes every element of its in-houses calibres – even components you’ll never see – by hand, including the 18-kt gold rotor inside this year’s Classique 5177 Grand Feu Blue Enamel. The watch is the first Classique with a blue enamel dial, the result of buttressing several layers of enamel powder after they’ve been heated to 800 degrees Celsius. Inside the timepiece you’ll find the latest in anti-magnetic silicon technology. On the outside, hour markers that are based on calligraphy drawn by Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1787.

£18,700; breguet.com

SeaQ, Glashütte Original

It was always going to be impractical to transport watch journalists from south-west Switzerland to the home of Glashütte Original, given that the watchmaker is based in Glashütte, Germany – the clue’s in the name. Instead, Luxury London was introduced to SeaQ, the brand new dive watch from the Saxon horologist, in a sprawling convention centre next to Geneva Airport.

The brand’s first subaquatic timepiece is based on the fantastically German-sounding Spezimatic Type RP TS 200 – no, not a Terminator-style cyborg sent from the future, but a well-figured-out dive watch from 1969. (Back then the company was operating under the control of a state-owned watch consortium – which probably explains the poetic name).

The SeaQ is available in three stainless-steel versions: the entry-level, non-limited SeaQ; the 69-piece SeaQ 1969, characterised by green Super-LumiNova hands; and the slightly larger SeaQ Panorama Date, which is guaranteed to a depth of 300 metres and defined by a distinctive ‘big date’ window at 4 o’clock. All three models feature a unidirectional bezel in scratch-resistant ceramic. All look sharpest on a grey synthetic strap.

from £7,000; glashuette-original.com

Histoire de Tourbillon 10, Harry Winston

Game of Thrones take note; this is how you sign-off a series. Unveiled within the black-and-white confines of Harry Winston’s Geneva-based manufacture, the 10th and final chapter in the brand’s Histoire de Tourbillon series is full-on theatrics. Four tourbillons with four separate balances (a world first), three differentials and two mainsprings regulate the hour and minute hand on a raised, centralised sub-dial (curiously, there is a no second hand). The rectangular timepiece – which measures a whopping 53.30mm x 39.10mm x 17.60mm – is topped with a colossal sapphire-crystal case and, all told, comprises 673 components.

Three editions are being produced; 10 pieces in white gold, 10 pieces in rose gold and a one-of-a-kind model in ‘Winstonium’ (platinum in English), which is characterised by its melodramatic blued tourbillon bridges (seen here). The aim of the Histoire de Tourbillon series was to present the gyrating tourbillon as the most aesthetically arresting complication in watchmaking. Mission accomplished.

from CHF700,000 (approx. £565,750); harrywinston.com