Pablo Picasso’s women: uncovering the muses behind the artist’s pre-eminent portraits

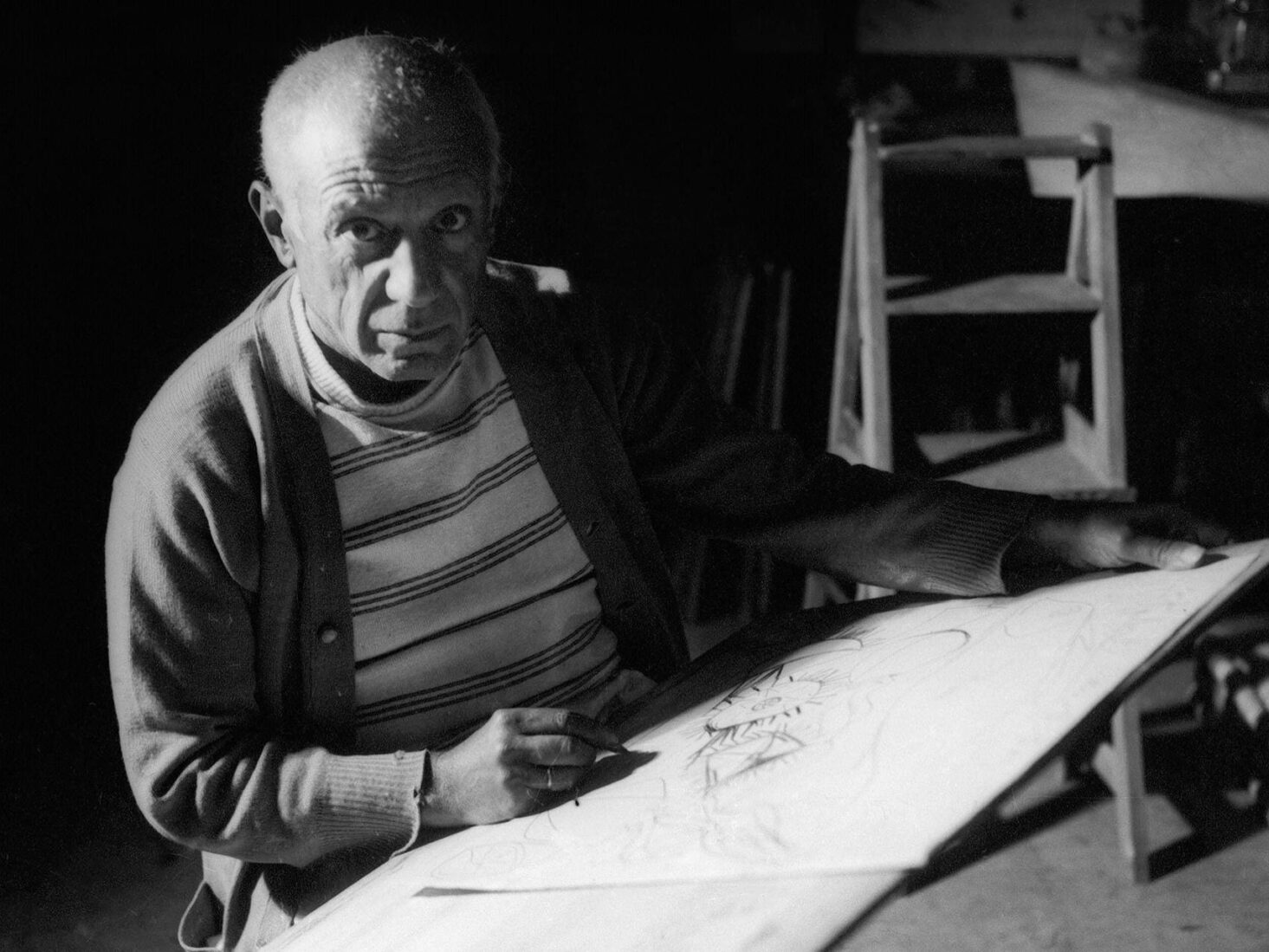

Behind every great man are six great women – or at least there were for Pablo Picasso. As a new exhibition opens at the Royal Academy in London, we explore how the prolific womaniser took his

