Barbados or bust: the kidnapping of the Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs

During the 1,400-mile voyage to Barbados, one of the kidnappers filmed a relaxed and jovial looking Biggs on board the yacht, drinking brandy, smoking grass and even cooking dinner for the crew

Barbados, 25 March 1981. An engine splutters a bronchial, final cough and dies. The unrelenting sun, hard baked into the centre of the pellucid sky, pierces and gnaws at the pale faces of those on board the yacht; now listlessly floating, seven miles off the coast of a Caribbean paradise. Life on board is about to become infinitely less comfortable for the men now trapped on a vessel unfit for purpose.

The soft, maniacal hum of other motors begins to enter earshot. The insistent whirr of machinery, growing louder, makes the malfunctioning boat’s most famous inhabitant nauseous with simultaneous relief and fear. For Ronnie Biggs, the Great Train Robber, erstwhile British national hero to many and long-time man on the run, the next people to clamber onto the boat will either set him free, or send him home to face the wrath of an Establishment still furious at his impudence in helping to steal millions of pounds from a mail train.

As for the other men on board, in front of their eyes, their audacious plan to kidnap one of the century’s most infamous wanted men is falling apart as quickly as the engine thwarting their plans.

Less than two days previously, Ronnie Biggs was enjoying the first months of yet another year as a fugitive, drinking in the bars and walking on the beaches of Rio de Janeiro with his young son, Mike, in tow. It had now been almost 20 years since he and the fellow Great Train Robbery crew had carried out the largest heist in British history. Biggs’ role, a relatively minor one, was to locate a driver who could drive the train after the Royal Mail staff on board had been restrained. Receiving a £140,000 share of the loot for his efforts, it wasn’t long before Biggs and the rest of the gang were caught. Biggs was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Still only in his mid-30s, the prospect of staying in jail until he was a pensioner didn’t fit in with Biggs’s life plans and, barely a year after his incarceration in HMP Wandsworth, he clambered up a rope ladder over a prison wall and escaped in a waiting van. While every other member of the Great Train Robbery crew ate their porridge, Biggs remained the only known member of the gang at large; moving first to Australia under an assumed name with his wife, Charmain.

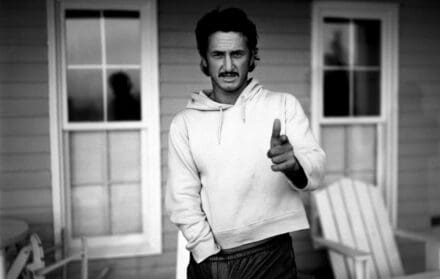

The Great Train Robber, Ronnie Biggs, sunning it up in Rio de Janeiro on 24 March 1981, the day before he was abducted

In Melbourne, a photograph published in a local newspaper in 1970 put Scotland Yard onto his whereabouts. Leaving his wife behind this time, he managed to escape to Rio, where he was able to live in complete freedom thanks to the fact that no extradition treaty existed between Brazil and the UK (a treaty was only signed in 1997).

Protected by the government in Brazil and able to make money by charging curious visitors £200 for a meeting with him, Biggs had begun to become complacent about his own security by the start of the 1980s. John Miller, a Scottish former soldier who had set up a firm supplying ex-military personnel as security for pop stars, sensed an opportunity. “It wasn’t a personal ‘I hate Ronnie Biggs’ thing,” recalled Miller, decades later. “He was a robber. I was a soldier. I was putting my expertise on the line and saying, ‘I can get this man back.’”

Believing kidnapping Biggs and taking him home to the UK to face justice would heighten the reputation of his security company, Miller had already attempted to dupe Biggs in 1979. Posing as a stuntman on Moonraker, the James Bond film which was shooting in Brazil at the time, Miller befriended Biggs and offered him a walk-on part in the movie. The ‘offer’ required Biggs to fly to Belem in northern Brazil and take a trip on a boat. Biggs would be paid £5,000 for his troubles.

