The Rossettis: Europe’s most culturally influential family – and their lost muses

A new Tate Britain exhibition will explore the substantial contribution of one family to the arts in Britain. But their journey to notoriety was fraught, and littered with collateral damage…

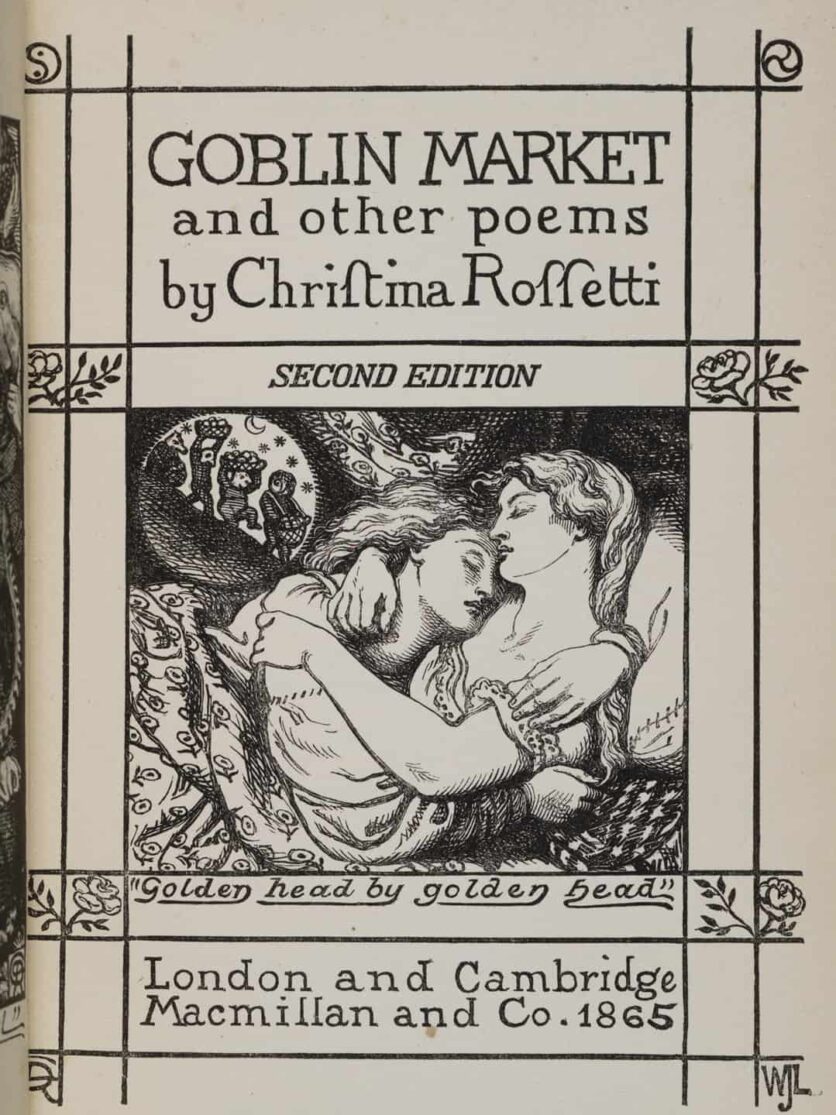

Siblings Maria, Dante Gabriel, William and Christina Rossetti had the arts running through their veins; all became either poets, authors, illustrators, painters or critics. The two with the most enduring legacies, however, are Christina, who penned poems such as Goblin Market and In The Bleak Midwinter, and Dante Gabriel, a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelites. Their extensive contribution to art and literature is traced in a new exhibition, The Rossettis, opening at Tate Britain today.