“For me, there are only two types of women: goddesses and doormats,” Pablo Picasso told his mistress Françoise Gilot in 1943, as the couple began their 10-year affair. It was a warning and it wasn’t Gilot’s first – a friend had already told her she was heading down a straight path to catastrophe. “I told her she was probably right, but I felt it was the kind of catastrophe I didn’t want to avoid,” the painter wrote in her 1964 memoir Life With Picasso. A decade was enough. In 1953, she left him – the only one of ‘his’ women who ever did.

A serial philanderer, Picasso’s creativity seems tied to his adultery. While his affairs were innumerable, six women in particular are credited as catalysts for his artistic development, each providing inspiration for a different period of his life. Their influence came at great personal cost; of these six women, two killed themselves and two suffered severe mental illness.

“He submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them, and crushed them onto his canvas,” the artist’s granddaughter, Marina Picasso, wrote in her 2001 memoir Picasso: My Grandfather. “After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.”

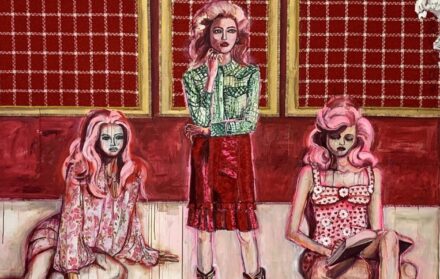

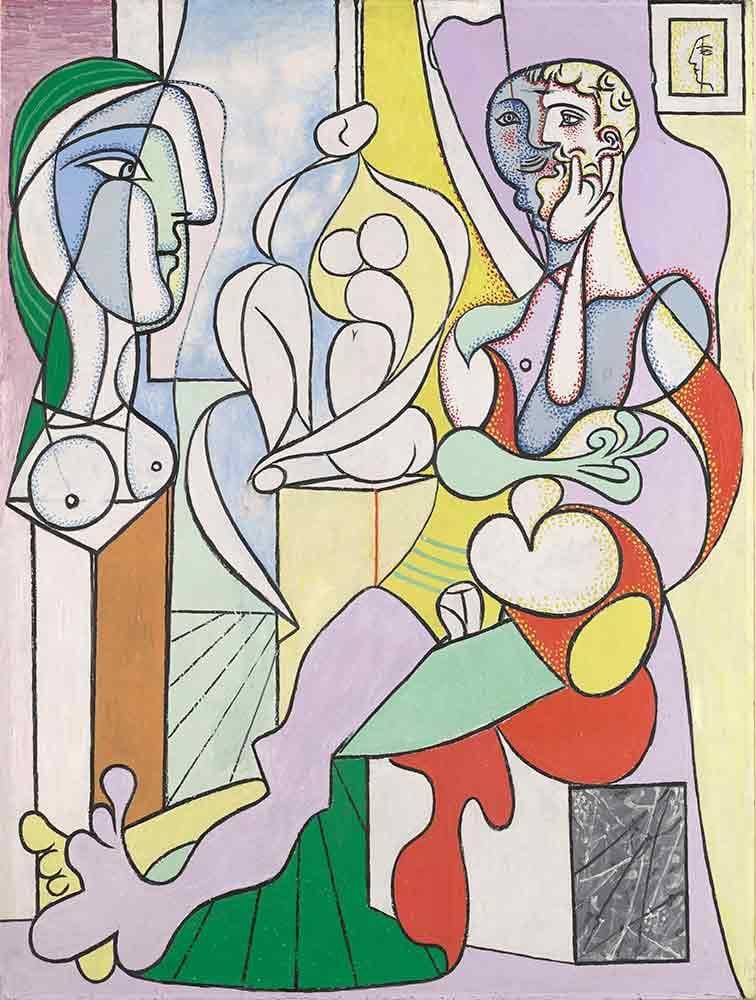

Venerated today as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, Picasso’s turbulent relationships are woven into his works. Subjects once painted with tenderness later appear torn apart, rehashed as cubist creations and, in some cases, melded with other women as they overlapped in real life.

