The 50-year tangle of Marlon Brando’s ‘Last Tango in Paris’

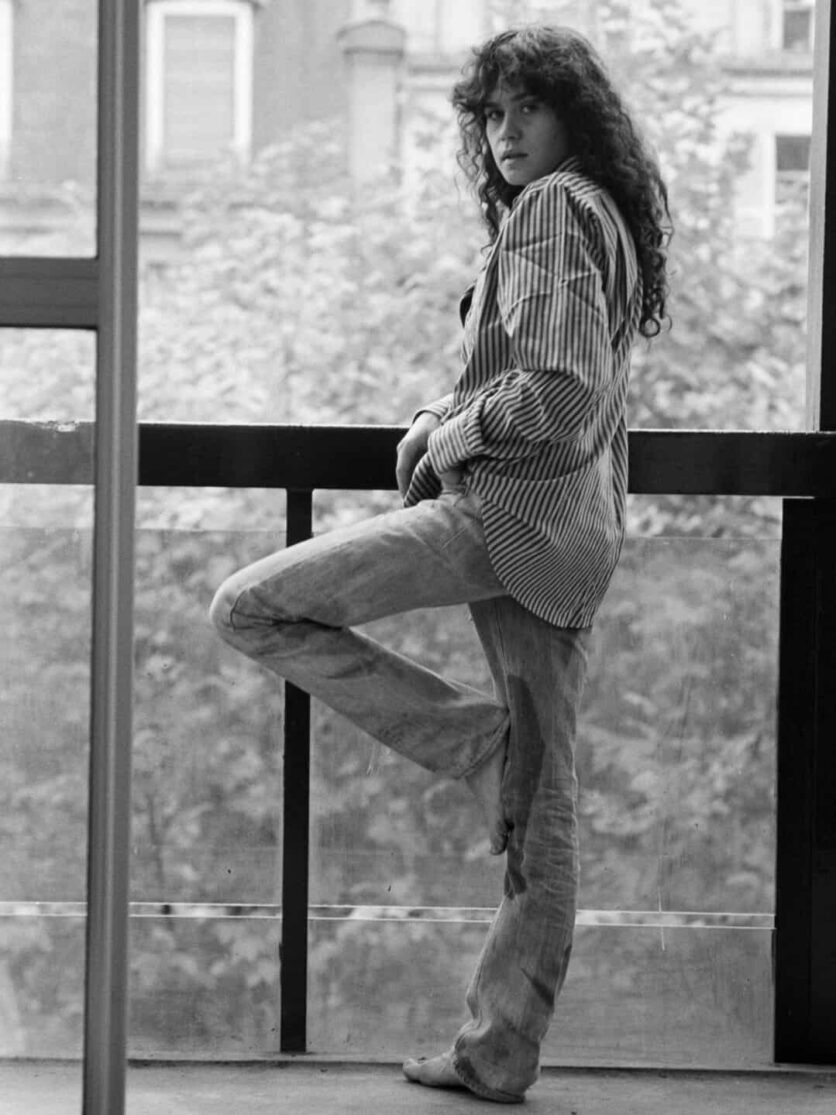

Half a century after its release, a new series sets out to explore the notorious production of Marlon Brando’s 'Last Tango in Paris' from the perspective of his 19-year-old co-star, Maria Schneider

Jeanne: Why do you hate women?

Paul: Because either they always pretend to know who I am, or they pretend I don’t know who they are, and that’s very boring.

*

Paris in the early 1970s. Brown, severe, tired, ashen. A place where austerity had waged a rancorous, and victorious, war over innocence and beauty. In thrall to the intellectual nihilism of Beckett, Sartre and Camus, the French capital was mired in a fug of cigarette smoke, existential philosophy and ennui as grey and unremitting as the flow of the Seine. The City of Light. Never had a moniker rang so vacantly.