But Ronnie’s luck was in. Miller tipped off a journalist about his kidnapping plan. But the hack told Biggs what was afoot and the plot was scuppered before it had begun. Two years later, Ronnie wouldn’t be quite as fortunate, mainly due to the more professional efforts of Patrick King.

Working in the shadowy world of international security, King was given a budget of £38,000 by a mysterious contact whose true identity, over 40 years on, remains unknown. This contact wanted to use Biggs as a ‘soft target’ rehearsal project which could, potentially, be used in the future to extradite perpetrators of war crimes living as fugitives in countries that didn’t have extradition treaties with the UK.

Operation Anaconda, as it was called, was underway, with King bringing in Miller and another ex-soldier called Fred Prime to assist with their new plan. There wouldn’t be so much reliance on matey inveigling this time. The plan was to snatch Biggs by force if necessary and get him to Barbados, a country that did have an extradition treaty with the UK. “It was like getting to a second Cup Final,” recalled Miller. “Except this time, we’re not going to make the same mistakes.”

In March 1981, the plan was set into action. Mark Allgate, an ex-Royal Engineer with commando training was brought onto the team, as well as Tony Marriage, an expert in surveillance. All four men had British infantry training and knew how to operate snatch squads, where ring leaders are taken out of riot situations.

Posing as a documentary team making a film about offshore oil fields, Miller and Prime set off on a yacht from Bridgetown, Barbados, heading for Belem in Brazil. King and Marriage flew on ahead of them to Rio, knowing that they had 10 days’ worth of funds from their mystery partner to find Biggs and prepare the snatch. They also knew that years in a Brazilian jail awaited them if their plans were discovered by local authorities.

“We were gonna put [Biggs] in a large canvas bag that you put marquees in,” said Miller. “It would have a sign on it that would say ‘anaconda snake – handle with care.’ We’d walk him through the departure lounge, put him on a private jet that we’d chartered, take him to the north of Brazil, put him in a yacht and sail him to Barbados. It was as simple as that.”

If they succeeded, they would have topped the efforts of Scotland Yard themselves. Seven years previously, Detective Superintendent Jack Slipper was sent to Rio after Biggs’s location was discovered by a journalist. Yet, in a worldwide sensation of a story, Biggs was given permission by the Brazilian government to stay as his girlfriend was pregnant with his child. Slipper returned home alone. Biggs, the master escapologist, retained his freedom.

Despite fears that Biggs would be wary of newcomers, the kidnapping team found cooperation with him incredibly easy. Posing as a tourist who wanted to take Biggs to lunch, Patrick King paid the obligatory £200 fee and befriended Biggs, inviting him to another meal a few evenings later, this time in a restaurant at the bottom of Sugarloaf Mountain.

With Miller, Prime and Allgate now in Rio, having flown in after leaving the yacht in Belem, the team acted quickly on the night of 16 March, running into the restaurant where a waiting Biggs managed to kick his table into the air as the team dragged him outside to a soundtrack of smashed crockery and Biggs yelling ‘help me’ in Portuguese. “Ronnie was fighting for his life. It was over in 12 and a half or 13 seconds,” recalled Fred Prime.

With tape on his face, he was bundled into the back of a van which sped towards the airfield where a £3 million private Lear jet was standing by. “That was the tricky part,” recalls Miller. “Getting an 11 stone man through departures. All anyone had to do was say ‘open the bag’ and it was over. All it would then take would be a private jet pilot saying, ‘I don’t really want your business anymore’. Then you’re truly f**ked.”

The team made it on board and flew north with Biggs remaining in the bag throughout the flight. At 1am, they landed in Belem. Biggs was now thousands of miles from Rio and had been in a marquee sack for more than four hours.

“Our transport didn’t turn up so there we were, putting a kidnapped train robber into the back of a taxi asking the driver to take us to the yacht club,” remembers Miller. Locked up for the night, the team now had to get Ronnie over a 10-foot high fence to enter the marina and take a dinghy out to the waiting yacht. “He was quite calm when we got him out of the bag,” recalls King. “I strongly sensed that he was resigned to what was happening.” During the 1,400-mile voyage to Barbados, Fred Prime filmed a relaxed and jovial looking Biggs on board the yacht, drinking brandy, smoking grass and even cooking dinner for the crew.

