Hunter in the jungle: How Hunter S. Thompson screwed up the fight of the century

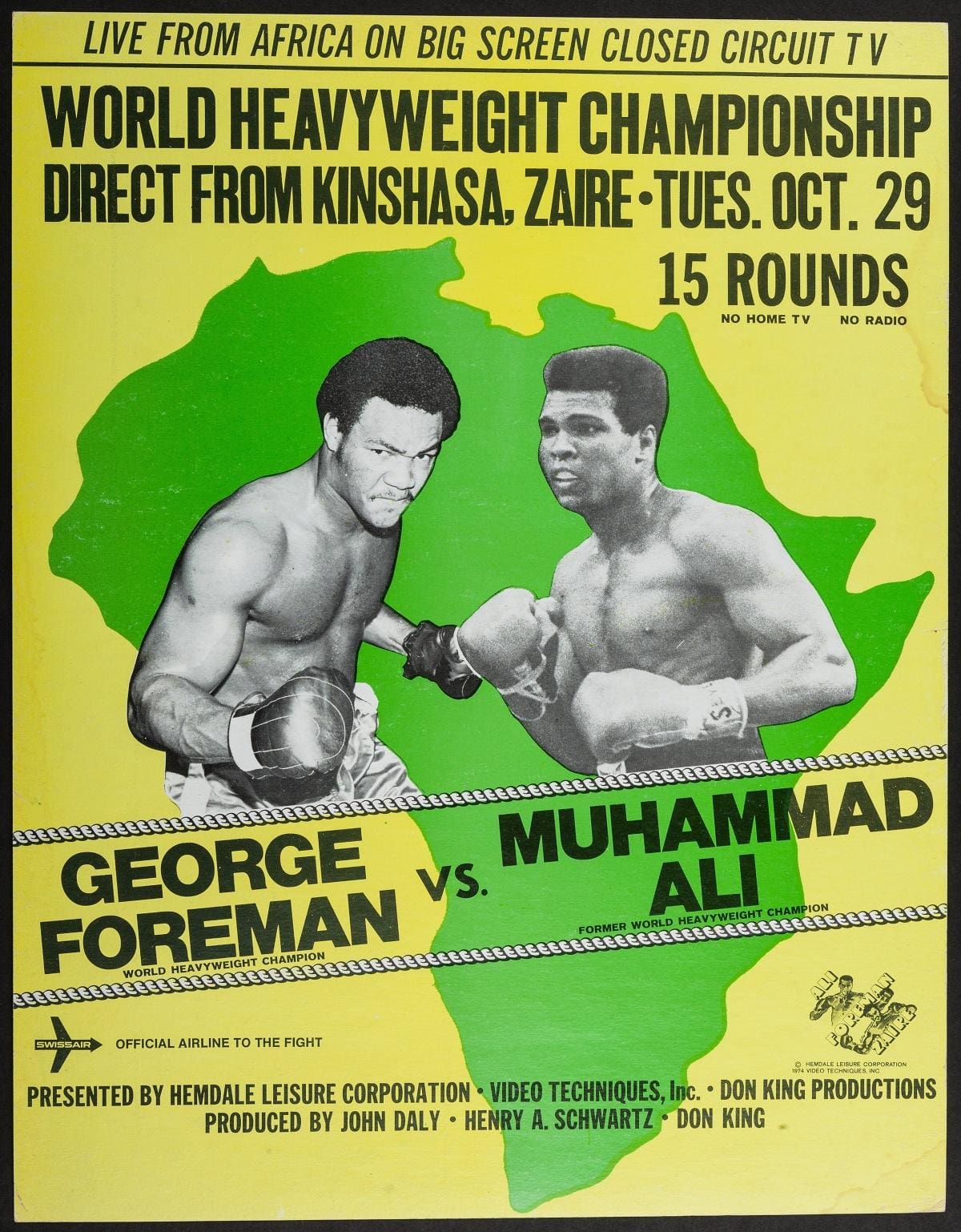

For Thompson, deployed to cover the fight for Rolling Stone, everything seemed in place for this to become one of his most celebrated pieces of writing; the enfant-terrible of American counter-culture, travelling to the heart of Africa