“It must be painful, Picasso would say with more pride than guilt, for a woman to watch herself transformed into a monster, or fade from his work, while a new favourite materializes in all her glory,” wrote the artist’s friend, the late Sir John Richardson in A Life of Picasso. Based on this biography, the new book Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline (£77, www.gagosianshop.com) reproduces 36 artworks that depict the six muses who played a prominent role in both the artist’s life and work – intertwined as they were.

First was Fernande Olivier. They met in 1904 when she was a model and he a burgeoning artist yet to find fame. Jealousy ripped through the relationship, and he forbade her from sitting for other artists. She posed for more than 60 of Picasso’s portraits and inspired several of his early Cubist works. Mutual infidelity saw the relationship come to an end in 1912, although bad blood remained between them. At the peak of Picasso’s success, Olivier sold a tell-all, serialised story to the Belgian newspaper Le Soir, which the artist’s lawyers halted six issues in. The full version wasn’t published until 1988, after both parties had died.

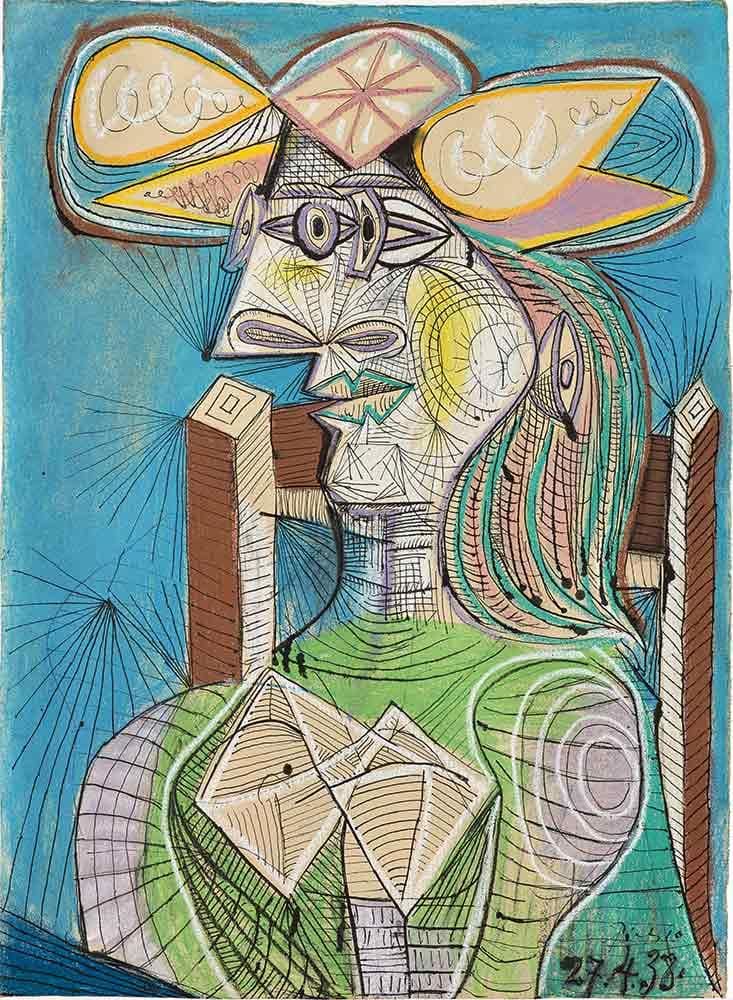

In 1917, Picasso married the Russian ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova, his first wife and the mother of his eldest child, Paulo Picasso. She provided inspiration for a new wave of experimentation, for which the artist merged Cubist shapes with more classic approaches. When his son was born in 1921, the artist began to explore the idea of motherhood, painting Khokhlova as a maternal muse. Picasso’s picture of married bliss, however, was far from his reality. Pathologically jealous thanks to her husband’s infidelity, Khokhlova suffered from a nervous disorder that would affect her for the rest of her life.