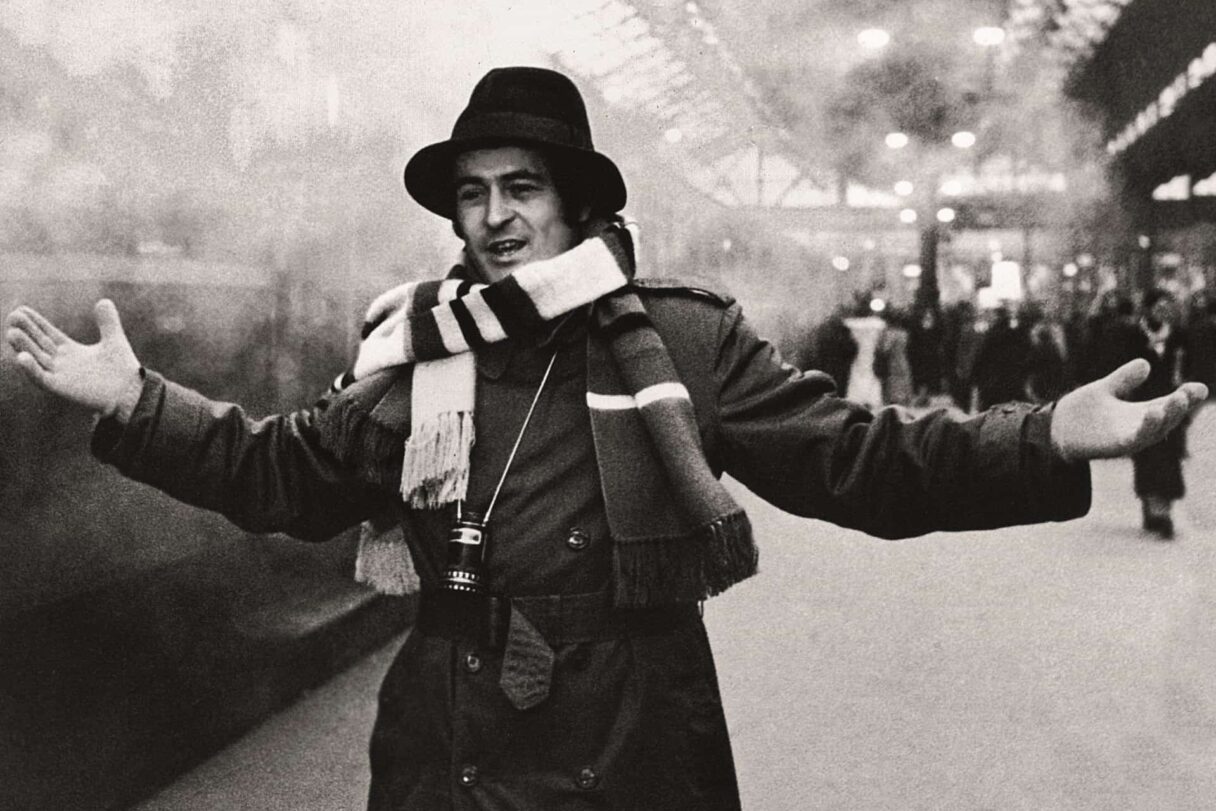

It was also, if we are to believe the Paris created by director Bernardo Bertolucci in 1972, a place where broken men were free to destroy younger women. A way to rage against and further nullify their own ravaged lives, we’re invited to believe. Such is the wont of Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris, who played 45-year-old widower Paul to the 19-year-old actress Maria Schneider, who was cast as the aspiring actress Jeanne.

The two meet when searching for an apartment on Rue Jules Verne. They use the apartment for sex, which is animalistic, a retreat from the city outside. At no point, at Paul’s insistence, do the two ever reveal their names to each other. Jeanne is a smear of beauty against a backdrop of dereliction and decay. Far from non, je ne regrette rien, the Paris of 31-year-old Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci is a city that appears to regret everything. From the bottle of pastis last night, to the street battles of the previous decade.

When explaining how he wanted the film to look, Bertolucci took the film’s cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro, and, later, Brando himself, to see an exhibition of Francis Bacon paintings; two of which are displayed in the film’s opening credits. The wasted figure depicted in Portrait of Lucian Freud encompassed the brown colours, the despair, the suffering, for which Bertolucci was aiming.

“You see that painting?” the director is said to have asked Brando. “Well, I want you to re-create that same intense pain.” Bertolucci would later say: “That was virtually the only direction I gave him on the film.”

At its most prosaic level, Last Tango in Paris explores how the cynicism and sexual demands of an ageing Lothario are surmounted by a far younger, much more impetuous woman. The strength of Schneider’s performance, however, and the power of the film in general, has been seriously tainted by later revelations.

At the time, Pauline Kael, then possibly the world’s pre-eminent film critic, wrote in The New Yorker that Last Tango in Paris had the ‘same kind of hypnotic excitement as Sacre [a reference to the debut performance of Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring in Paris, which caused the audience to riot in 1913]… the same primitive force, and the same thrusting, jabbing eroticism.’

Kael went on: ‘Tango has altered the face of an art form. This is a movie people will be arguing about for as long as there are movies.’ To Kael, Tango was ‘the most powerfully erotic movie ever made, and it may turn out to be the most liberating movie ever made.’ This, from a female critic who had just witnessed a scene in which Paul rapes Jeanne in the apartment, using butter as a lubricant. As it later emerged, the pain on Jeanne’s face as she is abused was not purely theatrical.

