Tom Parker: The scandalous story of Elvis Presley and the illegal Dutchman

Colonel Tom Parker is the most controversial huckster in showbiz history. To mark the release of Baz Luhrmann's biopic Elvis, which sees Parker played by Tom Hanks, Luxury London explores the bizarre life of Elvis Presley's manager and

If you happened to be on the gaming floors of the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas during the early-to-mid 1970s, there’s a strong chance that, no matter what time of day or night you entered, you’d spot a six-foot-tall, grossly overweight man in front of the roulette table. With an elephant-head cane resting by his side, a cigar clamped into his mouth and a cheap baseball cap sat awkwardly on his huge bald dome, this man was, with a grim determination, seemingly going out of his way to lose incredibly large sums of money.

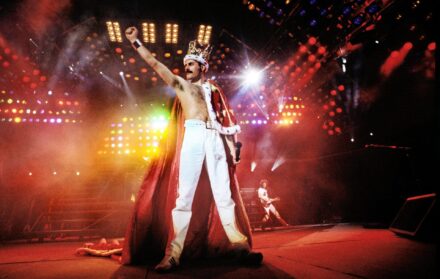

There were more than a few men who would have roughly fitted this description in Nevada half a century ago. But this gambler was far from a day-tripper to the casino. He considered the roulette wheels and the craps tables to be his “other office”, spending, at times, 12-14 hours a day there. His actual office was located on the fourth floor of the same building. Occupying a suite of rooms, the hub of Colonel Tom Parker’s operation looked like the concession stand of a particularly cheap and tawdry travelling fairground. Paper hats, glossy posters, souvenir programmes and gaudy key rings covered the room from top to bottom. But the memorabilia wasn’t for a rodeo or travelling circus. It was for the greatest showman in rock ‘n’ roll history: Elvis Presley, aka ‘The King’.

Played by Tom Hanks in the new biopic Elvis, directed by Baz Luhrmann, Colonel Tom Parker remains, 25 years after his death, and nearly half a century after the death of his only client, the most memorable and divisive manager in the history of show business. It was the Colonel who propelled his “boy”, as he would refer to him, from being a local celebrity in Memphis to being the most famous and successful performer on the planet.

But the Colonel was also the man who most hold responsible for Elvis’ stagnant years making appalling movies in Hollywood. He’s also held culpable as the man whose gambling addiction and debts to Vegas casinos contributed to Presley being forced to spend years in an unending cycle of matinee and midnight shows which slowly wrecked his creativity, and then his body.

It was only after Elvis’ untimely death in the bathroom of his Graceland home in August 1977 at the age of just 42 that the truth emerged about this P.T. Barnum-esque character who transferred his skills in hucksterism and cunning from the travelling carnivals to the biggest stages on earth. Almost everything about the Colonel was a fabrication. His name wasn’t Tom Parker and he certainly wasn’t a military colonel, merely an honorary one who was given the title by the governor of Louisiana.

Parker always claimed he was from West Virginia, but, three years after Elvis’ death, it emerged that the man who managed The King was actually born Andreas Cornelis Dries van Kuijk in Breda, the Netherlands, in 1909. Stowing away on a cruise liner to the States in 1929, the Colonel lived for decades in fear of being discovered as an illegal alien. Despite his lack of papers, Parker managed to enlist in the US Army, although he then went AWOL and was imprisoned briefly for desertion in 1932. It was only after this unhappy period that the Colonel found his natural home, working in travelling carnivals that toured the American South.

He adored telling his old ‘carny’ conman stories. He would paint sparrows yellow and sell them as canaries. He sold hot dogs that had no ‘dog’ at all in the middle. He even put chicken feed onto a hot wax cylinder and charged people to watch his ‘dancing chickens’ as the animals would jump on their blistered talons attempting to peck at the food.

