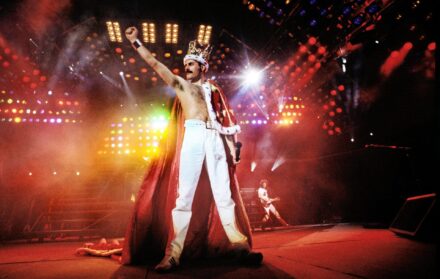

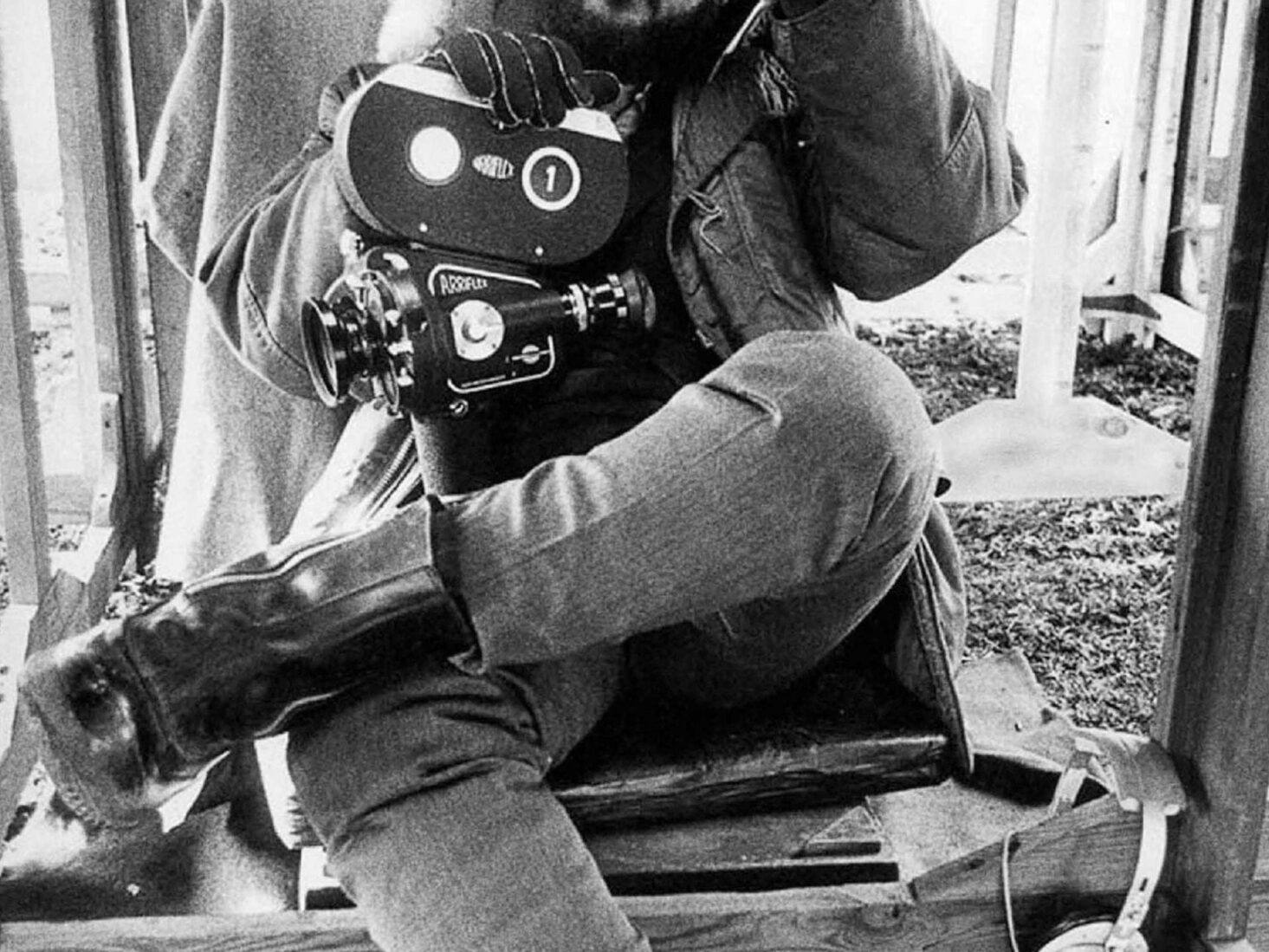

Why Stanley Kubrick’sAClockwork OrangeWasn’t Shown in the UK for Three Decades

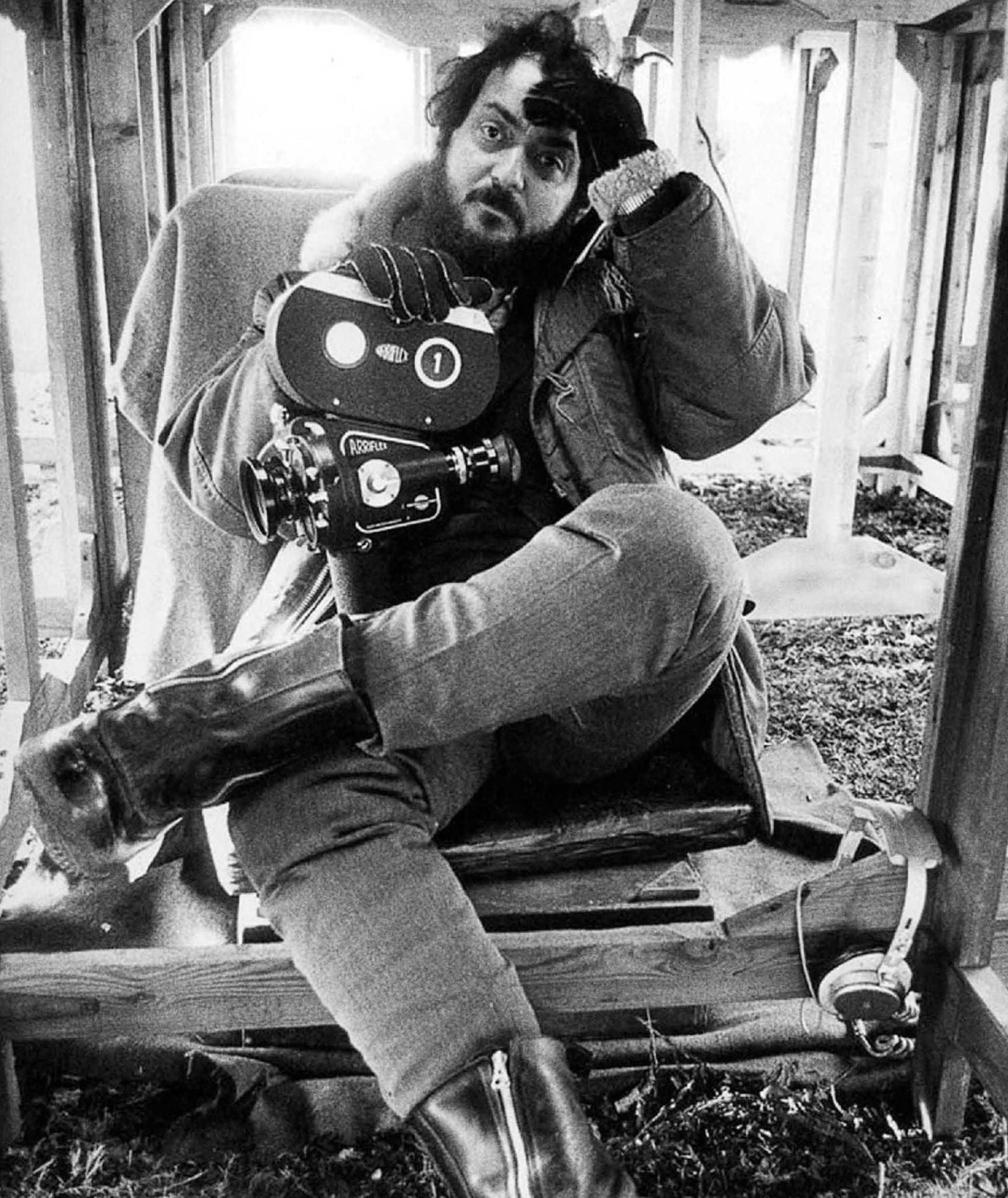

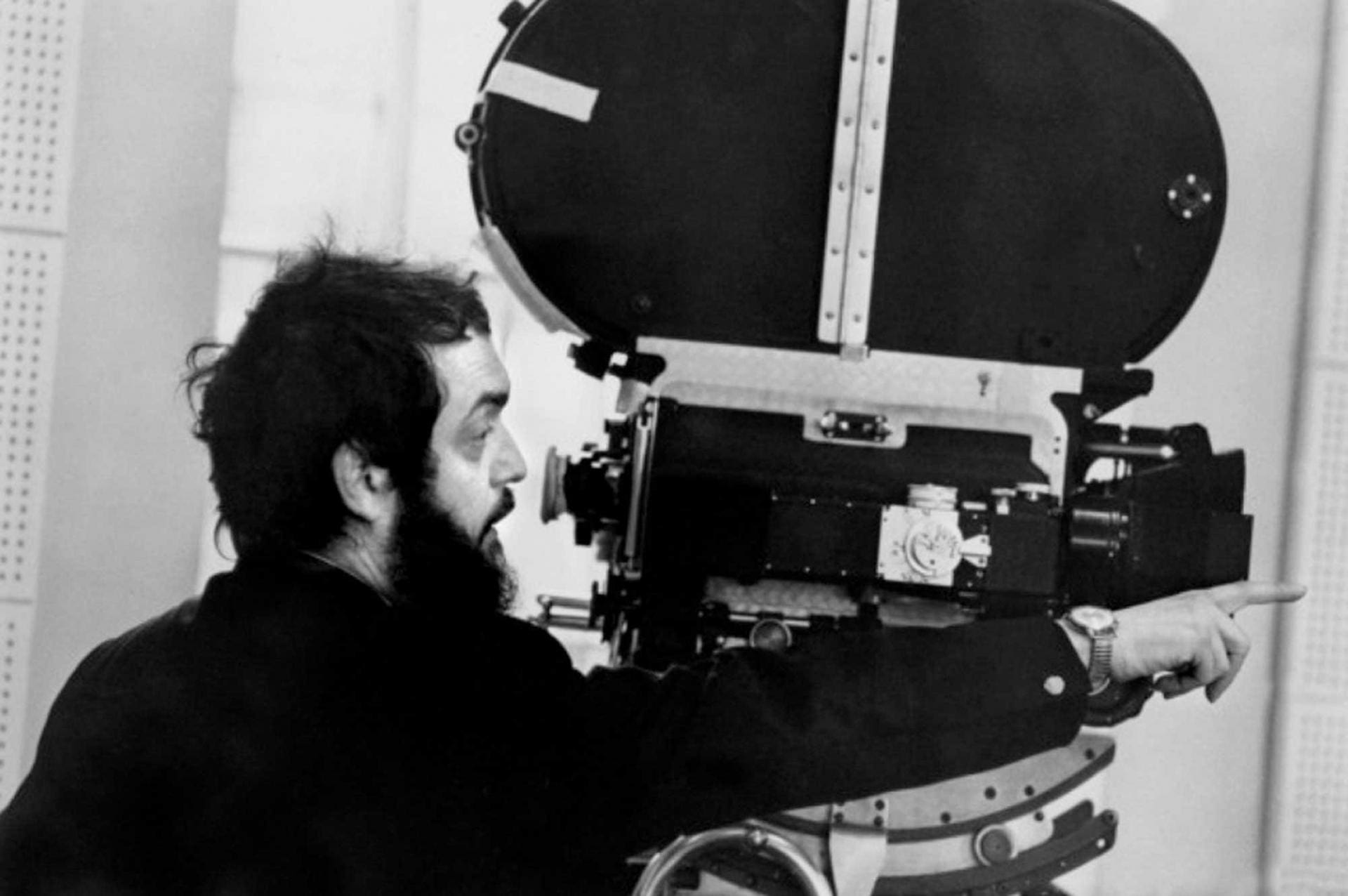

As a major retrospective of Stanley Kubrick opens at the Design Museum, Luxury London explores the events that meant one of his most iconic films couldn't be seen in the UK for nearly three decades

‘Being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultra-violence and Beethoven.’ So ran the strap-line at the top of the poster for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, released in British cinemas in the freezing depths of January 1972.

Introducing audiences to a world of ‘deng’ (money), ‘milk plus’ (milk laced with drugs), ‘veks’ (men) and ‘devotchkas’ (girls) – all part of the dialect of ‘Nadsat’ spoken by the main characters – the adaption of Anthony Burgess’ novel showed a dystopian Britain of the near future. Immorality and free will are blamed for society’s ills and the thuggish teenage protagonist Alex DeLarge is subjected to radical brainwashing techniques designed to make him ‘good’.

The film sent both critics and audiences into a frenzy. The highly stylised violence led Roger Ebert in the The New York Times to brand the film an ‘ideological mess’ while Pauline Kael in the The New Yorker called it merely ‘pornographic’. The rancour even triggered politicians to wade in, with Labour MP for Coventry West Maurice Edelman predicting in a newspaper interview that “when Clockwork Orange is released, it will lead to a ‘Clockwork cult’ which will magnify teenage violence”.

While critics and politicians debated the meanings and nuance of the film, in suburban parts of the UK tales of a more visceral nature emerged. Throughout 1972, newspapers feasted on stories concerning supposed copy-cat gangs who, in the manner of DeLaerge and his ‘droogs’ (friends), would run riot, assaulting, raping and engaging in their own bouts of ‘ultra-violence’.

