Alison Jacques: The gallerist championing under-appreciated artists

It’s rare to find a gallerist that courts moderately-successful artists in the twilight of their careers. Yet Alison Jacques has a unique eye for talent that others have overlooked. Here, the London gallery owner explains why

Alison Jacques believes the future is female. And elderly. The Financial Times even dubbed her ‘the queen of old ladies’. The gallerist can be credited with invigorating the careers of numerous older women, including Brazilian painter Lygia Clark, American artist Sheila Hicks and Slovakian sculptor Mária Bartuszová; she has made a name for herself providing artists with new-found notoriety later on in life, or even posthumously. Think of it as backdating acclaim to make up for historical inequalities in the art world.

You’ve likely heard of American surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning, for example. But, I think it would be fair to say, you might not have had Jacques not got in touch with Tanning after spotting a forgotten artwork of hers in the Museum of Modern Art, New York. That was back in 2010, and Tanning was already a centenarian. Indeed, if it were not for Jacques’ determination to exhibit Tanning, she may have spent posterity being defined by the proximity to her husband, German painter Max Ernst.

Thanks to Jacques, Clark, Hicks and Bartuszová have enjoyed major international shows. Arguably Jacques’ greatest achievement, however, is promoting the lesser-known works of American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who rose to prominence during the 1980s before his untimely death due to complications from HIV/AIDs in 1989. She has been looking after Mapplethorpe’s estate since 1999.

Jacques’ foray into the art world came via a postgraduate curating course in Prato, Italy, which included a placement at the Kunstverein Düsseldorf. She then worked as an art journalist; during an interview with dealer Leslie Waddington, he offered her a job at his Cork Street gallery. Jacques’ first client was collector Charles Asprey, whom she met at an opening; the pair later joined forces and, in 1998, opened the Asprey Jacques gallery – a venture that ran until Jacques struck out on her own in 2004. On the day that her eponymous art gallery opened in a townhouse off Bond Street, collectors Charles Saatchi and Jerry Speyer stopped by to proffer their support.

In 2007, the Alison Jacques gallery relocated to Berners Street in Fitzrovia. It was around this time that Jacques began carving out her niche: she was keen to exhibit American performance artist and sculptor Hannah Wilke, who created work exploring sexuality and femininity throughout the 1970s – but it wasn’t until the end of her life, when Wilkes documented herself dying from lymphoma, that people really began paying attention.

Jacques wanted to platform Wilke, even retroactively. The gallery held an exhibition of her work, and the Tate bought a piece; the institution would later purchase Wilke’s largest installation, and her pieces can now fetch close to £1 million.

Last year, Jacques moved her gallery again, this time to a three-storey space on Cork Street, a stone’s throw from where she worked with Waddington. She did so with a renewed pledge to “discover or rediscover artists who haven’t had their dues”, as well as a promise to start taking on younger artists.

I have not deliberately chosen these artists, but I am committed to championing the work of those who were under-acknowledged during their lifetime. Many of them are women. Prior to 2000, it was a white, male-dominated art world. Mediocre work by male artists was often shown at the expense of female artists, whose work has now finally become acknowledged by museums. These female artists were previously left in the shadows, along with many great artists of colour. Thank God, in the art world, the pendulum has finally swung.

I look and I feel. It’s a gut feeling, and a belief in the importance and possibility of an artist’s presence in the world, and my need to share their voice with others.

I am passionate about creating museum opportunities for my artists. Over the years, curators have seen my exhibitions, and the resulting museum shows are a particular source of pride for me, from Dorothea Tanning and Mária Bartuszová retrospectives at Tate Modern, to Lygia Clark at MoMA, and her forthcoming solo show at the Whitechapel in London. This will be followed by a comprehensive European retrospective at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, in 2025.

This year, we have a survey show of our artist Nicola L. at Camden Arts Centre during Frieze week. I always encourage museums to exhibit our artists.

Mapplethorpe should be seen as nothing less than one of the most groundbreaking photographers of the 20th century. He was a pioneer and trailblazer, fearless to make art that was beautiful and shocking. He paved the way for what a lot of artists have subsequently been able to do by challenging conservatism and censorship.

