Dukes London: a St James’ institution

History seeps through the walls of Dukes London, where Ian Fleming drank dry martinis and Edgar Elgar composed symphonies. But more than 200 years since it opened, the hotel remains a refreshing keyplayer in the capital’s

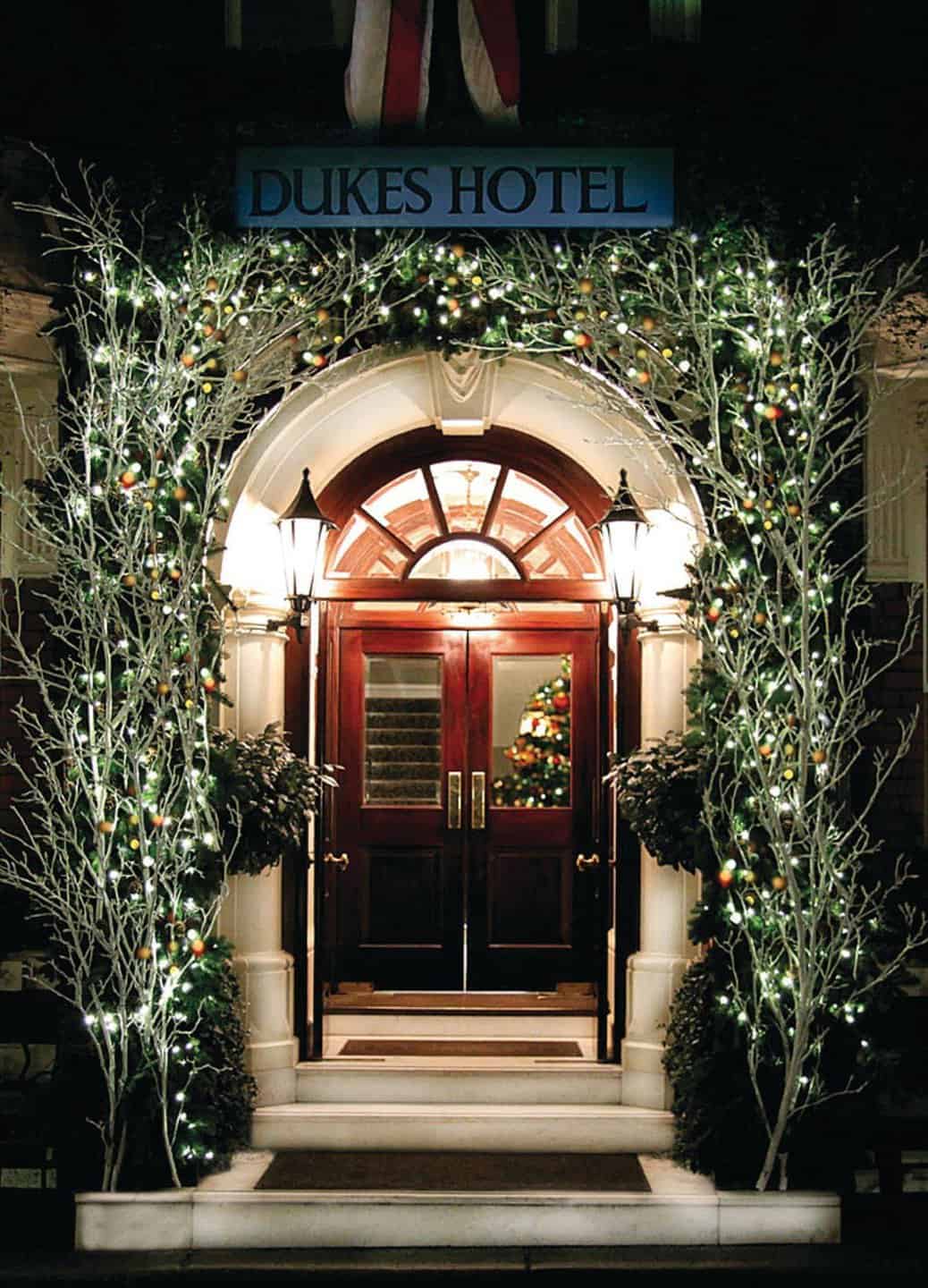

Dusk in St James’s Place and the sound of ancient doors being gently eased shut echoes around the courtyard. A Union Jack hangs above the porch that leads to the Dukes London hotel. We’re in central London but the hush is almost absolute. St James’s is a neighbourhood so totally dedicated to discretion that even Mayfair seems somewhat vulgar in comparison. I don’t plan to step back from this bijou courtyard onto the main thoroughfare of St James’s Street tonight but it’s reassuring to know that, in an area of such fabulous wealth, I’m just the discreet hurl of a tournedos Rossini away from the master vintner Berry Bros. and Rudd, the cigar merchant James J. Fox and the milliner Lock and Co.