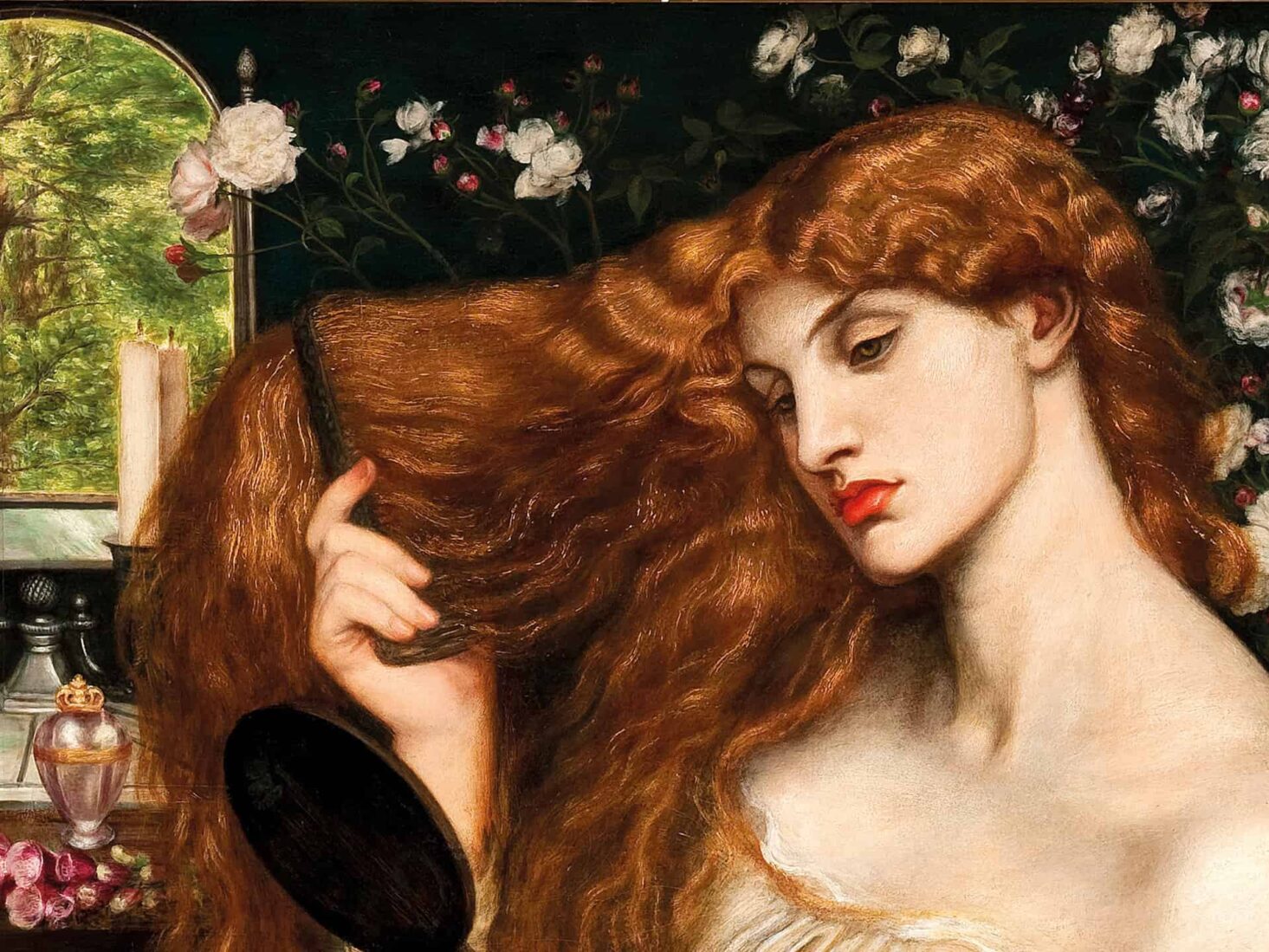

A beloved Christmas carol and lurid images of luscious-lipped beauties were only the tip of the iceberg, however. Behind the scenes, the lives of the Rossettis were complex – Dante Gabriel was a philanderer who became obsessed with the women who modelled for him. Christina, meanwhile, had her brother’s number, accusing him of idealising the women (who she called “nameless girl[s]”) until “every canvas means/the one same meaning”. Perhaps her own refusal to marry reflected a desire to distinguish herself in her own right, and to avoid a legacy stripped of agency, as seems to be the fate of the Pre-Raphaelite muse.

