Peggy Guggenheim, Venice and London’s ‘lost’ gallery

As Venice’s Guggenheim Collection celebrates its 75th anniversary, we delve into the life of its pioneering founder – and her London gallery that never was

75 years ago, the neglected garden of a squat, semi-ruined ‘palazzo’ on the banks of Venice’s Grand Canal opened its gates to visitors for the first time in years as the Peggy Guggenheim Collection newly-christened. Only one-storey high, original plans for the building were intended for it to dwarf the array of 13th and 14th century churches and merchant houses on the waterfront.

Unfinished by its original owners, the palazzo and its garden, where guests could now observe a collection of sculptures by the likes of Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti, had gained a mysterious reputation as a den of decadent parties in the second decade of the 20th century – all hosted by Luisa Casati, a Milanese marchesa who kept a pet cheetah and walked through San Marco square dressed in nothing but a fur coat.

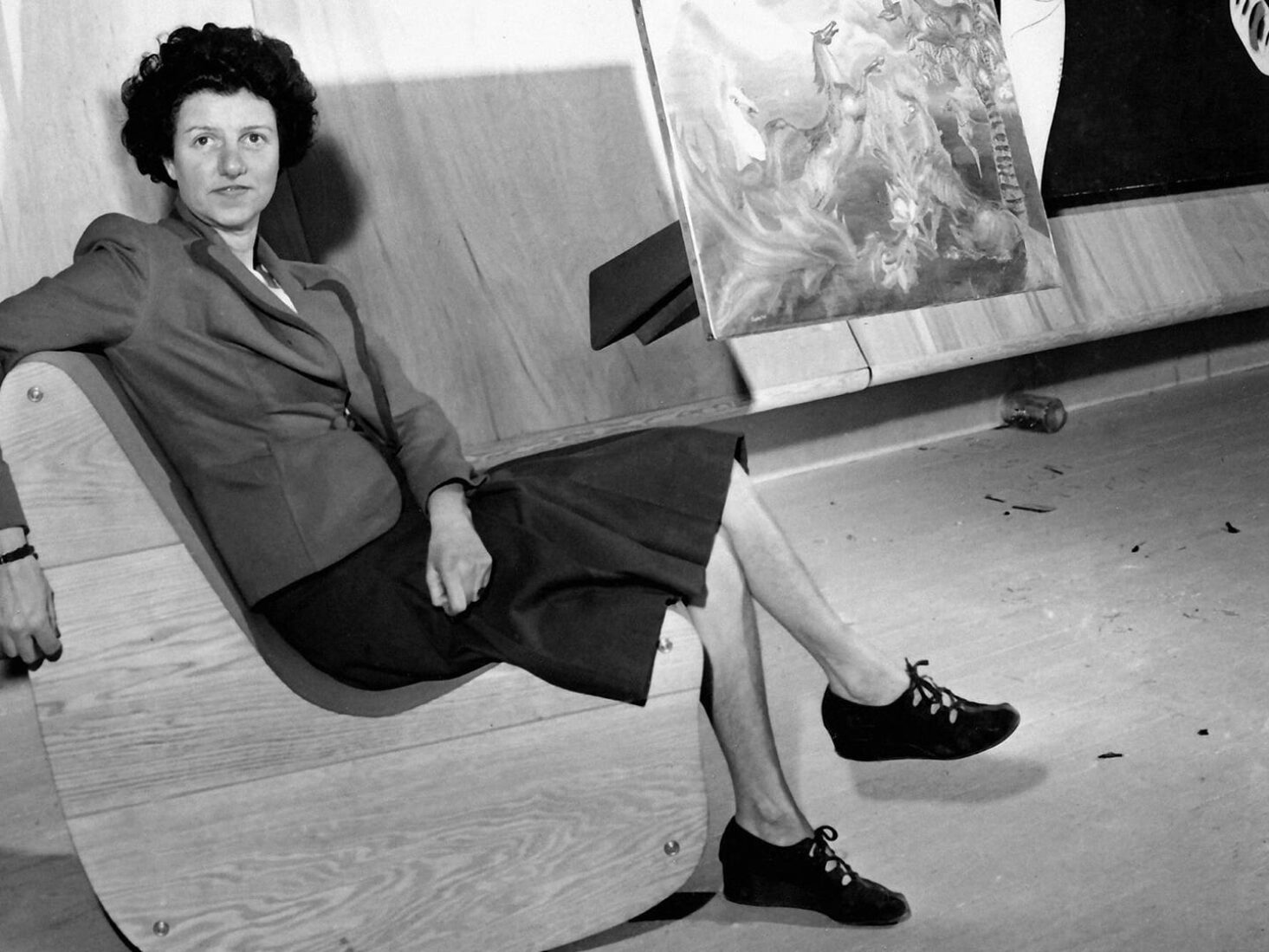

The new occupant of what was, at that time, known as the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni was Peggy Guggenheim; the industrious and highly unconventional scion of the American familial dynasty that made its fortune from lead, copper and silver. Guggenheim first visited Venice in 1924 with her husband Laurence Vail. Their marriage was crumbling but Guggenheim was entranced by the city, later writing that it was a place ‘sprung from the sea’ where ‘no time exists’.

Today, her Venice museum receives close to half a million visitors a year, all paying due reverence to a collection that includes works by Man Ray, Bacon, Dali, Duchamp, Cocteau, Pollock and Picasso. Yet, her arrival in Italy in 1948, and her transformation of the Venier palazzo into the Guggenheim Collection the following year, came about only because of events in the city where Guggenheim initially wanted her collection to reside: London.