All these stalwarts are old enough to have been familiar to Beau Brummell, the ultimate Regency dandy, who considered this street to be almost his personal domain. Come nightfall and Brummell had the gentleman’s club White’s to retreat to for claret and, according to legend, betting binges which would include placing wagers on which raindrop would run down the club’s front window the fastest. Now, just as in Brummell’s time, White’s does not admit women and, even with my gender advantage, any potential new member needs to be vouched for by some 35 signatories. In short, I’m in need of a more open-minded welcome.

Welcoming people is what Dukes has been doing since 1908 – though if you’ve spent the majority of your adult life being processed through the corporate blandishments of luxury chain hotels then you may find the Dukes welcome somewhat startling at first. This is not because it’s particularly quirky or overly obsequious. Rather, it’s because, more than that of any other hotel I know in London, it is absolutely, bona fide genuine – unless the staff are some of the greatest actors currently performing in the English language.

Dukes is small; just 90 rooms and suites. And if your idea of luxury is multi-room apartments with flat-screens the size of football pitches and corridors long and winding enough to require a trail of brioche crumbs in order to navigate your way back to the bathroom, then Dukes will displease you. Rooms are cosy – even the Duke of Clarence penthouse is no larger than the ground floor of a mews house in Belgravia. The balcony, with a direct view across to the butterscotch edifice of Clarence House (home of Prince Charles and formerly the Queen Mother) could comfortably hold two adults, though a Duchy Originals biscuit barrel or a Windsor-family-sized G&T on top of this would prove a tight fit.

My superior room has mustard-coloured bed runners, a marble bathroom with water pressure powerful enough to fell an otter, dark chocolate oak wardrobe doors and duvets with a thread count so high that it could only be calculated by NASA. These are rooms designed not just to be slept in through the nocturnal hours, but to be lived in for entire afternoons of cold champagne and hot showers.Pad through the corridors and you’ll stumble upon the elevator (dating back to opening day) which still has a cushioned bench in it in case the idea of standing up for the entire 20 seconds it takes to travel from the top floor to the bottom is too exerting. There’s a drawing room filled with wingback chairs, a tiny cigar garden, oil paintings of the Duke of Sussex, gently ticking clocks and an atmosphere redolent of an age where the first alcoholic drink of the day should be taken at around 11am; ideally with a copy of the Illustrated London News and a waiter who will discreetly inform you of the odds for the afternoon’s racing.

St James’s Place itself can be traced back to 1532, when Henry VIII built St James’s Palace on the site of a former leper hospital. The palace was among his preferred locations for clandestine trysts with his soon-to-be second wife Anne Boleyn. Home to a small inn until 1885, the current Dukes building was first used as the London chambers for the sons of British aristocracy before finally becoming the hotel we know today. In the Georgian and Victorian townhouses that surround Dukes are rooms where Lord Byron and Oscar Wilde wrote and Chopin performed. Edward Elgar was a regular guest at Dukes in its early years and the hotel seems to have taken the composer’s Variations on an Original Theme as inspiration when it comes to the recent restaurant makeover. Chef Nigel Mendham’s previous incarnation here, a deep carpeted, reverential hush of foams, drizzles and reductions called Thirty Six, has been stripped back to create GBR – Great British Restaurant, still helmed by Mendham.

Parquet floors, glass cabinets full of barolo and chablis, chrome and granite surfaces, mirrors galore, lengthy padded banquettes and framed photos of cigarette and Scotch-fuelled mid 20th-century aristocratic dinner parties all contribute to a look that discreetly squeezes the elbow of Art Deco. This room is like The Wolseley but without the daily crush of PR client meetings. The menu, unusually, allows diners to eat any dish in either starter or main course size. This allows for both restraint and excess within the same meal; the former exemplified by an impeccably constructed risotto with charred leeks and chestnut mushroom broth; the latter by an outrageously sybaritic rose veal tomahawk with French fries for two.