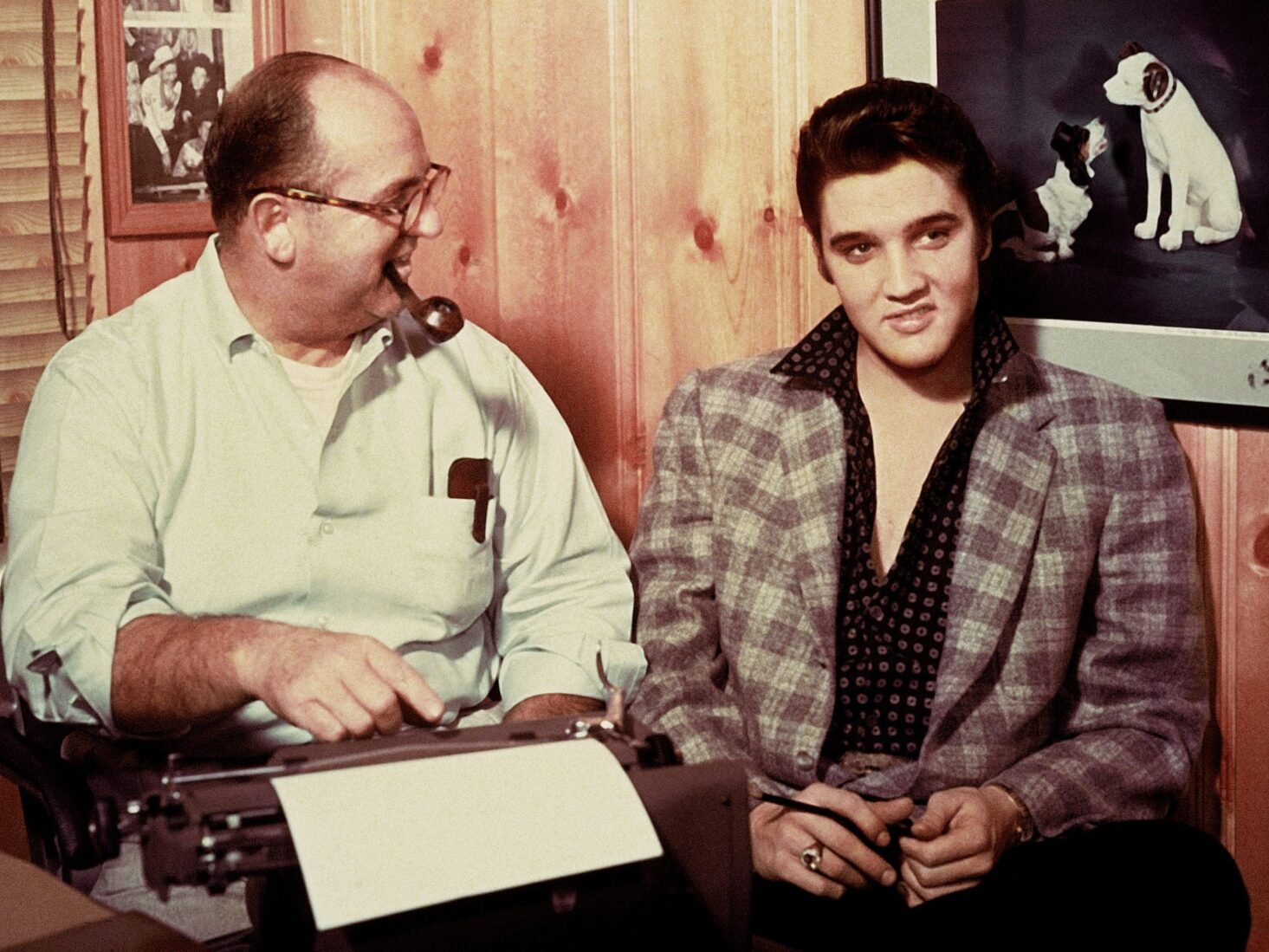

Many of the travelling carnivals of the 1940s and 1950s had musicians as part of the caravan and the Colonel began his managerial career by looking after now-long-forgotten country singers, including Eddy Arnold and Gene Austin. Signing a boy called Elvis Presley from Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1955 was the beginning of a working relationship that would last continuously until The King’s death.