For 18 months, until the outbreak of the Second World War, Guggenheim, then only in her late 30s, ran a commercial gallery called Guggenheim Jeune on Cork Street in Mayfair. Her reputation as a vivacious and financially generous supporter of modern art and avant-garde artists and writers was solidified by her willingness to buy or display artworks that other, more staid galleries wouldn’t touch – and by her ability to find inventive ways to ensure the public could see them.

Banned from displaying Jean Cocteau’s La peur donnant des ailes au courage (‘Fear Gives Wings To Courage’) on the gallery walls in Cork Street, due to its graphic depictions of pubic hair, Guggenheim came up with an alternative. If a gallery visitor asked permission to visit her office they would be able to see the shocking portrayal of bandaged and bloodied lovers – hung above her desk.

Cocteau was said to have used his own blood in this visual testament to his support for the doomed Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. Its unusual new home in a Mayfair back office gave Guggenheim’s nascent gallery a critically-lauded reputation (if not the profits needed to make it sustainable).

It could never be said of Guggenheim that she had a natural intellect about modern art – she once admitted to having to visit Marcel Duchamp in order to ask him personally what the difference was between abstract and surrealist art. But her deep (though not nearly as deep as other members of her family) pockets, alluring personality and work ethic (new shows at Guggenheim Jeune were launched every four weeks) meant that artists flocked to her humble gallery. One of these neophytes was a 15-year-old Lucian Freud, whose earliest work was displayed by Guggenheim as part of a group show titled An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Children.

However, if the attitude of avant-garde artists and critics towards Guggenheim’s gallery was encouraging in 1938, the same could not be said of the loftier echelons of the London’s art establishment. Just a few months after opening Jeune, Guggenheim attempted to import sculptures by Henry Moore, Alexander Calder and Constantin Brancusi for display in Cork Street. But, to avoid paying import duties, Guggenheim needed to ensure that the pieces were officially sanctioned as artworks. For this she needed the cooperation of a more seasoned art collection and so she asked the director of the Tate to vouchsafe for the artistic merit of the pieces.

The Tate, however, refused to acknowledge that the works had any artistic value whatsoever. Ticking the box marked ‘non-art’ meant that the sculptures were defined as ‘manufactured goods’. An incredulous Guggenheim took the case to Parliament, arguing, successfully, that modern art needed to be recognised and appreciated on the same level as any Tintoretto or Titian. It’s a move the Tate would come to rue: despite future charm offences towards her in the 1960s, it never managed to purchase any of Guggenheim’s collection.

Despite successful shows by Wassily Kandinsky, Yves Tanguy and John Tunnard, Guggenheim Jeune shut down in June 1939. Guggenheim claimed afterwards that the gallery ‘proved to be too expensive for what it was’, a conclusion perhaps drawn partially by the fact that Guggenheim had bought so many of the exhibited artworks herself during the Jeune’s brief tenure.

Thinking that it would be better to lose her money in style rather than have failure drip-fed to her, Guggenheim went for broke and decided that, rather than persevere with her small, commercial gallery, she should devote herself to giving London its first modern art museum. In a letter to her friend, the American writer Emily Coleman, Guggenheim wrote: 'It is very brave and idiotic to start a museum with so little money. But we hope lots of people will come to our rescue. They have already promised… I hope you will come back and see it all before Mr. Hitler drops his bomb on it.’

"To live in Venice or even to visit it means that you fall in love with the city itself."

Peggy Guggenheim

Devised with the help of the art journalist Herbert Read, who was to act as the museum’s director, an offer was made by Kenneth Clarke (who would go on to write and present the seminal BBC art history series Civilisation) to use his townhouse near Broadcasting House as the museum’s home. But Clarke’s residence was only available because its owner knew war was coming; before long Clarke’s departure was swiftly followed by Guggenheim and her young children, who took refuge in Paris.

‘I soon gave up the idea of going back to England,’ Guggenheim later wrote. ‘I therefore had to relinquish the museum, which would have been impossible anyhow since we could not have borrowed paintings and exposed them to the bombings of London.’

During her brief stay in Paris, echoes of the treatment Guggenheim received at the hands of the Tate became apparent when she asked the Louvre to securely store her collection, which by now included works by Braque, Mondrian and Kandinsky. Once again, the gallery chieftains considered the modern art pieces not worth saving. Ironically, it was only by describing them as being ‘non-art’ pieces, just as the Tate had earlier dismissed them, that Guggenheim was able to get her collection back to New York, labelling them ‘Household Items’ when they were shipped across the Atlantic in 1941.

It was in Manhattan that Guggenheim’s dreams for a modern art museum were finally realised, in the form of the Art of This Century space on West 57th Street, before she found her home on the banks of the Venetian lagoon in the years immediately after WWII. History records that it was war alone that prevented London from becoming the cynosure of the Guggenheim Collection. Yet, were it not for the sniffy reaction of the art establishment to Guggenheim’s adoration of contemporary art, could it have been possible for Guggenheim to store her nascent collection somewhere in the UK far from London until the end of the war, when her modern art museum in the capital could be realised?

London’s loss has been Venice’s gain for three quarters of a century now. Once her Venetian palazzo had been established as a gallery, it seems Guggenheim rarely thought of Britain again. For her, there was simply no comparison between trawlers on the Thames and gondolas gliding past ducal palaces. As Guggenheim later wrote of Venice, ‘There is nothing left over in your heart for anyone else. To live in Venice or even to visit it means that you fall in love with the city itself.’

Cork Street, despite its quirky charms, could frankly never compete.

For more on the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and its upcoming Jean Cocteau exhibition visit guggenheim-venice.it.

Read more: Yoko Ono and the making of the controversial Film No. 4