Is body diversity in fashion a lost cause?

After making headway in recent years, the last few fashion seasons have seen progress in terms of representation slow and, in some cases, even reverse. What happened?

Haute Couture Fashion Week is currently taking place in Paris and, as ever, it’s a spectacle. The presentations promise the best and boldest in fashion (last season Schiaparelli sparked controversy by affixing fake, life-sized animal heads to its garments), so prepare to be shocked – and in more ways than one. Fashion events reliably draw comment not just for the clothes, but for the models wearing them – and, most specifically, how thin they are.

It’s a tricky one to discuss – public scrutiny of women’s bodies should, of course, be avoided. But when models are resorting to sucking on orange juice-soaked cotton balls to lose weight (as model Charli Howard has publicly stated she did in her teens and early 20s), something has gone horribly wrong.

Not to mention the knock-on effects: the promotion of unattainable body ideals is a very real contributor to the mental health crisis. According to an Ipsos survey, 79 per cent of Americans report feeling dissatisfied with their body. The National Organization for Women claims that 45.5 per cent of teens have considered cosmetic surgery. The prevalence of eating disorders has more than doubled in the past two decades.

How did we get here? Well, society has always had opinions on what is ‘right’ and ‘desirable’ in a woman’s appearance (think everything from corsets to skin bleaching treatments), but the modern era’s obsession with thinness can be traced back to the 1960s, when androgynous, straight-up-straight-down figures like that of British modelling legend Twiggy were in vogue. It was the ’90s, however, that really heralded the cult of ‘size zero’ and the arrival of ‘heroin chic’.

Kate Moss in 2004. Image: Shutterstock/Everett Collection

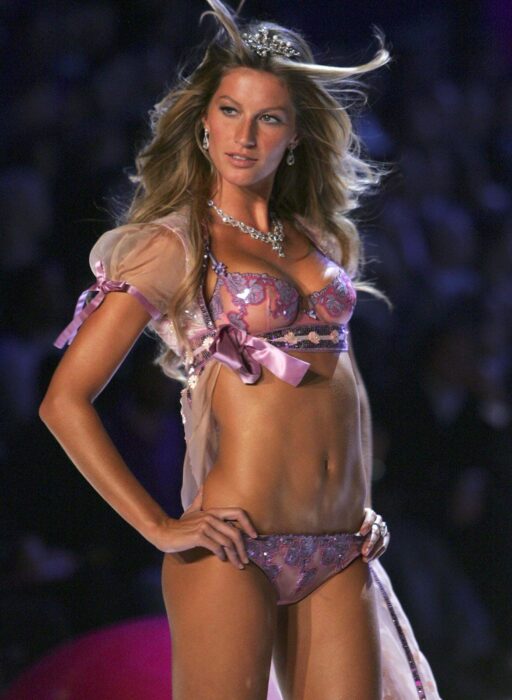

Gisele Bündchen modelling for Victoria’s Secret in 2005. Image: Shutterstock/Everett Collection

The aesthetic was popularised by photographers like Corrine Day and Davide Sorrenti, who depicted waifish women with coltish limbs and dark circles under their eyes. Kate Moss was its poster child, leading the charge with the infamous mantra ‘nothing tastes as good as skinny feels’ (she later reneged on this statement, but it had already become the rallying cry for girls with eating disorders everywhere).

‘Heroin chic’ lost momentum after Sorrenti actually died of a heroin overdose, which shook the fashion industry sufficiently enough that a new in-demand aesthetic was born, embodied by the tanned, athletic Gisele Bündchen, with Vogue announcing ‘the return of the sexy model’.

But the horse had already bolted. The messaging of the ’90s found its way onto ‘pro-ana’ (pro-anorexia) Tumblr forums and the pages of judgemental women’s magazines, and women of the noughties remained subject to the same punishing standards as they had been the decade before.

By the end of the 2000s, however, the tide was starting to turn. Comments made by Karl Lagerfeld, who said that people prefer to look at ‘skinny models’ and that those who do not are ‘fat mummies’, felt at odds with the cultural measure of the day and were largely condemned.