The oldest Rossetti brother helped found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. The PRB, as it came to be known, was fascinated by Medieval art, and sought to reinstate the colours and compositions of the era. The second tenet of the movement was realism – it rejected the approach of Mannerist art (which succeeded Raphael, hence ‘Pre-Raphaelite’), which possessed qualities of exaggerated or unnatural perfection.

Although the visual appeal of Pre-Raphaelite art cannot be disputed, there does exist a question over just how ‘revolutionary’ the Brotherhood was. Dante Gabriel’s paintings did, after a while, seem to simply focus on beautiful women.

So, who were the women behind these paintings? Let’s begin with his wife, Elizabeth Siddal. In the winter of 1849, Dante Gabriel was painting when his friend burst into the studio, announcing, “You fellows can’t tell what a stupendously beautiful creature I have found… She’s like a queen.” Siddall began working as a model for the PRB and was most famously immortalised in John Millais’ Ophelia. She met Dante Gabriel in 1850 and became his muse and lover.

Although Siddal is remembered primarily as a model, she had a painting career of her own (The Rossettis, in fact, will include the first retrospective of her work). In her own self-portrait, she depicts herself looking harsher, angrier and less attractive than the languid Siddal of the Pre-Raphaelite paintings. It is a rare (and welcome) glimpse into how she perceived herself, when so much of her image has been controlled by others.

Although Siddal’s work was decidedly less refined than the PRB’s (it’s important to remember that she had a fraction of the time and resources invested in her career as did Dante Gabriel et al), John Ruskin still declared her a “genius”, providing her with an annual salary of £150 (around £25,800 in today’s money) to paint.

However, Siddall had fallen curse of the moniker of muse, and this was destined to be her lot, both in life and posterity, despite her best efforts to escape it – she gave up Ruskin’s stipend, wishing to be rid of his influence, instead enrolling at the Sheffield School of Art. But then, in 1860, Siddal became dangerously ill; Dante Gabriel rushed to be with her, and they were married soon after. Siddal became pregnant, and that was the beginning of the end of her fledgling career.

Siddal was addicted to laudanum, which was perhaps why, in 1861, she gave birth to a stillborn daughter. Siddal never recovered from the loss and, on a February evening the following year, Dante Gabriel returned from a night class to find that she had died by suicide.

Siddal was the epitome of Christina’s “nameless girl”. Although Dante Gabriel and his peers revered her – obsessed over her even (he kept a lock of her hair, which is exhibited in the Tate exhibition) – did they really recognise her value beyond her looks? When she posed for Ophelia, Millais had her lie in a bath for hours on end, and she caught pneumonia. After Siddal began modelling for Dante Gabriel, he jealously forbade her from sitting for anyone else. To them, she was a commodity.

There is a macabre postscript to Siddal’s life: Dante Gabriel buried her with some of his poems which, years later, he decided he wanted back. In 1869, her coffin was exhumed from Highgate Cemetery; it was said that Siddal’s body was perfectly preserved, though her hair had grown to fill the entire coffin. Even in death, she was idealised and sentimentalised by men.

Another woman who regularly appears in Dante Gabriel’s paintings is Jane Morris. In 1857, Morris (or Burden, as she was called then), was noticed by Dante Gabriel at a play. He asked her to model for him, and she later sat for William Morris, who fell in love with her. They became engaged, although by Morris’ own admission she was not in love with William. Instead, she became attached to Dante Gabriel, and the pair started a long-lasting affair.

Morris, like Siddal, “consumed and obsessed [Dante Gabriel] in paint, poetry, and life”. But, also like Siddal, she was talented in her own right, and in a way that has been obscured by her proximity to male ‘greatness’. She was lower-class and uneducated, but took to being a gentleman’s wife like a duck to water. She became proficient in French and Italian, an accomplished pianist, and is rumoured to have inspired Eliza Doolittle in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion.