In 1921, Khokhlova’s troubles escalated further when Picasso spotted the 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter in a Parisian department store. He wooed her with the lines: “You have an interesting face. I would like to create a portrait of you. I feel we are going to do great things together. I am Picasso.”

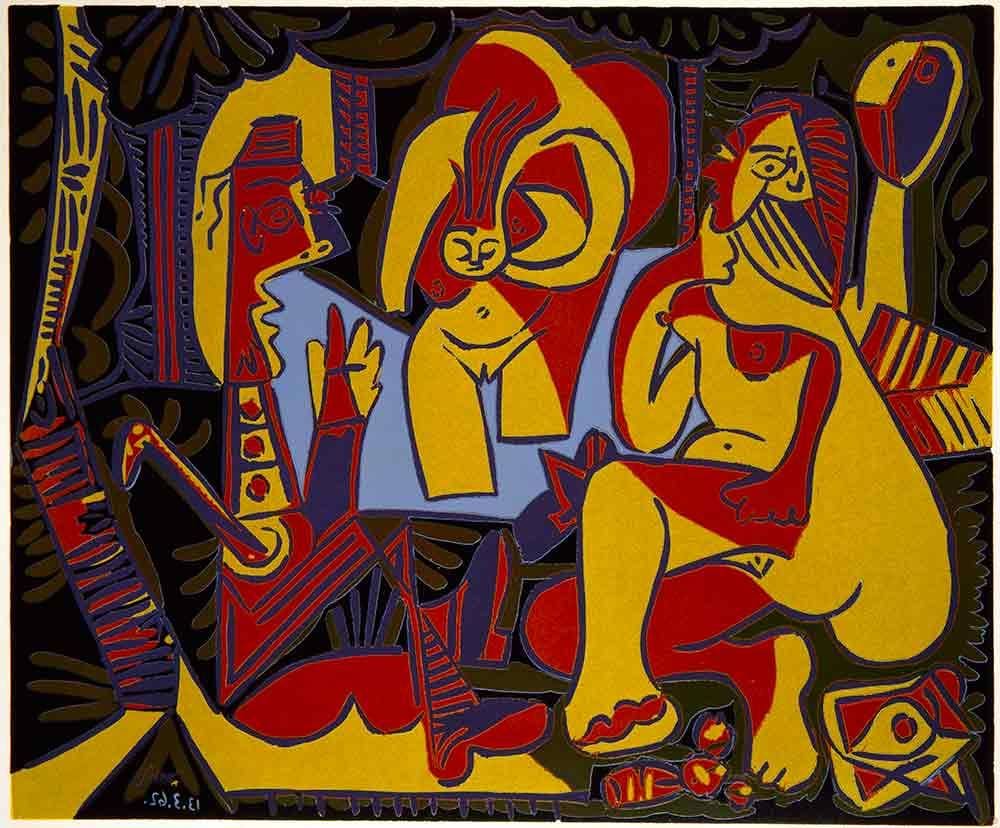

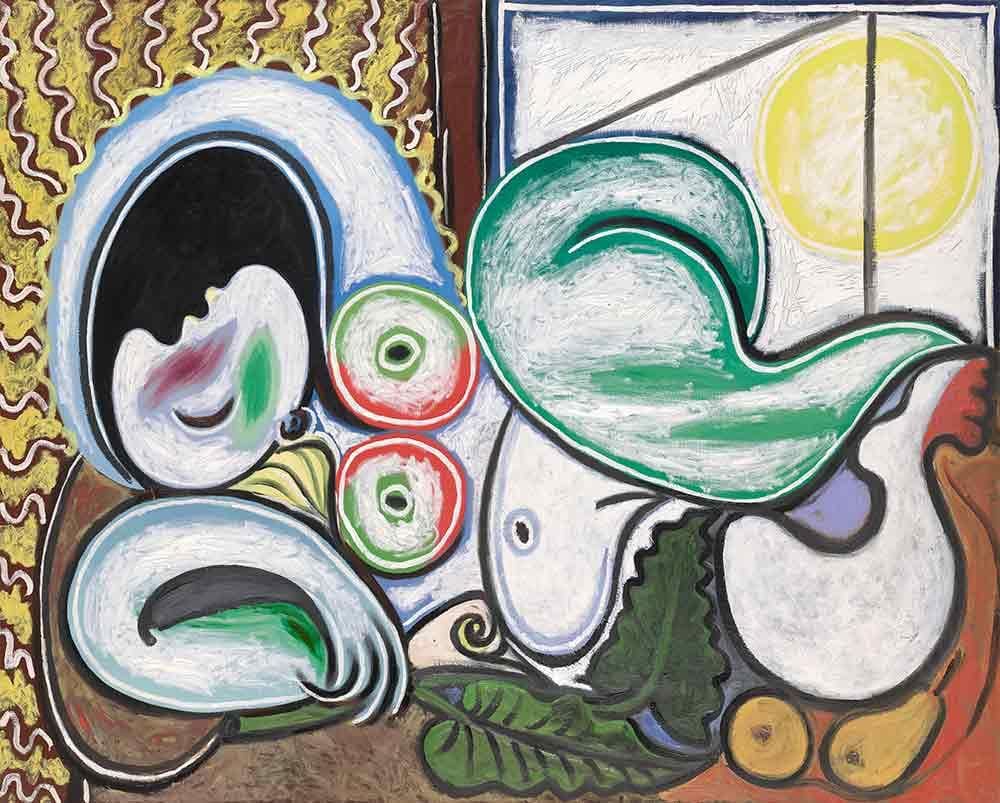

They began a secret relationship, although the artist couldn’t help but reference his personal life in his work. Walter’s influence was subtle at first, but in 1932, as part of the artist’s first full-scale retrospective at the Galerie Georges Petit, he unveiled three erotic portraits of her: Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, Le Rêve and Nude, Green Leaves and Bust. For Khokhlova, it was a clear sign another woman commanded her husband’s attention, which did little to help her mental state. By 1934, her rage over the artist’s adultery had become so violent that doctors moved her out of their apartment and into a hotel.

When Walter gave birth to a daughter, Maya Widmaier-Picasso, in 1935, Khokhlova filed for divorce. Picasso refused, unwilling to part with any of his money or property. She died of cancer in 1955, still married to him.

