Fizz-ical Endurance: Champagne in World War One

Renowned for its luxury fizz, the French region of Champagne was also the scene of great tragedy during the First World War. A century after the 1918 armistice, the area still bears poignant scars

The handwriting, carved into the cool limestone wall with a steady, educated hand, translates into English as “I am on the front lines since the first day of war.” The words convey an innate sense of weariness. Written by a French soldier whose name is lost to history, those simple lines were written at a time when bubbles and bloodshed would become the most intimate of bedfellows, both above and below the fields of the Champagne region.

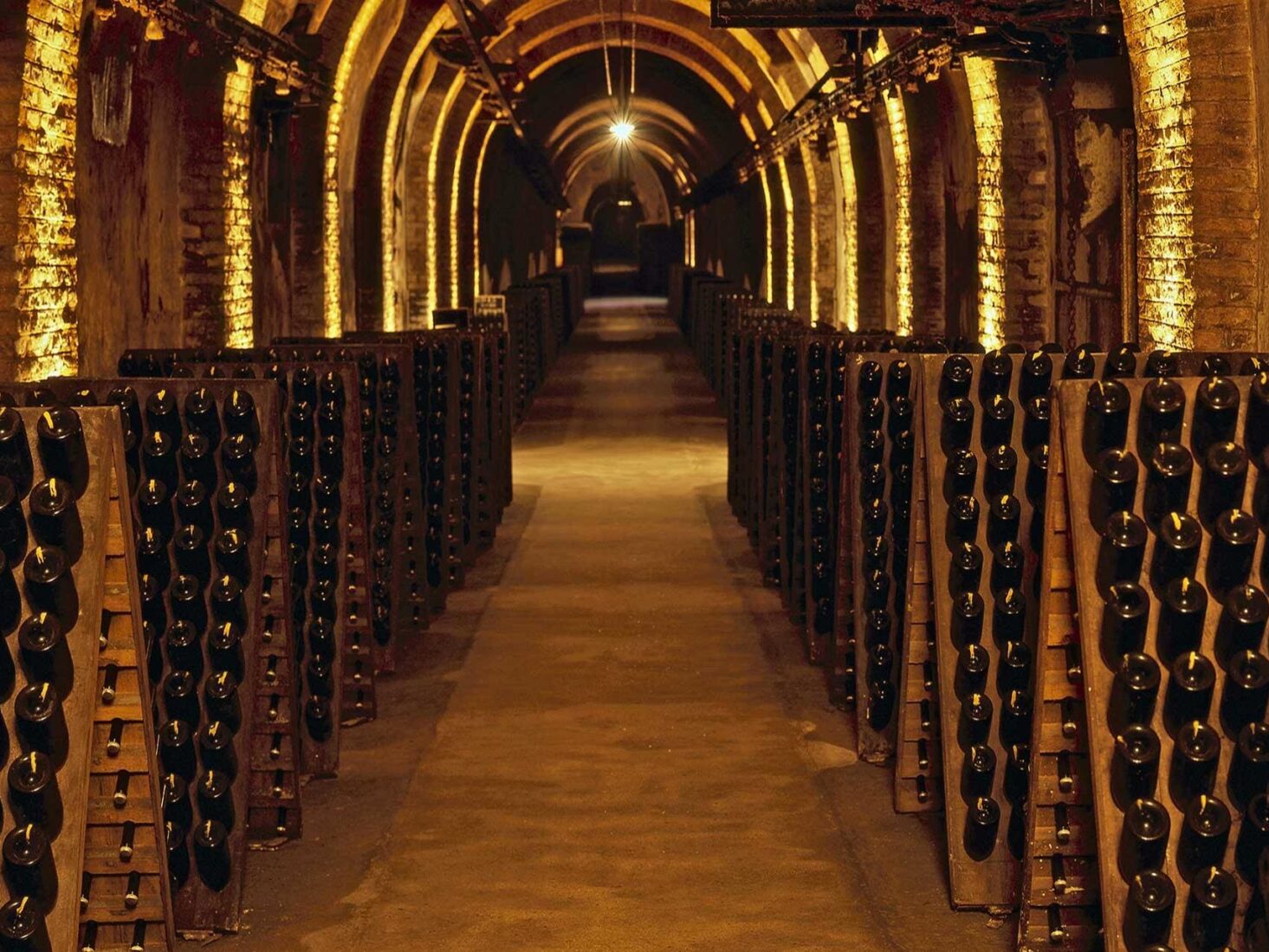

The cool, damp expanses of the Taittinger champagne house cellars date back, in part, to the 13th century. But it was the events of 100 years ago that have led me to this vast underground complex where, for the duration of the Great War, champagne played its part in keeping this region of France out of German hands.

