Serena Williams’ coach Patrick Mouratoglou has invented a new type of tennis

“Even professional tennis players don’t watch tennis matches. They just watch the highlights.”

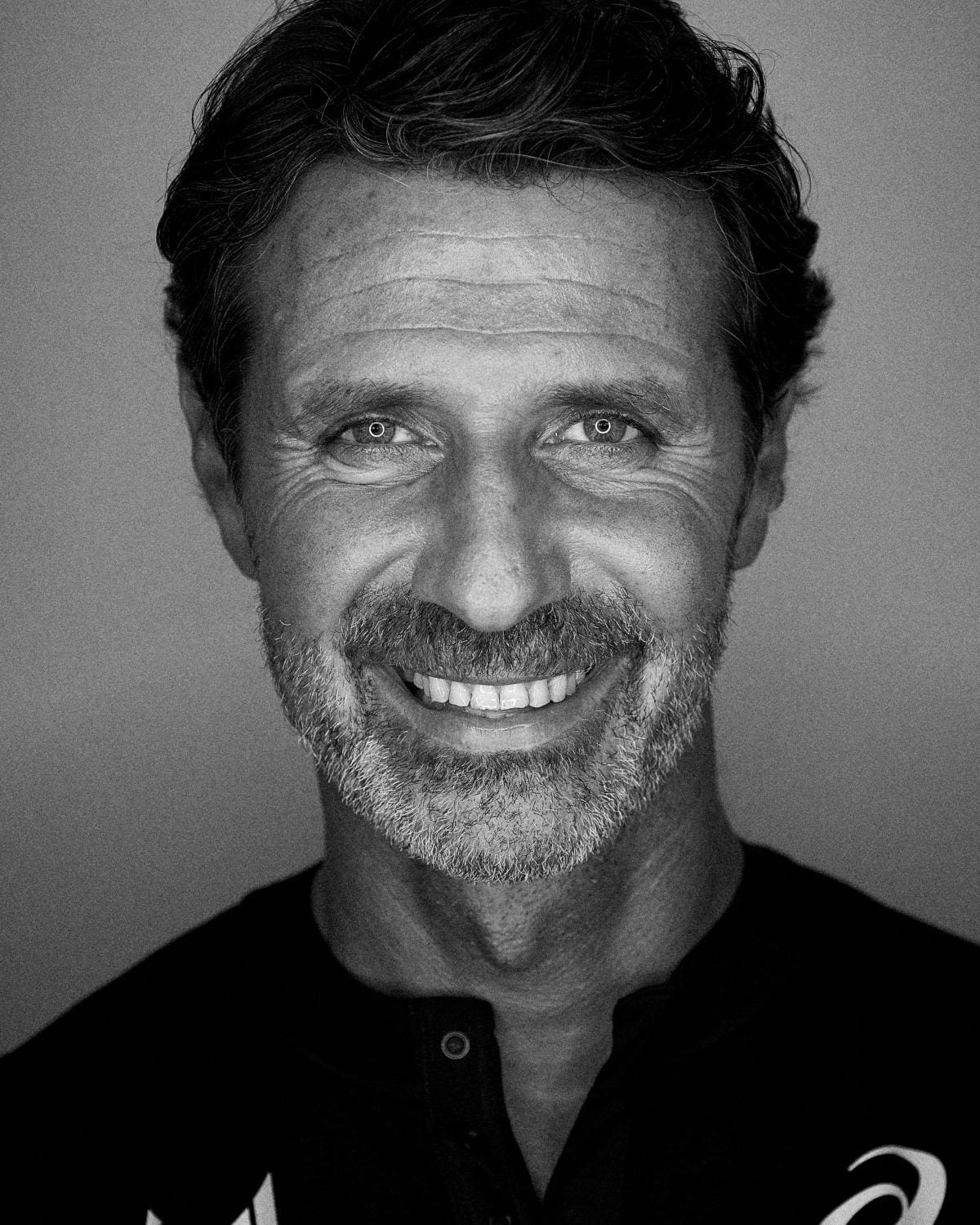

I’m really sorry, I have to go,” says Patrick Mouratoglou. “Serena has decided she wants to practice, so I need to get to the courts.” And, with that, the world’s leading tennis coach is off. Mouratoglou, for the uninitiated, is the super tutor who guided Serena Williams to becoming the most decorated women’s tennis player in Grand Slam history. He’s also the coach of Greece’s Stefanos Tsitsipas, who recently came within a racquet string’s breadth of beating world number one Novak Djokovic in the final of the French Open.

“When it comes to selecting the players I work with,” says Mouratoglou – he’s so effective that top players come to him – “I’m looking for those who can win Grand Slams, and for that you have to be extremely competitive, have high goals, believe in your potential and be dedicated to work. I can improve every aspect of a player’s game, but I can’t give an unconfident person the confidence to go all the way. At this level, players have a very deep conviction that they can win.”

Winning matters most, of course. “I once heard Arsene Wenger asked how he managed to stay manager of Arsenal Football Club for 20 years,” says Mouratoglou. “He said [it was] because the team had never lost three matches in a row. And it’s the same in tennis – you lose and you’re out. Most coaches last about a year with a top player.”

It says much, then, that Williams, for example, has been with Mouratoglou for almost a decade. In tennis, like most single-competitor racquet sports, it takes two to win: player and coach. And that combination has to be right. Mouratoglou recalls a time when he was introduced to a promising young 10-year-old. He spent some time chatting to him about his game, about what he wanted out of tennis, and that was enough to convince Mouratoglou to take him on.