Morris also became a skilled embroiderer, and is said to have had more than a hand in the success of her husband’s now world-famous designs. Despite the fact that Morris was a key player, credit was given to William “in the interests of commercial success”. It’s likely that Morris’ contributions have been minimised in part due to a certain amount of prurience surrounding the fact that she was notoriously unfaithful to her husband – the wealthy, middle-class lion of the British art scene.

There were more muses and more affairs; Fanny Cornforth, like the others, was of a lower-class background and ‘adopted’ by the Brotherhood. Ditto Alexa Wilding, whose career as an actress was cut short when Dante Gabriel literally jumped out of a cab to drag her to his studio. It is Wilding’s face in Dante Gabriel’s sexiest work, Venus Verticordia – but Cornforth’s body. She suffered the mortification of posing for the painting, only for her face to be replaced with Wilding’s.

Cornforth’s story has a tragic end. She outlived Dante Gabriel, as well as the husband that she married afterward, and was put in the workhouse by her sister-in-law when she developed dementia. Cornforth was moved to the West Sussex County Lunatic Asylum in 1907 and remained here until her death when she was buried in a common grave.

So, perhaps it’s not altogether surprising that Christina wanted more from her life than being a prop. The youngest Rossetti was brought up on Dante Alighieri and Petrarch, and regularly visited Madame Tussauds, London Zoo and the newly opened Regent’s Park. She soaked it up like a sponge, dictating her first story to her mother before she had learned how to write.

But her intellectually stimulating childhood was short-lived; in the 1840s, the Rossettis fell on hard times. Maria became a live-in governess – a prospect that Christina dreaded, and she suffered a nervous breakdown at 14. In her late teens, she became engaged to James Collinson, a member of the PRB, but ended the relationship when he reverted to Catholicism. She would later become involved with a linguist and another painter, both of whom she refused on similar grounds.

In her poem In An Artist’s Studio, Christina describes a model whose “face looks out from all his canvases” – a “nameless girl” whose visage the artist “feeds upon… by day and night”. Had she married a painter, she may have acquiesced to having her face “fed upon” – and she came close, posing for a number of Dante Gabriel’s paintings. However, the fate of Siddall and Morris – of being eclipsed by their role as muses and lovers – was not to befall Christina. Her first commercial collection, Goblin Market and Other Poems, was released in 1862 to great critical acclaim, with many naming her as the natural successor to Elizabeth Barratt Browning.

The titular poem has been widely interpreted as a critique of Victorian gender roles – however, it’s important that we do not mould Christina to fit an overly convenient narrative as the down-to-earth foil to Dante Gabriel’s hubris and misogyny. She was ambivalent about women’s suffrage, and Goblin Market can also be said to be about temptation and salvation, or a study of erotic desire and social redemption. Her remarks in The Artist’s Studio, meanwhile, may have been more about male artists’ self-obsession than the ‘male gaze’, which was not a known concept at the time.

Either way, Christina courted professional success up until her death in 1894. As for Dante Gabriel, he became a morbid character towards the end of his life, adopting eccentric habits while holed up in his Cheyne Walk house. He was obsessed with exotic animals, buying a pet wombat, llama and toucan, which he dressed in a cowboy hat and trained to ride on the llama’s back.

Dante Gabriel was addicted to chloral hydrate, and this began to take a toll on his mental and physical health. He also began suffering from alcohol psychosis brought on by the whisky that he used to drown out the taste of the drug. He died in 1882.

Modern art and literature owes a lot to the Rossettis, but perhaps the most important lesson that we can take from their lives is the uphill battle women have waged, and still must wage, for independence and success, and that behind many a male ‘genius’ is a forgotten woman – or four.

The Rossettis runs from 6 April – 24 September 2023, visit tate.org.uk