886: Inside the Royal Mint’s foray into sustainable fine jewellery

As it opens its first bricks-and-mortar store in Burlington Arcade, 886 creative director Dominic Jones explains why heritage and ethics will always be at the company's heart

Did you know that every kilo of X-ray film contains up to five grams of pure silver? And I’m not talking diamond drill bit unusable offcuts. I’m talking top-grade 925 silver that even Tiffany & Co. wouldn’t turn its nose up at. So, what happens to all this precious metal once it’s been used to reveal broken legs and fractured ankles? It goes up in smoke. Literally.

Current law decrees that all medical records must be kept on file for seven years. After that, the enormous cost of renting secure warehouses to store these documents means the NHS often elects to incinerate them – taking all that gorgeous silver with it. Well, until 886 by The Royal Mint stepped in, that is.

Founded in early 2022 out of a desire to preserve the unique techniques and craftsmanship of the Royal Mint via a commercially viable fine jewellery business, sustainability has always been at the heart of 886. Its early pieces were made using gold salvaged from old electronics and, as of October 2022, it is one of only three jewellery brands in the world to use X-ray Silver.

It’s a no-brainer, really. As well as being both environmentally- and ethically-sound (the silver mining business is even murkier than the gold), Betts Metal, which pioneered the extraction process, buys the X-ray film from the NHS, creating thousands of pounds in new revenue each year for vital healthcare services.

So, what took so long? The sad truth, explains a spokesperson for Betts Metal, is that, until recent years, there simply hasn’t been the demand. The technology to recycle silver in this way has been around for decades (and Betts has been doing it in a small way for more than 50 years) but only now has consumer awareness of the importance of provenance and traceability reached a level where silver extraction is cost-effective on a commercial scale.

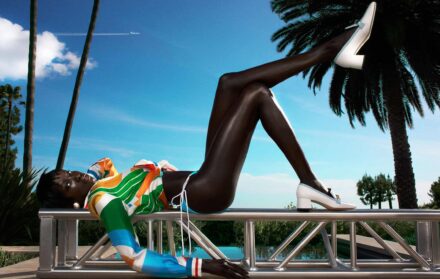

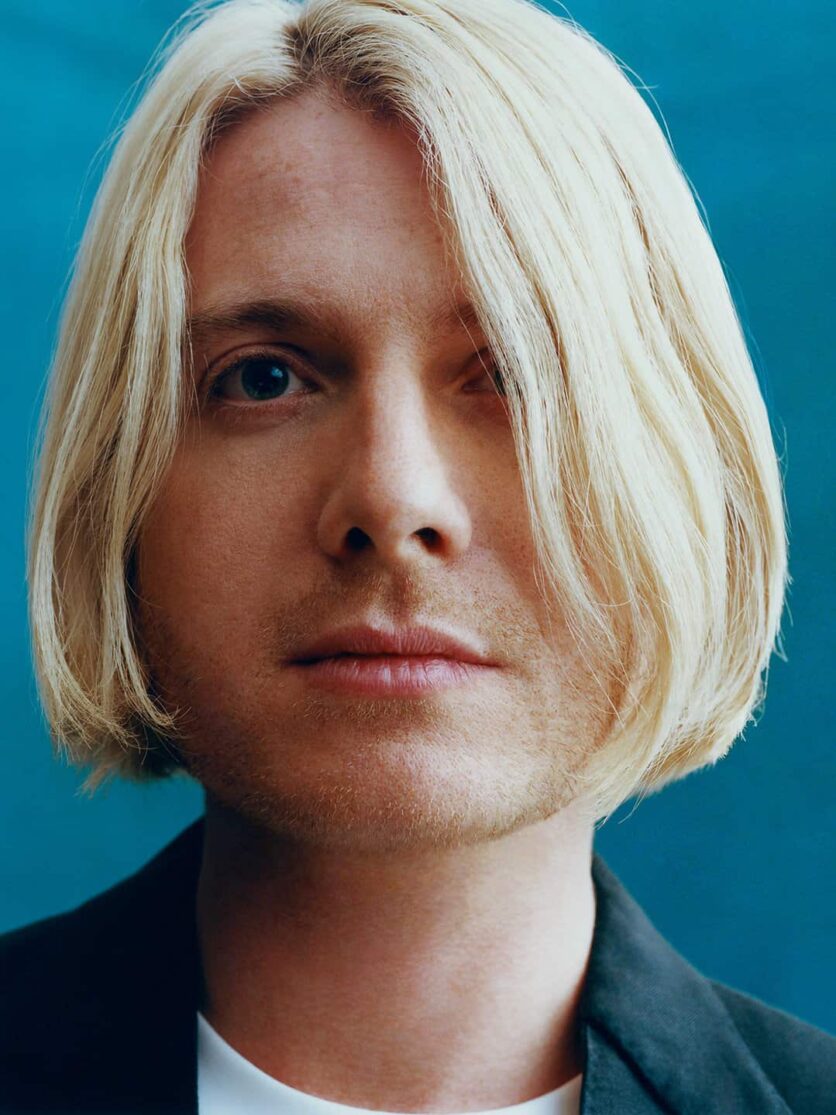

Of course, all this means nothing if the jewellery itself isn’t covetable. For this, 886 turned to British designer Dominic Jones. A five-time BFC Newgen winner whose sculptural ‘Tooth and Nail’ designs found fans in David Bowie, Harry Styles, Beyonce, Rihanna and Karl Lagerfeld, it was an appointment that raised eyebrows among those in the know. Jones was revered for his punky, contemporary aesthetic. How was that going to play out at a storied institution like the Royal Mint?