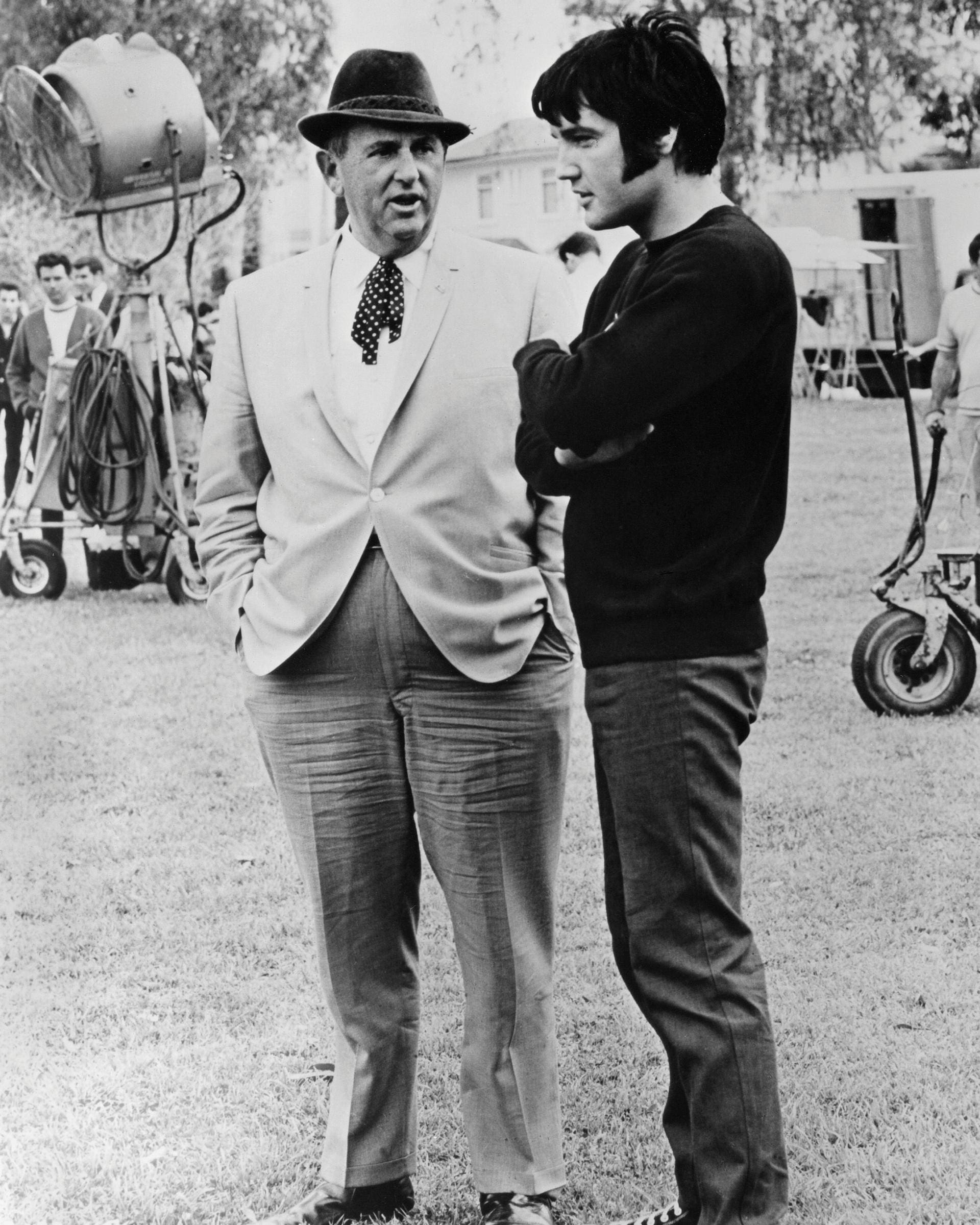

There’s no doubt that the Colonel worked wonders in negotiating hard bargains for his client, getting him signed to RCA Records, maximising the financial returns and keeping Elvis’ name in the spotlight, even when the singer was drafted into the US army and unable to record for two years. Yet Elvis’ decline in the 1960s into increasingly embarrassing movies prompted the beginning of a conflict that would result in the two men being barely on speaking terms by the time of the entertainer’s death.