Miller had tipped off the British tabloids that the Great Train Robber had been kidnapped and was on his way to Barbados. But that was before the humiliation of the yachts engine failing.With all other options exhausted, the kidnappers had no option other than to put out an SOS to the Barbados mainland and be rescued, complete with their famous captive.

Thanks to Miller, the press were waiting, having flown in from all over the world to the Caribbean island, many suspecting that MI6 or Scotland Yard were the ones really behind the abduction. As the malfunctioning yacht chugged into Bridgetown harbour, it was surrounded by tiny vessels filled with photographers, hoping to get their first glimpse of a captured Biggs. “I didn’t really feel any sense of guilt at bringing him back,” recalled King. “He was a nice bloke but we had a job to do.”

Taken to the capital’s police station, the kidnap team were released on the grounds that they had committed no crimes in Barbados. Biggs, however, was handed over to the British High Commission. The Brazilian government meanwhile was outraged that somebody had been kidnapped on their soil and began proceedings to get Biggs back to Rio de Janeiro.

Over the following days, a full diplomatic conflict between Brazil and the UK blew up while, in Barbados, lawmakers struggled to figure out exactly who was behind the operation. “It was very hard for me to understand that the people who had kidnapped Biggs and taken him off the street were staying in a hotel and were free,” said Biggs’ New York defence lawyer David Neufeld. “It would, you might think, be the kidnappers who should be in the cells. They were international pirates!”

Barely three days after arriving, all the kidnappers had left Barbados with no charges bought against them. Biggs, however, was in jail, looking at being extradited back to Britain to serve the remaining 29 years of his sentence for his part in the Great Train Robbery. “He didn’t seem unduly worried. He seemed to believe that fate would play a part in the injustice being righted. I can tell you, at that stage, I wasn’t that hopeful,” said Ezra Alleyne, one of Biggs’s defence team.

The prosecution argued that Biggs’s extradition was essential as a lesson to other members of the criminal underworld that their crimes wouldn’t go unpunished. Biggs, it seemed, was certain to be taken home to a British prison cell. But then, in an unbelievable twist, Alleyne discovered that the extradition treaty with Britain had not been properly validated in the Barbados parliament.

On 23 April, Neufeld and Alleyne made their case to the magistrate that the treaty wasn’t legal. The court, their hands tied by legal protocol, had no choice but to let Biggs go. “It was pandemonium outside the court,” remembers Alleyne. Borne aloft by a huge crowd, the Houdini of the criminal world had, miraculously, evaded British justice once again. Two TV companies stumped up the cash for a private jet to fly Biggs back to Rio to be reconciled with his son. Biggs was filmed kissing the tarmac at Rio airport when he alighted from the plane.

As for the kidnappers, their failure to get Biggs back to Britain didn’t unduly affect their confidence. “I wasn’t worried one way or the other,” reflected Miller. “We achieved our objective. If he got away with it [in the courts] then good luck to him.” Miller’s final role in the kidnap was to sell a fake picture of Biggs being kidnapped to the Sunday Mirror. In fact, the man in the bag was his co-accomplice Fred Prime. Miller went on to manage a country and western club in the States and even sold another fake story to the press claiming he’d met Lord Lucan.

For Biggs, the money started flowing in again with his new, enhanced celebrity status back in Brazil; a situation that continued right up until 2001 when he finally gave himself up after a series of strokes. He returned voluntarily to the UK to serve time in Belmarsh High Security prison before dying, aged 84, in December 2013.

Four decades on, crucial questions about the case remain unanswered. Why were charges never brought against the kidnapping team? And why was there never an inquiry to find out exactly who King’s mystery sponsor was and where the funds to enact Operation Anaconda had came from? “I think, if it had been successful, then the true source of who was behind this would have come forward,” said Biggs’s lawyer David Neufeld. “But it wasn’t. And we still don’t know.”

Read more: How the Manson Family cult continued after its leader was behind bars