The answer lay in a shared passion for supporting craftspeople and an unwavering commitment to producing the kind of jewellery that would be treasured for generations. The result is a collection of minimalist, tactile and genderless pieces that you’ll want to wear every day, whether you’re 17 or 70.

As the house prepares to open its first bricks-and-mortar boutique in Burlington Arcade, Jones takes us inside the world of 886 by The Royal Mint.

They drew me in! When they first reached out I was curious; what did the Royal Mint want with me? They’d come to the decision that they wanted to make jewellery and saw that as a path for expanding the business. Initially, they wanted to talk to me about what I saw a creative director doing and then they asked me to come up with a creative concept of what a jewellery brand for the Royal Mint could look like. As my ideas evolved, so did my dedication.

There were also some outliers that I thought were quite special. The fact that the initial premise was for the brand to be a vessel for growing manufacturing, growing skills and supporting heritage crafts really spoke to me. I love that the measures of its success aren’t purely financial, it’s also about how many jobs we can save and how many we can grow and build.

The Royal Mint was moved to Llantrisant [in South Wales] in the ’70s in a bid to create manufacturing jobs in metalwork and small-scale crafts. The way the Royal Mint produces is through striking. So, instead of casting, which is when you pour molten metal into a mould and cool until solid, it uses cold metal and presses it into the mould by squeezing it under high tonnage. There are lots of similarities with traditional jewellery making but it’s a different take. There’s also an amazing history of engraving at the Royal Mint.

The premise of building British manufacturing and jewellery jobs was, in itself, a path to what the brand would be. If we were going to be manufacturing in England it couldn’t be disposable, cheap jewellery. It had to be high quality and proper fine jewellery to hold the margins. We could never have gone up against a Pandora or someone like that.

Then, with the research, I went back to the beginning of the Royal Mint. I looked at the idea of providing a secure place for holding value through money which, in turn, led to the idea of creating jewellery that held value through its material. It’s that very old concept of a wearable asset. In India, for example, it’s very traditional to wear your life savings on your wrists. In the last few decades, Western society has been on a different journey; it’s been a kind of race to the bottom and not so much about the actual material value. It’s taking it back to an older vision of jewellery.

I love the cuff. There’s so much depth to it. When I was younger I had a bit of a wayward friend whose dad made him a gold bangle with notches on it to measure the value of the gold. The idea was that if he ever washed up on shore on his travels around the world, and he’d lost his wallet and his phone, he could go and get a section cut out of it and it would be a certain amount of gold. On the inside of my cuff, I’ve got notches that give a visual representation of what 10 grams of gold looks like so you know that, if you need to, you can chop that bit off and it would be worth that amount of money. There’s also some hidden poetry on the underside which is just for the wearer. It has some lovely details.

One of the ideas in the initial brief was that 886 would open out to homeware as well. Often when jewellery brands do homeware, it’s like everyone’s just pulled their fancy Christmas crackers and you’ve got a little earring and a little photo frame and a little selection of expensive nick nacks. I felt that if we were going to say we’re a jewellery and homeware brand, we had to tackle each part of it with authenticity. I wanted to find people who were doing each section well and collaborate with them.

One of the reasons I was drawn to Maker’s Cabinet was that they do everyday objects but their designs are so intentional and beautifully designed that they have this precious quality to them. I worked with what they’d already done and overlaid the approach from my collection, referencing the same curves and the same forms and the same finishes, so that it followed through into those pieces.

For a start, it showed that the Royal Mint was thinking in a modern way. I already knew they must be to be contacting me; I’m fully qualified and have a huge set of skills but I’m also a modern, young designer. That’s a brave choice. From the very beginning of my career, I’ve been interested in sustainability. I pushed my own jewellery brand to work with the World Land Trust and I used my leverage to support endangered ecosystems. It’s always been part of my personal brand so I’m glad to see that the rest of my industry has caught up and is making efforts to be sustainable.

The other brands using recovered gold will be doing it manually by picking and burning it off. We use a unique cold chemistry process which means that we’re not having to manually scrape or burn the gold off, which is just much more realistic long-term. The Royal Mint has taken this process from theory to reality and has invested in building a huge manufacturing base. Hopefully, it will be able to produce materials this way for the industry at large.

To be honest, the rest of the industry is kind of its own beast. I don’t think it would be right for me to speak on what everyone else should do. I know that what we’re doing is building our entire business model around sustainability so we, as a company, will hopefully provide a good example for others to follow.

Not in the jewellery because they’re not precious alloys, and we’re only ever going to be selling silver and gold, but certainly it’s something we’re looking at for homeware. As the company grows, we’ll be looking at how we can tie in more and more of the history.

It was something I always wanted. Fine jewellery has a price point that works best sold through physical retail, rather than online, and the collection I started with was intentionally understated so it left room for us to talk about all of the things that made the jewellery unique. There’s so much storytelling involved with each of these pieces that it just makes perfect sense to sell them in our own environment with our own people.

886 The Royal Mint’s Burlington Arcade boutique is open now, visit 886.royalmint.com