Rarely, however, did these stories stand up to even moderate rigour. Richard Palmer, a 16-year-old from Bletchley, went on trial for the murder of a tramp, a scenario that famously appears in one of the film’s first scenes. The media furore began when a consultant psychiatrist testified that Palmer was “acting a part very similar to the characterisations given by A Clockwork Orange”. The Daily Mail wrote a story concerning the ‘Clockwork Orange boy’, ignoring the fact that Palmer, being underage for an X-certificate film (today’s 18 rating) hadn’t actually seen the movie at all but had merely been told about it by friends.

Meanwhile in Lancashire, a 17-year-old holidaying Dutch girl was raped by a gang of youths who, according to reports, sang ‘Singing in the Rain’, another apparent replica of one of the film’s most notorious scenes.

By 1973, almost any violent crime committed by youths seemed to be attributed to the film. Mike Purdy who worked as a solicitor for the Metropolitan Police later recalled: “At the Old Bailey we kept seeing people on assault charges who had seen the film and been impelled to go out and beat someone up. Most of us who worked at the court thought this a load of rubbish but unfortunately such cases got a lot of publicity and many judges would impose lesser sentences in these cases.

“It got to the stage when we referred to these cases as ‘Clockwork Orange defences’ and it became almost boring as one after another tried using this excuse.” Many judges felt differently. One judge, after sentencing a 16-year-old for beating a younger child while dressed in the droog’s uniform of white overalls and a bowler hat, stated that the crime was part of a “horrible trend which has been inspired by this wretched film”.

The famously reclusive Kubrick, faced with protests taking place outside the front door of his home, gave an elegant riposte to the mounting barrage of criticism in an interview with film critic Michel Ciment, first published in the French film magazine Positif. “I know there are well-intentioned people who sincerely believe that films and TV contribute to violence,” he argued, “but almost all of the official studies of this question have concluded that there is no evidence to support this view. At the same time, I think the media tend to exploit the issue because it allows them to display and discuss the so-called harmful things from a lofty position of moral superiority.”

It wasn’t just the media that felt the wrath of Kubrick. The English judicial system was, for him, equally erroneous.“The simplistic notion that films and TV can transform an otherwise innocent and good person into a criminal has strong overtones of the Salem witch trials. This notion is further encouraged by the criminals and their lawyers who hope for mitigation through this excuse.”

What came next has been widely misunderstood. The noun most commonly associated with A Clockwork Orange is ‘banned’ though this was never actually the case. Despite his robust written defence of A Clockwork Orange, it was Kubrick himself who instructed that the film be withdrawn from circulation in the UK in 1973 (it could still be seen anywhere else in the world) and continued to refuse any screenings of the movie up until his death in 1999.

And so, for teenagers of the 70s, 80s and 90s, A Clockwork Orange developed an entire cult of its own as ‘the movie you couldn’t see’.

The fact that Kubrick’s withdrawal of the film only applied in the UK meant that cinemas in Amsterdam made a handsome trade offering screenings of the film 24-hours-a-day to curious British tourists. And, in the era of the bootleg VHS videotape, numerous black and white copies, which varied hugely in quality, did the rounds of university halls of residences and ‘under-the-counter’ video rental shops across the UK.

Why Kubrick maintained his position on the film up until his death is a matter of pure conjecture. He never spoke about it – yet his actions on the matter were perhaps indicative of his stubborn character. In 1983, the Scala Cinema in Kings Cross went out of business after losing a legal battle with Warner Bros, launched at Kubrick’s insistence, when the cinema held an unauthorised screening of the film.

Perhaps Kubrick was right to be so intransigent. In recent years his widow, Christiane Kubrick, has spoken of death threats against the family as the controversy surrounding the film intensified in 1972. Julian Senior, the vice-president of European Advertising and Publicity at Warner Bros at the time of the film’s release, later stated in an interview with The Guardian that: “the police were saying to us, ‘We think you should do something about this. It is getting dangerous.’”

Now, nearly half a century on from the film’s release, questions are still being asked about A Clockwork Orange. It was re-released in March 2000 in UK cinemas after a 27-year absence, and the reaction from critics and first-time viewers was mostly that of mere curiosity and relief to finally view a slice of cinematic history long stripped of its supposed power to incite real-life horrors.

Yet, although the graphic violence may no longer shock us as it did in 1972, the film continues to ask questions of us. Is the film still a social prophecy of our future? Where does the gap between entertainment and moral responsibility for a director lie? Is there any real difference between a ‘clockwork’ obedience to the state and a mind mechanised towards violence and the self? And, perhaps most pertinently, how culpable are we, the audience, for the more degenerate elements of society if we continue to watch films which expose and explore the more nefarious elements of human nature?

As Kubrick himself wrote: “To try and fasten any responsibility on art as the cause of life seems to me to put the case the wrong way around. Art consists of reshaping life, but it does not create life, nor cause life.”

Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition (£16) runs from 26 April to 17 September at the Design Museum, Kensington High Street, designmuseum.org