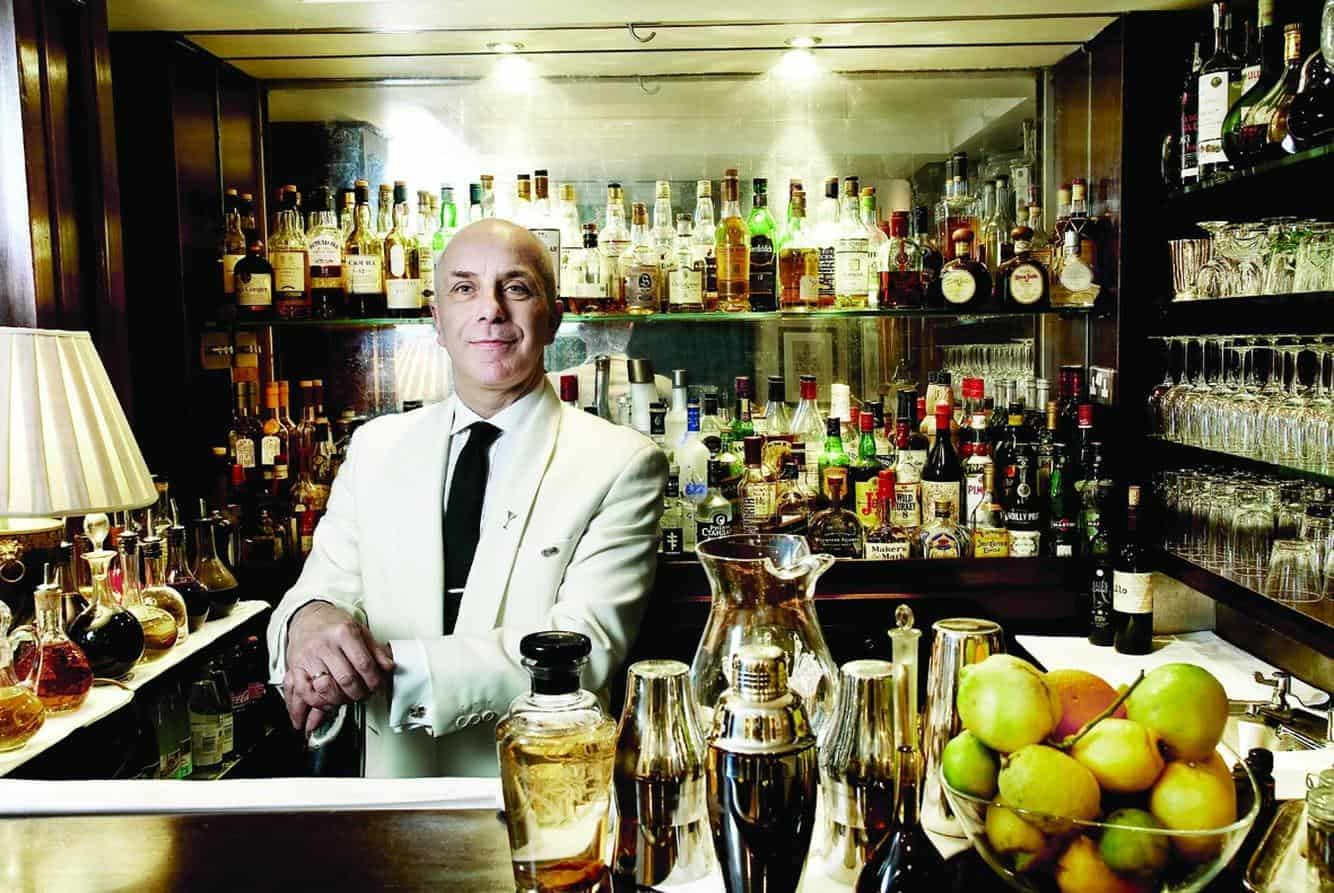

There’s a bar counter in GBR but it’s as superfluous as a hairbrush gift set for Bruce Willis. Everything you need to know about this hotel’s dedication to drinks is downstairs, just to the right of the front door. Dukes Bar is, of course, where Ian Fleming, James Bond’s creator, is supposed to have decided upon 007’s favoured tipple. There is a strict no-music policy (frankly, tinkling jazz would render the entire experience overly ersatz) and the rituals to drinking a martini here are as much about the visuals as the taste. Let one of the white-jacketed barmen, who mostly look old enough to have served Fleming himself, wheel the rosewood trolley to your table and give your V-shaped glass a rinse with some dry vermouth from the Sacred distillery in north London.

Then comes the gin, so cold it’s almost as viscous as treacle. Then a twist of peel from a large Amalfi lemon and the five, yes five, shots of gin (the hotel favourite is City of London). Nobody in their right mind actually asks for their martini to be shaken, not stirred. And nobody, with cocktails these strong, orders more than two. Try to purchase a third and you’ll be refused. It’s about the only time you’ll hear the word ‘no’ in Dukes. The rest of the time, from the unusually high tolerance of dogs to a willingness to deliver a plate of H. Forman Scottish smoked salmon and a bottle of champagne to your room at 3am, the answer to almost every question seems to be “with pleasure”.

Freedom isn’t a word often associated with hotels these days; a culture of hidden add-ons, ruthlessly applied check-out times and breakfast buffet queues see to that. Dukes is a glorious exception – and perhaps one of the last. Just like its martini, this is a hotel that gently stirs the senses without shaking the historic ground it sits on.

Rooms from £350 inclusive of VAT and breakfast,