Upon Tango’s release in Italy in December 1972, there were few showings, censors having refused to officially pass the film. That didn’t prevent the film grossing an unprecedented $100,000 in its first six days, with some cinema-goers reportedly offering up to $100 per ticket. In 1976, the Italian Supreme Court ordered all copies of Tango to be destroyed. Bertolucci was given a four-month suspended prison sentence and banned from voting for five years.

In France, where Tango received critical acclaim, filmgoers queued for two hours. To get around censorship in their home country, Spaniards crossed the border into France. The film’s 1973 US release prompted cover stories in both Time and Newsweek magazines. The weight of contemporary censors’ condemnation, and subsequent criticism, centred on the rape scene, a scene that critics like Kael chose largely to ignore, fixating instead upon the eroticism of Tango’s numerous other sex scenes.

“I should have called my agent, or had my lawyer come to the set because you can’t force someone to do something that isn’t in the script,” Schneider said of the scene during an interview in 2007. “But at the time, I didn’t know that… Even though what Marlon was doing wasn’t real, I was crying real tears… I was too young to know better. Marlon later said that he felt manipulated – and he was Marlon Brando – so you can imagine how I felt. People thought I was like the girl in the movie, but that wasn’t me.”

In 2007, Schneider’s comments failed to ignite a serious reassessment of the film. In the wake of #MeToo, however, it’s become almost impossible to watch Tango through anything other than the prism created by her admission. Schneider died in 2011, aged just 58. Leading Hollywood stars, including Chris Evans and Jessica Chastain, have subsequently taken to Twitter to rage against Tango, the latter tweeting, ‘To all the people that love this film, you’re watching a 19-year-old get raped by a 48-year-old man. The director planned her attack. I feel sick.’

Bertolucci, before his death in 2018, insisted that the entire scene was in the script, and that Schneider knew what was going to happen during filming. Schneider, Brando and Bertolucci all agreed that there was no actual rape, with the director saying that the only improvised part was the use of the butter. That, in itself, was enough for Bertolucci to admit to feelings of shame about his treatment of Schneider.

“I’ve been, in a way, horrible to Maria because I didn’t tell her what was going on, because I wanted her reaction as a girl, not as an actress,” Bertolucci said in a 2013 TV interview. “I wanted her to react humiliated... And I think that she hated me, and also Marlon, because we didn’t tell her [about the butter]… and I still feel very guilty for that.”

Schneider remained friends with Brando until his death in 2004, but she never spoke to Bertolucci after filming was finished. With both actors and director having passed away, there can be no further questioning of the participants or the victim. What is undoubtedly clear, is that abuse of female actors by powerful men has a long and miserable history in Hollywood.

From the treatment of Shelley Duvall by Stanley Kubrick during the making of The Shining – when his bullying caused the actress’ hair to fall out – to Alfred Hitchcock’s harassment of Tippi Hedren during The Birds – which saw the director throw live birds at her until she had a nervous breakdown (Hedren had refused to sleep with Hitchcock during shooting) – right up to the treatment of female actors by Harvey Weinstein. Can abuse factor in the creation of great art? Undoubtedly. Whether non-consensual behaviour should play a part in the creative process is a question that, two generations on from Last Tango in Paris, has shifted from the ambiguous to the definitive. No.

We would like to think that there is next to no possibility of a contemporary actor having to endure what Maria Schneider went through during the filming of Last Tango. An overdue array of protective measures aims to ensure that artists are in control during every step of the filming process. Back in 1973, however, it seems an actor giving in to the degrading directorial whims of a filmmaker like Bertolucci was something of a Faustian pact. Quite rightly, it has brought Bertolucci posthumous infamy.

Last Tango in Paris stands as a half-century-old celluloid document that has helped prompt two successive sexual revolutions. The first, upon release, was one of sexual liberation and euphoria among viewers. The second, after the death of Brando and Schneider, came from a re-positioning of the film’s perceived intentions and expositions.

Far from a tale of ennui, despair and sexual escapism, the film no longer resides in retro Parisian aspic, but serves as a cautionary tale as to what happens when artistic freedom reaches its absolute limits, evolving from emancipation into entrapment and coercion.

The sex, the décor, the clothes, the city of Paris of 1973 may now feel dated. But the conversations, explorations and progressions triggered by Last Tango in Paris continue to advance. In the truest, most enlightened sense of that great cliché, this is a film that could never be made today.

America’s CBS Studios is co-producing Tango, a limited series that will explore the 18 months before, during and after the making of Last Tango in Paris.