A wine lauded by kings, queens and Kanye West alike, it’s worth remembering that, were it not for the questionable drinking tastes of the British, champagne would be considered nothing more than a fizzy disaster, waiting to be poured down the nearest drain. It was mid-17th century London café society that took a shine to this delicate, highly acidic wine from France. Back in Champagne however, effervescence in wine was considered to be a disaster. If the wine fizzed, it was considered ruined.

Once the peculiar tastes of the ‘rosbifs’ across the Channel became clear, perceptions quickly changed. The number of bottles that exploded en route to Mayfair and St James’s led to champagne establishing its exclusivity. The Brits partially solved that problem by creating bottles with thicker glass, but costs remained high. To buy enough grapes to create one bottle of champagne in 2018 costs champagne houses around £15; that’s before bottling, storing, labour, promotion or transport. Despite all this, and the increased popularity of prosecco, the UK remains the world’s number one market for champagne.

The summer of 1914 was exceptional for the best and worst reasons in Champagne. Vineyard workers, mostly women and children due to the conscription of local men, plucked the vines of chardonnay and pinot noir grapes with the noise of shell fire rumbling in the near distance.

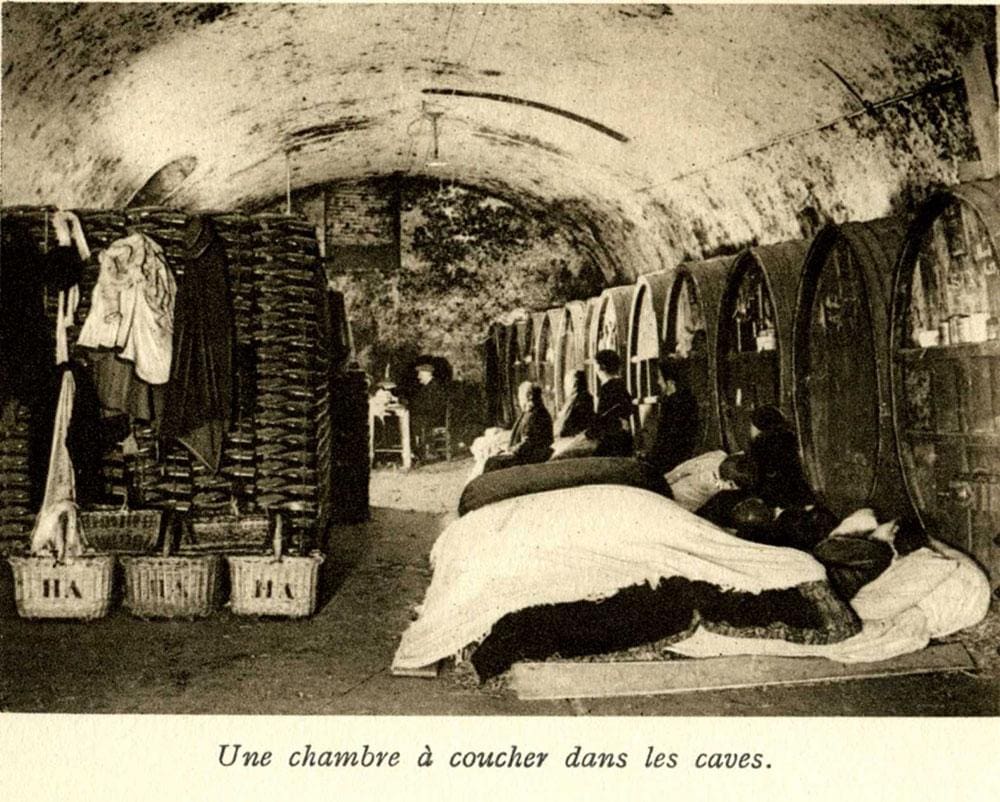

When German troops invaded, local citizens took to the cellars of the region’s champagne houses. Schools and hospitals were moved underground, with racks of champagne bottles as a backdrop to this new subterranean life. Incredibly, the bubbly from that summer is considered to be one of the best vintages of the last century.