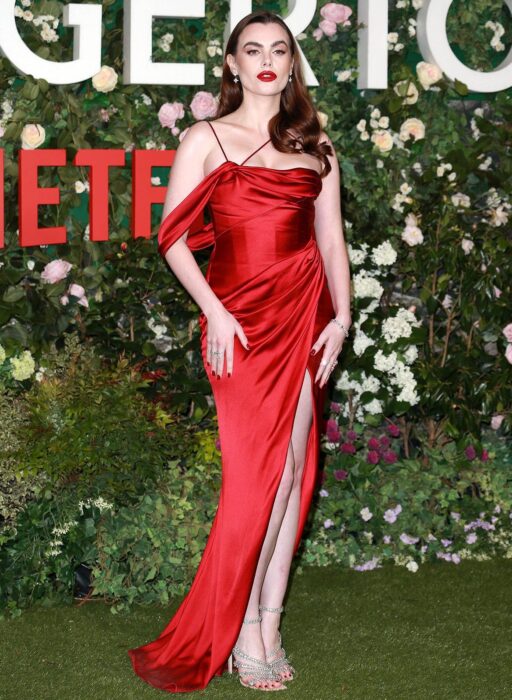

Charli Howard. Image: Shutterstock/Fred Duval

Ashley Graham on the Christian Siriano runway during New York Fashion Week AW19

In the 2010s, a wave of genuine body positivity was building. In 2015, Howard, who was dropped from her agency because of her weight when she was a size 6-8, penned an open letter about her experience which went viral. In 2016, Ashley Graham became the first ‘plus-size’ model to be on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

It felt symbolic when Victoria’s Secret – the brand that, perhaps more than any other, hitched its wagon to normative beauty, digging in its heels again and again with regards to recruiting larger or divergent bodies to its roster of ‘Angels’ – went into administration in 2020, having lost 16 per cent of its share of the intimates market since 2015. Even more telling, it later resurfaced with a campaign fronted by plus-size model Paloma Elsesser, and a statement from its chief marketing officer claiming that VS had ‘gotten off track’ and promising to ‘[show] more types of women’.

It all culminated in 2022. During the major international fashion weeks, brands like Chet Lo, 16 Arlington and Di Petsa presented shows that were notably, deliberately diverse. SS Daley sent larger male models down the runway, and Karoline Vitto hired curve models exclusively. So, you can imagine my (and many other industry commentators’) surprise during fashion month last February, when the models were, once again, undeniably and pervasively thin.

Sinead O’Dwyer AW23

Sinead O’Dwyer AW23

Vanessa Friedman, fashion director at The New York Times, tweeted, ‘Even I am distracted by the extreme skinniness of many of the models in Jason Wu’s show’, while former Vogue editor, Naomi Pike, described the ‘return to a very singular celebration of body types on the catwalk’ as ‘really disheartening to witness’.

Aside from a few instances – like Precious Lee closing Thom Browne, and with the notable exception of Sinead O’Dwyer, who sent a pregnant model and a model who uses a wheelchair down the runway – AW23 felt like we’d been beamed back to the ’90s.

The numbers confirmed the hunch: New York Fashion Week SS23 was the most body diverse to date, with 49 plus-size castings. The following season, that fell to 31. Vogue Business reported that across New York, London, Milan and Paris, only 0.6 per cent of the models were plus-size. Why the U-turn?

At the end of last year, the New York Post published an article entitled ‘Bye-bye booty: Heroin chic is back‘. It received backlash from audiences who refused to accept that years of progress on the body positivity front was merely another trend, but, in fairness to the author, the headline was an accurate reflection of the current cultural moment. Anyone with a working knowledge of fashion will be aware that Noughties, or ‘Y2K’, style is back in a big way – a trend that, with its low-rise jeans and sky-high crop tops, is intrinsically linked to a specific body type.