In our recent exhibition, which marks 24 years of my collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, there were many images that had not previously been widely exhibited, proving that there is still something new to be seen despite Mapplethorpe’s death 34 years ago.

Past Mapplethorpe shows that I have staged have been curated by David Hockney, the Scissor Sisters and Patti Smith, and have included little-known aspects of Mapplethorpe’s work, such as his Polaroids and sculptures. He was not just a photographer; he was an artist, and remains an integral part of the gallery, as well as having a special place in my heart.

I am not sure I can answer that question, as I have curated so many over the past two decades – I tend to dive into each exhibition with a hook-line-and-sinker attitude. A memory fresh in my mind, however, is moving to our new gallery space on Cork Street, Mayfair. To inaugurate the space we held a solo exhibition of works by the legendary 89-year-old artist Sheila Hicks, who I have worked with for the last 12 years.

Sheila created Infinite Potential, a monumental architectural installation for our seven-metre-tall gallery (we removed a concrete ceiling during the renovation to create this incredible height). Sheila’s unique voice set the bar incredibly high for all that is to come.

I was working in Milan as an editor at Flash Art magazine. With Flash Art, I visited Unfair in Cologne – this is where I first had the idea to start my own gallery. I was inspired by the gallerists I met there, and remember thinking, ‘I’d like to be a part of this’.

I returned to London and worked at Victoria Miro, before being offered a job by Leslie Waddington on Cork Street. I remember sitting at the reception desk and dreaming of opening my own gallery there. Serendipitously, our new space is opposite Waddington. Plus, when we were installing Sheila’s show in October, British artist Ian Davenport was installing his exhibition at Waddington – I was Ian’s artist liaison when I worked there 30 years ago! It was a full circle moment and, as I don’t believe in coincidences, it felt like my new space was meant to be.

My first sale was at Waddington in 1995 to young British collector Charles Asprey, and he acquired a painting by Ian Davenport. So, my first sale was an Ian Davenport, and Ian was installing his show at the same time as our inaugural exhibition at 22 Cork Street!

I think that Mayfair and St. James’s are the epicentres of the UK contemporary art scene. Hence our new location in the heart of the area, on a street which is rich in gallery history, with legendary gallerists such as Robert Fraser having trailblazed here in the ’60s. I love the fact that the inspirational Peggy Guggenheim – whose museum in Venice I worked in during the ’90s, and who gave me my lucky break in the art world – had a gallery in the ’30s at 30 Cork Street. Another coincidence…

I do work with younger artists. To be honest, the age, gender or background of an artist is completely irrelevant – it’s all about their art.

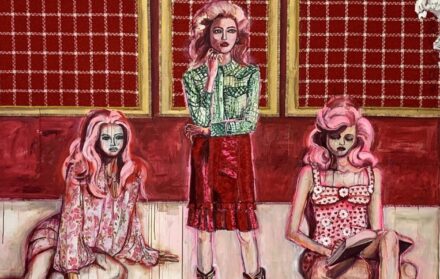

Graham Little, who I have worked with for two decades, currently has a survey exhibition open at the FLAG Art Foundation in New York – his first solo presentation in the United States. I also represent young British artist Sophie Barber, who graduated in 2017, and has already had her first solo public space exhibition at Goldsmiths CCA [London], and has a forthcoming solo museum exhibition at Hastings Contemporary.

We just opened an exhibition of paintings and sculpture by Betty Parsons. Her prowess as founder of the legendary Betty Parsons Gallery has obscured appreciation for her own practice. She gave now-famous artists, including Barnett Newman and Robert Rauschenberg, their first solo exhibitions, but parallel to this, she was working away on her own art.

My desire to show Betty’s work is driven by a belief that she was a great artist who should be viewed alongside the artists that she discovered. Her painted sculptures, made from driftwood she collected on the beach near her studio, reveal a unique voice that needs to be heard.

I am only sorry that Betty is no longer here to experience the international recognition her work is now receiving.

Alison Jacques, 22 Cork Street, W1S, alisonjacques.com