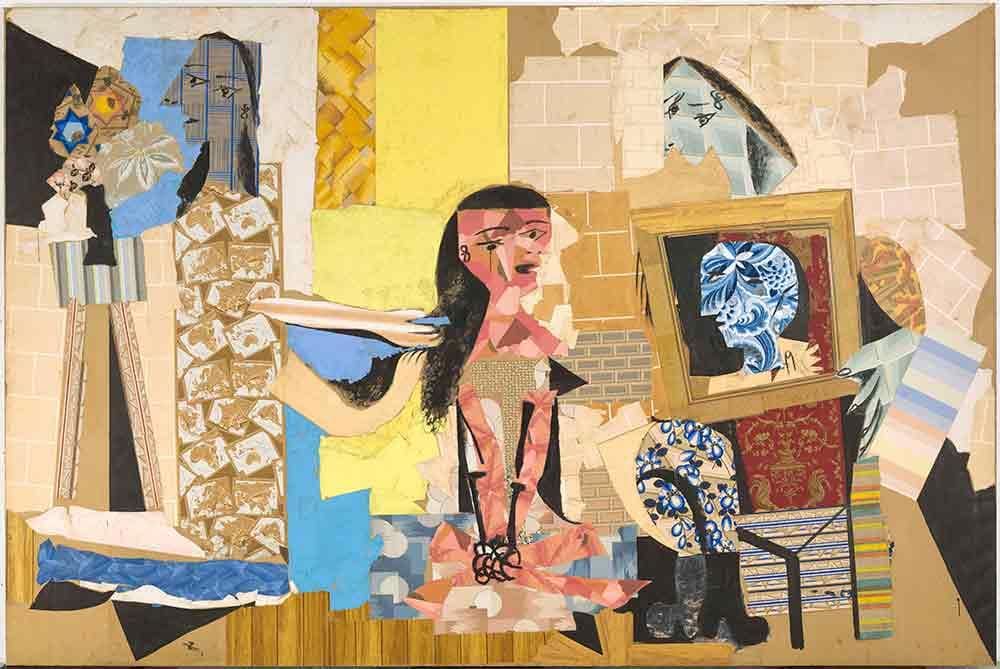

Just two months after Maya was born, the artist’s attention was again redirected, this time by Dora Maar. The Surrealist photographer, who is currently the subject of a retrospective at the Tate Modern, was introduced to the artist at a Parisian café. They were together for 11 years, with Picasso expecting Maar to be at his beck and call. She was, sitting at home all day in case he needed her – despite his refusal to end his affair with Walter.

Maar and Picasso’s relationship coincided with the beginning of the Spanish civil war and the portraits he painted of her reflect the political climate as much as they do his lover’s anguish. While he continued to paint Walter in bright colours, Maar was immortalised as an emotional wreck, most famously in The Weeping Woman. When they separated in 1944, Maar suffered a nervous breakdown and was moved to a private clinic at the intervention of her psychiatrist. “As an artist you may be extraordinary,” she told Picasso when he visited her, “but morally speaking you’re worthless.”

Next came Gilot. Despite Picasso being 40 years her senior, the 21-year-old law student left her studies for him when they met in 1943. They moved in together after three years, the first time one of his partners had done so since his marriage. She was headstrong and left him after 10 years, taking their two children, Claude and Paloma Picasso, with her. “If I didn’t leave Picasso, he would devour me,” she said.

In 1964, she released her memoir, which Picasso failed to block from publication. Furious, he refused to see their children ever again and convinced their mutual dealer to drop Gilot as a client. “Picasso was waging war on me,” she recalled, “a very dirty war, because he had all the power.” It was ultimately unsuccessful, and today, aged 98, she still paints.

Picasso met his last love, Jacqueline Roque, in 1953. He was 71 and she 26. He won her over by drawing a dove on her house in chalk, and giving her a rose every day until she agreed to go out with him. They married, and during their 20-year relationship she provided inspiration for more than 400 of his paintings, more than any of his other partners. The portraits from this period depict a domesticity and marital tenderness unseen in previous works. In Roque, it seemed, he found stability.

When Picasso died in 1973, aged 91, he left behind a destructive legacy. At the request of her husband, Roque banned most of his family from the funeral. With no will and an estate rumoured to include 45,000 paintings, £3.5m in cash and £1m in gold, a battle between his heirs ensued.

“No one in my family ever managed to escape the stranglehold of his genius,” Marina Picasso wrote. Indeed, following the artist’s death, Roque spiralled into a state of depression and would eventually fatally shoot herself 13 years later. Walter hanged herself four years after his death; Picasso’s grandson Pablito died after drinking a bottle of bleach; his son, Paulo, died of alcoholism born of depression.

In documenting Picasso’s life, his muses have proved invaluable. Along with Gilot and Olivier’s memoirs, Khokhlova and Walter kept extensive archives of photographs and letters, while Maar’s own works provided a visual picture.

“After Picasso, there is only God,” Maar famously said, having found solace in Roman Catholicism in later life. But just as Picasso’s lovers obsessed over him, so too was he dependent on them. Each relationship represented a new era of work, and a further development in his style. In remembering the greatest artist of the 20th century, it pays to consider not just the man, but the women who made him.

Where to see Picasso’s women

Picasso and Paper, The Royal Academy

This February, a major exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts will delve into Picasso’s lesser-explored medium: paper. Look out for portraits of Françoise Olivier and Dora Maar.

From £18, until 13 April, Burlington House, Piccadilly, W1J, www.royalacademy.org.uk

Beloved by Picasso – The Power of the Model, Arken Museum of Modern Art

Picasso’s muses are thrown into the light at the Arken Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, where 51 sculptures, paintings, drawings and prints track Picasso’s artistic progression and the relationships that inspired him.

Approx. £17, until 23 February, Skovvej 100, 2635 Ishøj, uk.arken.dk