The Allies retook most of the region within weeks but the next four years would see a continual, immensely bloody war of attrition between the opposing forces, with the champagne house cellars again coming into use as prisons for captured German soldiers. A century on and the atmosphere in the villages, fields and hillsides surrounding the main regional centre of Reims will be familiar to anyone who has visited the better-known battlefield areas of Belgium. It’s a feeling of sombre, melancholic emptiness; a memory echo of a particular barbarity that, to this day, has few parallels.

The Musée du Fort de la Pompelle is just one of the physical reminders of the destruction of this region. Built after the Franco-Prussian wars of the 1870s, the fortress was reduced to near ruins by German bombardment. Today, little has changed: the remnants of the buttresses and towers, hewn out of chalk, lie topped with flowers and weeds. A small museum in a surviving portion of the structure houses an extraordinary collection of German military headgear from the era, as well as a selection of Allied uniforms. The red-cuffed dark navy tunic and flat-topped kepi hat of the French army in 1914 qualifies instantly as the most raffishly fashionable and debonair army attire of all time, albeit entirely unsuitable for a prolonged stay in a trench.

There are over 2,000 different houses, co-ops and independent growers in the fields of Champagne, and many are local farmers who own barely half a hectare of land. Such is the value of the grapes from this fine chalky soil, however, that even such a minuscule portion is easily enough to keep a family in Monaco apartments and brand-new convertibles for generations.

The major champagne houses like Taittinger and Pommery give fascinating, albeit sometimes overly slick and faceless talks, tastings and tours through their cellars. But it’s the more humble co-op producers who have the most interesting stories to tell. Visiting the Maison Collet co-op is a reminder that all was not joie de vivre in these parts, even before the Great War. Collet is located on the site of the Bissinger champagne house; most of its current home was burnt to the ground by a rampaging mob in the 1911 Champagne Riots, which were fuelled by a growing anger at the champagne houses’ habit of selling fraudulent champers at huge cost to local growers.

The one building that survived the blaze is a wonderful, creaking, wooden structure, complete with cream and brown flaking paint on the stair bannisters, century-old bottles and displays telling the full story of how, after the riots, the quite astonishing levels of fraud were done away with. Never again would ‘champagne’ be made with Spanish and German grapes, and even, in some cases, rhubarb imported from England.

For some enthusiasts, the terroir of this famed region gives up a lot more than just supreme wine. Since 2012, amateur archaeologists have been painstakingly removing the soil around the fields of La Main de Massiges to reveal preserved Great War trenches. Walking the narrow, contorting corners of these fearful defensive lines, it’s not difficult to imagine the claustrophobia and terror that must have infested the minds of the soldiers amid the mud, lice, rain and mustard gas. The remains of a field hospital still stand alongside remnants of war that continue to be dug up by the week. I saw broken spades, saucepans and shards of plates on mournful display inside the various dugouts, and, yes, a large amount of mud and dirt-encrusted wine bottles.

The screening room of the Centre d’Interprétation Marne museum nearby shows a film which is gratifyingly light on exposition, focusing almost entirely on the letters exchanged by the Papillon family – three brothers and one sister, the eldest of whom, Joseph, would die on the front line. One of his last letters is almost unbearable in its despair and pathos. “Let those who started this war fight it,” he writes from the trenches. “I am utterly sick of it. And I’m not alone.”

The sheer scale and number of men who fell on this rich and verdant soil seems to have been absorbed by the breathless quietude of the landscape and the marquetry of the fields. Those immaculate rows of vines bear an eerie similarity to the near endless columns of stone crosses in the cemeteries. In the pellucid autumnal afternoon sunshine, a century on from that unthinkable slaughter, a soft breeze ruffles the vines. The crosses stand still in an eternal, silent salute.

Champagne, 1914-15 (an extract)By Alan Seeger, an American poet who died aged 28 on 4 July 1916 at the Battle of the Somme

In the glad revels, in the happy fêtes,When cheeks are flushed, and glasses gilt and pearledWith the sweet wine of France that concentratesThe sunshine and the beauty of the world, Drink sometimes, you whose footsteps yet may treadThe undisturbed, delightful paths of Earth,To those whose blood, in pious duty shed,Hallows the soil where that same wine had birth. Here, by devoted comrades laid away,Along our lines they slumber where they fell,Beside the crater at the Ferme d’AlgerAnd up the bloody slopes of La Pompelle, And round the city whose cathedral towersThe enemies of Beauty dared profane,And in the mat of multicolored flowersThat clothe the sunny chalk-fields of Champagne…