“They asked if I wanted to see him play and I said that it wasn’t necessary. I mean, it was a given that he could play. What I needed to know was who he was and how he thought.”

Small surprise that Mouratoglou sees himself as much a psychologist as a strategist and technician. “Of course, a good coach needs all those tools, and doesn’t know when he’ll have to apply which tool until the moment comes,” he says. “But they all connect, and really this is about a player’s mentality.”

Mouratoglou says the difference between coach and player is akin to that between an actor and a director. And, indeed, he’s been vocal as to tennis’ habit of finding coaches in ex-players – who often turn out not to be very good. “The danger then is that the player just wants to coach in the way he was coached, and as a result, nothing changes.”

Mouratoglou was a promising youth player himself, before he was persuaded away from the sport and into the family business. Eventually, though, he realised that his relationship with tennis was an obsession. And so, he apologised to his parents and created his own coaching academy. “My approach to coaching has always been about differentiating, about tailoring coaching to each player. It’s why with the academies we go out of our way to recruit younger coaches, so they’re not already fixed on one way of working with all players. That standardised model doesn’t work.”

Naturally, the traditional coaching world thought he was crazy, not least because Mouratoglou was still in his 20s at the time. But how his business has grown. As well as his HQ in the south of France, there’s now a Mouratoglou tennis centre in Dubai and, just opened, one in Costa Navarino, which boasts Greece’s first, and only, grass court. There are several Mouratoglou tennis programmes at luxury hotels around the world, with a rollout to other hotels in the pipeline.

All of which might suggest that tennis is in a healthy place. Yet Mouratoglou isn’t so sure. He’s become something of a vocal critic of its various problems. Why, he asks, does all the money in professional tennis pool at the top? This being a situation, of course, that suits his own bank balance just fine.

“It’s absolutely not normal in a global sport, with a lot of money in it, that a player ranked, say, 120 in the world can’t make a decent living, when the 120th best football player, just in the UK, will earn 10 times more. We have to look at the way winnings are distributed.”

Mouratoglou also points to the fact that the typical age of people following tennis, or playing at club level, now starts with a six, with the number that follows it slowly creeping up year on year. Tennis has little long-term future, he believes, unless it can get young people more interested in the sport.

In part, this is a product of the digital age: not just that there are other things to watch, but that a younger audience is used to more dynamic, immersive, pacey entertainment. A tennis match, in contrast, can last hours “and most of that time is watching players do their routines, bouncing the ball 200 times before serving,” says Mouratoglou. “Even professional tennis players don’t watch tennis matches. They just watch the highlights.”

It’s also a product of changes made by the tennis authorities over recent decades, suggests Mouratoglou, not least a tighter code of conduct “that can make players feel like they’re being told off at school”. Tennis tamps down the personalities that made the sport so watchable in its 70s and 80s heyday – the era of ‘Ice Man’ Björn Borg and ‘Wild Man’ John McEnroe.

Witness, perhaps, the (mostly) positive reaction to Naomi Osaka after she withdrew from the French Open having been fined $15,000 for her decision not to take part in those interminably boring post-match interviews. Citing the impact that such mandatory media activities had on her mental health, Osaka was widely applauded for her renegade spirit – and for shining a light on the off-court pressures tennis players are put under.

“In other sports, even team sports, you know who’s who. And you see passion play out on the field,” says Mouratoglou, who has asked, rhetorically, what difference it makes to anyone if, for example, a player wants to smash their own racket in frustration. “Yet tennis players all have to pretend they’re very nice, all very friendly. It just doesn’t feel authentic anymore.”

So, Mouratoglou has recently proposed a different kind of tennis. Calling it the Ultimate Tennis Showdown, he’s brought top-flight pros together to play matches in four quarters of 10-minute segments; there are wild cards – a player may have only one serve, for example, or may have to play their winning shot within three strokes; viewers are privy to pep talks between the players and their coaches between segments; and low camera angles show just how fast the ball is moving. Compared with most tennis matches, it’s fun and very fast.

“Of course, plenty of people said ‘it will never take off’,” says Mouratoglou, adding that UTS draws top-five players and that its Facebook page, where the matches are shown, currently has 600,000 members. “But it’s all about how you present it. There will always be people against novelty and change, so I’m not worried about that. Besides, this isn’t instead of traditional tennis, which I love, but which just isn’t modern – this is about doing something completely different in order to grow the whole pie. It’s remembering that all professional sport exists for one reason – because people watch it.”

The Ultimate Tennis Showdown is not for the purists, Mouratoglou concedes, but as someone who loves the sport, he’s all out to convince people that it has to evolve rapidly if it wants to keep growing. Otherwise, he argues, the sport’s inherent conservatism will see it become senescent.

“I regretted not continuing as a player when I was young and it took me 10 years to get over it,” says Mouratoglou. “But that convinced me that when you don’t convince other people you perhaps don’t get to live the life you want – and I didn’t convince my parents that I should pursue tennis as a player. You have to carry people with you.

“I’m fine about it now,” Mouratoglou chuckles. “After all, how many people can say they work in something they’re passionate about, that they spend their time helping people achieve their potential? I really am very lucky indeed.”

Read more: Lewis Hamilton on driving diversity in motorsport

For the Ultimate Tennis Showdown calendar and to watch live, visit utslive.tv