Elvis’ films always made money, despite their wretched quality. This, as far as the Colonel was concerned, was the bottom line. But for Elvis, a creative artist who knew The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Beach Boys were making him seem an archaic irrelevance by the mid-60s, the desire to rediscover himself as a musician, not a middling actor, led to increasingly bitter disputes with his manager. Grudgingly agreeing to arrange Elvis’ eventual return to the stage in Las Vegas in 1969, the colossal success of his early comeback shows in the desert prompted Presley to push the Colonel to plan a world tour, something he had wanted to do for years.

But the Colonel made an art form out of creating excuses. Citing everything from ‘security’ when an offer came in to tour Japan, to claiming that there were no stadiums big enough overseas to host an Elvis concert, he succeeded in batting off every invitation, all to Elvis’ intense irritation.

It’s clear that Parker feared not being allowed back into the States should he ever leave the country. What remains a partial mystery is why, with the Colonel’s incredible collection of contacts, he didn’t come clean and simply attempt to sort out his citizenship. He counted President Lyndon Johnson among his personal friends. So it would appear that some discreet behind-the-scenes negotiations could have resolved the problem without too much fuss.

One reason why the Colonel didn’t do so is theorised by his biographer, Alanna Nash. She suggests the possibility that the Colonel’s evasions were due to a murder he committed in the Netherlands, which prompted his hasty departure across the Atlantic. But this allegation is based on nothing more than an anonymous letter accusing Parker of killing a greengrocer’s wife 50 years prior. The letter offers no evidence or first-hand knowledge of events, and the man who received the missive, a Dutch journalist named Dirk Vellenga, didn’t even mention it in his own book on Elvis and the Colonel. It’s possible that Parker could have known the victim and been familiar with the Dutch neighbourhood where the killing took place. But beyond this, in true Parker style, there is nothing more solid than cigar smoke at which to grasp.

During the 1970s, as The King tired of the repetition of his Vegas engagements and descended ever deeper into prescription drug addiction, a new routine emerged. Elvis would sleep for the day in his penthouse suite, while down on the gaming floor the Colonel would be steadily increasing his losses at the craps table and the roulette wheel.

“Colonel Parker was probably one of the most degenerate gamblers I have ever known in my life,” said Lamar Fike, a member of Elvis’ notorious Memphis Mafia group of friends and hangers-on. “In Nevada they used to say that his money wasn’t worth anything. In a period of an hour-and-a-half I saw him lose over a million and a quarter [dollars]”. It was, in part, the money that the Colonel owed the casinos which ensured that Elvis would continue playing Vegas right up until the end of 1976, just eight months before his death.

The Colonel outlived his sole client by 20 years and remained bullish and typically frustrating as an interview subject right until the end. “I don’t think I exploited Elvis as much as he’s being exploited today,” was one comment he made in an interview in 1980, which perhaps came closest to an admission that his management style might not have utilised his client’s immense talent to its fullest potential. Yet Elvis himself, for reasons that have never become entirely clear, failed to find the courage to fire the Colonel. Sued by the Presley estate for fraud in 1983, six years after The King’s death, and evicted from his suite in 1984, Parker continued to live and work in Vegas as a consultant for Hilton Hotels until a fatal stroke in 1997.

By the time of Elvis’ death, the Colonel was said to owe the Hilton Hotel group around $30 million in gambling debts. After his own death, the Colonel’s estate was worth barely $1 million, despite most estimates putting Parker’s earnings during his lifetime as being in excess of $100 million. Ultimately, the shrewdness of the business deals that Parker negotiated for Elvis were entirely in vain. Despite taking 50 per cent of all the profits from Elvis’ career, Parker was no less gullible than the ‘rubes’ whom he delighted in exploiting in his carnival days. The Colonel himself ended up being the greatest sucker of them all, giving back almost his entire fortune to the Hilton croupiers.

Whatever it was that forced Andreas Cornelis Dries van Kuijk to flee the Netherlands, never making contact with his mother and father again, it was something that he did not want to talk about. Yet whenever the Colonel was asked about his treatment of Elvis, he was always ready to reply with the same response. He would snarl, stamp his cane, and repeat his time-worn reply: “I sleep good at night.”