Notting Hill Carnival: The history, the highlights and what it means to so many

For millions of Londoners, the August Bank Holiday is about just one thing: the glorious, colourful event that is Carnival, with its rich cultural and musical history

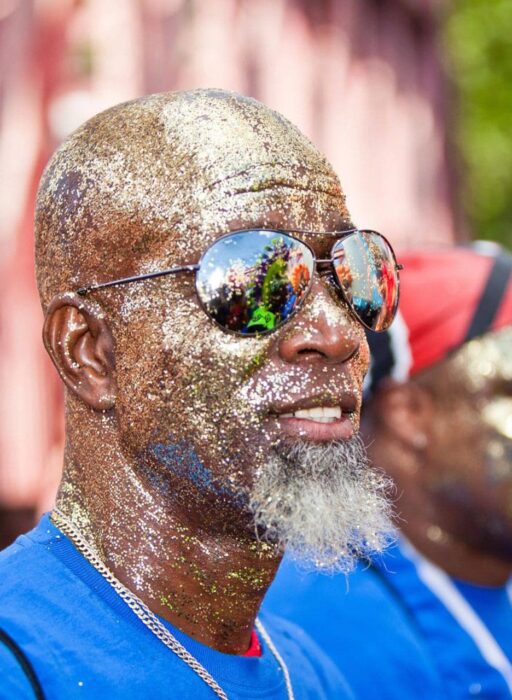

Notting Hill Carnival is returning to West London this weekend as Europe’s biggest street festival. With thousands of participants, millions of spectators and a parade that winds its way through Notting Hill, Ladbroke Grove, Westbourne Grove, Westbourne Park and Kensal Rise, this year’s celebration of Caribbean culture will take place from 26-28 August bringing plenty of vibrant costumes, music and food with it.

The history of this event – an annual highlight for so many and renowned worldwide for its cultural importance as much as its scale – is complex. “Where did the Caribbean Carnival in Notting Hill come from?” wrote activist, author, researcher and lecturer Michael La Rose in 2004 in 40 Years of the Notting Hill Carnival. “The answer is in the mass migration of people from all over the Caribbean to England in the 1950s. They came to make a better life and to answer the call of Britain’s economy that was desperate for workers after the ravages of the Second World War. We came on invitation, we were recruited.

“This fearless Caribbean generation brought with them in their heads the fantasy of the Caribbean mas (masquerade) tradition, in their hands the steelpan beating art, in their blood the pulsating Caribbean rhythms and dance, on their lips the calypso and in their hearts and souls the organisation, commitment and love for Caribbean Carnival culture.”

In these words, the passion for Notting Hill Carnival’s (NHC) shared sounds, sights and traditions is palpable – they are the reason for its foundation, for its ongoing success and why it will continue for generations to come. Some of the most iconic images of events past and present are of the mas bands, dressed in incredible costumes and assessed by official judges on both days of Carnival. The origins of mas, from ‘masquerade’, go back to the 1800s with the emancipation of slavery in the Caribbean.

“Prior to their freedom,” the NHC website explains, “the slaves would mimic and ridicule the masters, copying the elaborate gowns worn at their celebration balls and combining them with many African traditions of their former cultures – which included costumes made with bones and natural products, and blue devils playing music with tins and bamboo. Once the slaves were freed from the French, Spanish and English, they would openly continue and elaborate on these foundations, so the Caribbean carnival developed as a fusion of African and European traditions and culture.”

The roots of NHC itself were put down at a time when many people had left the Caribbean for a new life in Britain as part of the Windrush Generation. In 1959, Trinidadian community activist Claudia Jones recognised that something should be done to unite her local community in response to the troubling state of race relations; the UK’s first widespread racial attacks, the Notting Hill race riots, had occurred the previous year. She held her first of several indoor Caribbean Carnivals that year at St Pancras Town Hall; La Rose points out that Jones “understood the artistry and creativity of the Caribbean Carnival. She understood the unifying power of Carnival. She felt that it was important to build on the unity of Caribbean people forged in the fight back during the race riots”.

Linett Kamala, a member of the NHC Board of Directors, was born to Jamaican parents who lived in the Notting Hill area when they first arrived in the UK in the 1950s. She became one of the first female DJs at Carnival at the age of 15 and now, 37 years later, she is the manager of the same static sound system at which she first performed, Disya Jeneration; music has always been central to NHC. In 1964, Russell Henderson, an established pianist from Trinidad, was invited by Laslett to play steel drums at her annual event on Tavistock Road in W11. The public, delighted by the small parade, joined in with the impromptu street party.

The Carnival team cites this moment as “the spark that gave Laslett the idea to apply to the local council for permission to have an outdoor event; she saw the impact the steel pan had in uniting the local community and hoped she could replicate this by encouraging the small communities of a very multicultural West London at the time to take part by infecting ‘them with a desire to participate’, stating ‘this can only have good results’.” The Notting Hill Fayre and Pageant was held over the course of a week from 18 September 1966.

Steelpan remains an integral element of NHC today; it is one of the key events for the best pan players and steel pan bands from all over the UK to showcase their skills. It takes year-round, and even lifelong dedication to master it. One of Europe’s top Soca artists and Carnival ambassador Triniboi Joocie explains why Notting Hill Carnival is unique when it comes to its music: “In the Caribbean the music played in Carnival is predominantly Soca and Calypso whereas in NHC they have allowed other genres of music to be heard such as Afrobeats, Reggae and Dubstep. This I believe broadens the marketing of the carnival, allowing new audiences to attend each year.”

Carnival has weathered storms of controversy over the decades, fighting back over press coverage that often took an unfairly negative and one-sided view of the event, and standing up to people who wanted it to be banned. In 1976 and several subsequent years, NHC was marred by riots; King Charles was one of the few establishment figures who supported its continuation. It has also attracted criticism for the cost of policing the event, although many then point out what NHC adds to the local economy outweighs these costs. By and large, the positivity surrounding NHC shines through and continue it does, growing, thriving and evolving into the event it is today.

Food is a vital part of proceedings – you won’t go hungry as you sample food from one of hundreds of stalls, selling Jamaican jerk chicken and Trinidadian roti and Guyanese pepperpot – as are the remarkable mas costumes, bold and dynamic with lots of movement and detail. And they are officially art: by 1980, the Arts Council had fully recognised mas as an art form. Claire Holder, the longest serving Chair of the Carnival committee from 1989 to 2002, instituted appearance fees and prizes for the mas bands as well as securing significant sponsorship for the carnival as a whole. This was important for the bands, both in terms of recognition of the art form and in giving them opportunities for development.

NHC’s Advisory Council today includes cultural and political activist Ansel Wong, impresario Sonny Blacks, steelpan arranger and soloist Debra Eden and Soca News’ Katie Segal. Wong declares that today’s Carnival is “different” from those of years gone by, “but just as enjoyable. Just as memorable”. Blacks has been involved since the very earliest days; he convened the first group that organised the earliest Carnivals in Notting Hill Gate and has always been involved in the arts and culture of Trinidad, especially Carnival, Calypso and Steel Pan.

Eden too was involved in Carnival from an early age, in mas bands and as a pan player: “My focus now,” she says, “is the evolution of carnival arts”. Segal shares her wish to “nurture what we already have, and encourage it to… grow in positive directions. It’s clear to me that involving and educating children and young people is the only way to ensure a successful future”.

Notting Hill Carnival 2023 runs from Saturday 26 August until Monday 28 August, visit nhcarnival.org

Read more: Bank holiday breaks in the UK: Where to stay, eat and what to do