The launch of Miu Miu’s spring 2022 collection, which featured boob-grazing jumpers and low-slung micro-minis, became a ubiquitous symbol of Y2K’s resurgence. Its preppy shrunken kilt-and-cropped-jumper sets were everywhere – attiring Nicole Kidman on the cover of Vanity Fair, Zendaya for Interview magazine, and Emily Ratajkowski for Vogue. Though Elsesser was also styled in the set for i-D, it was telling that the brand didn’t actually stock it in her size, and had to make one custom for the shoot.

Miu Miu wasn’t the only brand to have got the memo. Bella Hadid closed Paris Fashion Week at Coperni, where she had a dress spray-painted onto her near-naked form – a spectacle during which no one could fail to notice her protruding hip bones. Meanwhile, a new generation of models, including Lila Moss and Kaia Gerber, seem to symbolise a renaissance of the heyday of their mothers, Kate Moss and Cindy Crawford respectively.

The Kardashians – possibly the biggest tastemakers of our generation – have also slimmed down dramatically in recent months. When images emerged of Kim on James Cordon’s talk show sporting a very pronounced decolletage, fans were quick to point out a marked departure from her famously fuller figure. Indeed, the reality TV star spoke publicly about her quest to lose 16 pounds in three weeks ahead of the 2022 Met Gala in order to fit into a gown originally owned by Marilyn Monroe.

Such discussion of what is, essentially, disordered eating has become common in celebrity and influencer circles, often packaged nefariously as ‘wellness’. Gwyneth Paltrow recently told a podcast host that she typically ingests only coffee, bone broth and vegetables in a day. Those of us who remember the lexicon of ‘pro-ana’ groups will see parallels in Instagram and TikTok hashtags like #fitspo, #whatieatinaday and #bodycheck, which abound in response to statements like Paltrow's.

So, did fashion ever really shake its obsession with thinness? Or was body diversity just the latest headline-grabbing, money-making fad? And, if so, what can be done to cement meaningful change and create something less ephemeral?

There is one barrier to size inclusivity that is so simple – so fundamental – that no change seems possible without first addressing it: the simple fact that clothes are made small. Many luxury brands don’t stock higher than a UK size 14.

There is also the issue of sample sizes. To cut a long story short, models need to fit into the clothes that brands send to shoots and shows, and if those clothes are very, very small, then the models need to be very, very small. The industry standard for sample sizes is typically quoted as 34-inch chest, 24-inch waist and 34-inch hip, requiring models to be a UK size 4-6. The official reason given for this is economic: it is simply cheaper to create a collection that uses as little material as possible. It is the job of the model, therefore, to fit the clothes – not the other way around.

But many in the industry are getting tired of this damaging mindset. In 2020, stylist Fran Burns posted an image of a model wearing a pair of ill-fitting trousers by the famously skinny-centric brand Celine with the caption, 'Can we make our sample sizes bigger, please?' In 2022, she re-posted the same photo: 'It’s been nearly 18 months since I shared my feelings on sample sizing and the singular view of beauty maintained by the fashion industry. Has anything changed – not really.'

The reality is that, ultimately, the buck stops with brands. If clothes for bigger women don’t exist, then, even with all the goodwill in the world, there’s very little that casting directors can do. A lack of runway representation may then impact extended-size offerings in retailers, both at luxury brands and on the high street (which takes its cues from these aspirational houses), creating a vicious circle of exclusion and the unhealthy pursuit of thinness.

As is so often the case, it is smaller brands and younger designers that are bucking the trend – brands like SS Daley and Sinead O’Dwyer. But it should be legacy houses, with their huge resources, that bear the brunt of the financial commitment required to extend sizing. When you consider that the average size in the UK is 16, and that the plus-size market was valued at $276 billion in 2022, that they haven’t already is something of a mystery.

I’m not expecting to see many plus-size bodies on the runway this week – the world of haute couture is even more rarefied and unattainable than ready-to-wear. But I hold out hope that, in the future, diversity will be the norm rather than the exception, both on the runways and the racks.

Read more: The truth behind greenwashing in the fashion industry