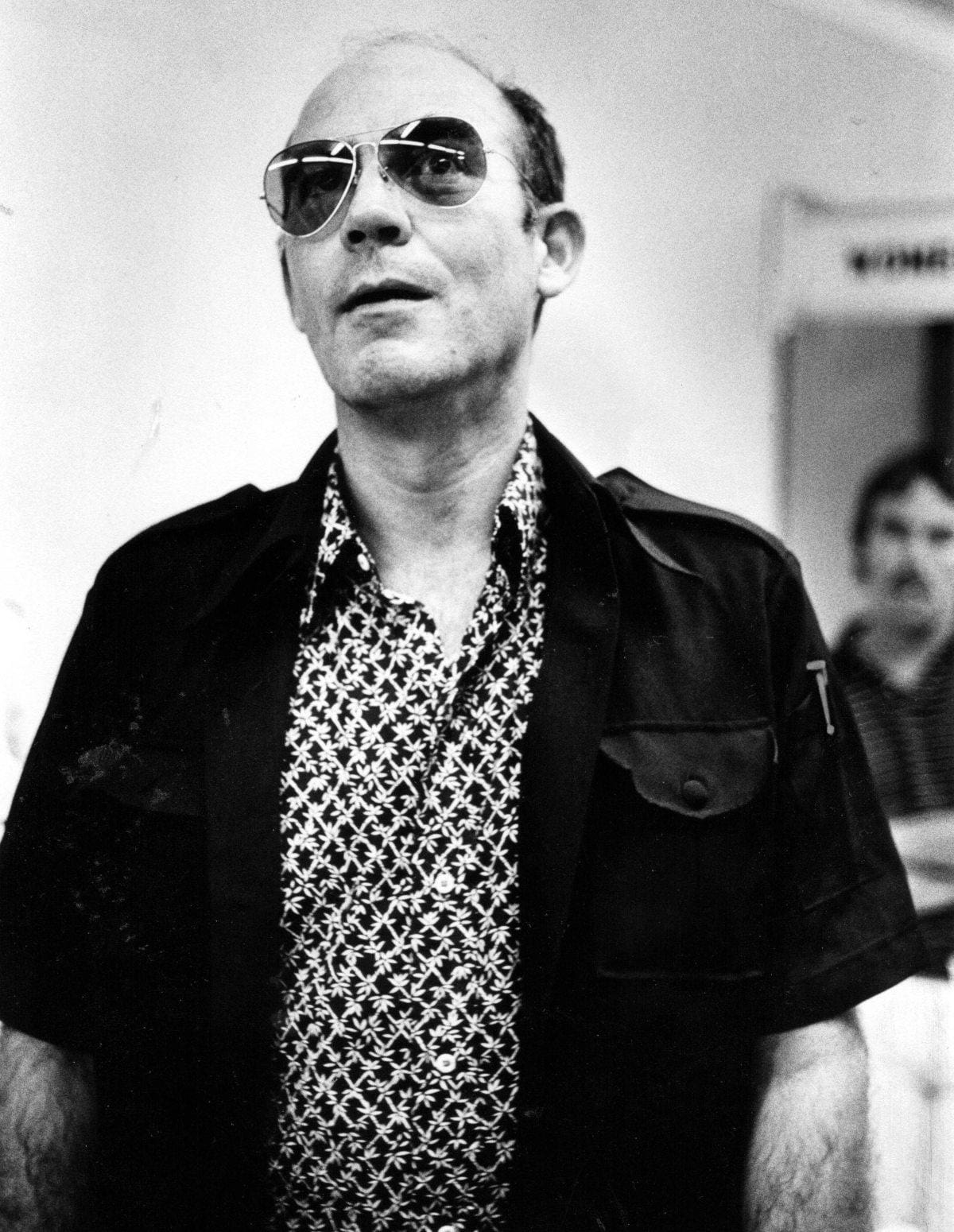

Early morning in Africa and Hunter S. Thompson is floating motionlessly towards the edge of a swimming pool. Cigarette smoke emanates from his mouth, swirling up into a soot-black sky unilluminated except for an intense floodlit glow a few miles beyond the fence of the hotel complex. This man is a sportswriter. A journalist. A champion of civil liberties. A Herculean drug taker and an individual already spoken of in his home country as being one of the most incendiary, vital authors and reporters of his generation.

This was supposed to be the highpoint of his career. A moment when the most pugilistic of writers mixes it with the greatest athlete of the century. But in the dead of night, in a Kinshasa swimming pool, Hunter S. Thompson blew everything just as Muhammad Ali confirmed himself as one of the finest heavyweight boxers the world would ever see. It could so easily have been so very different.

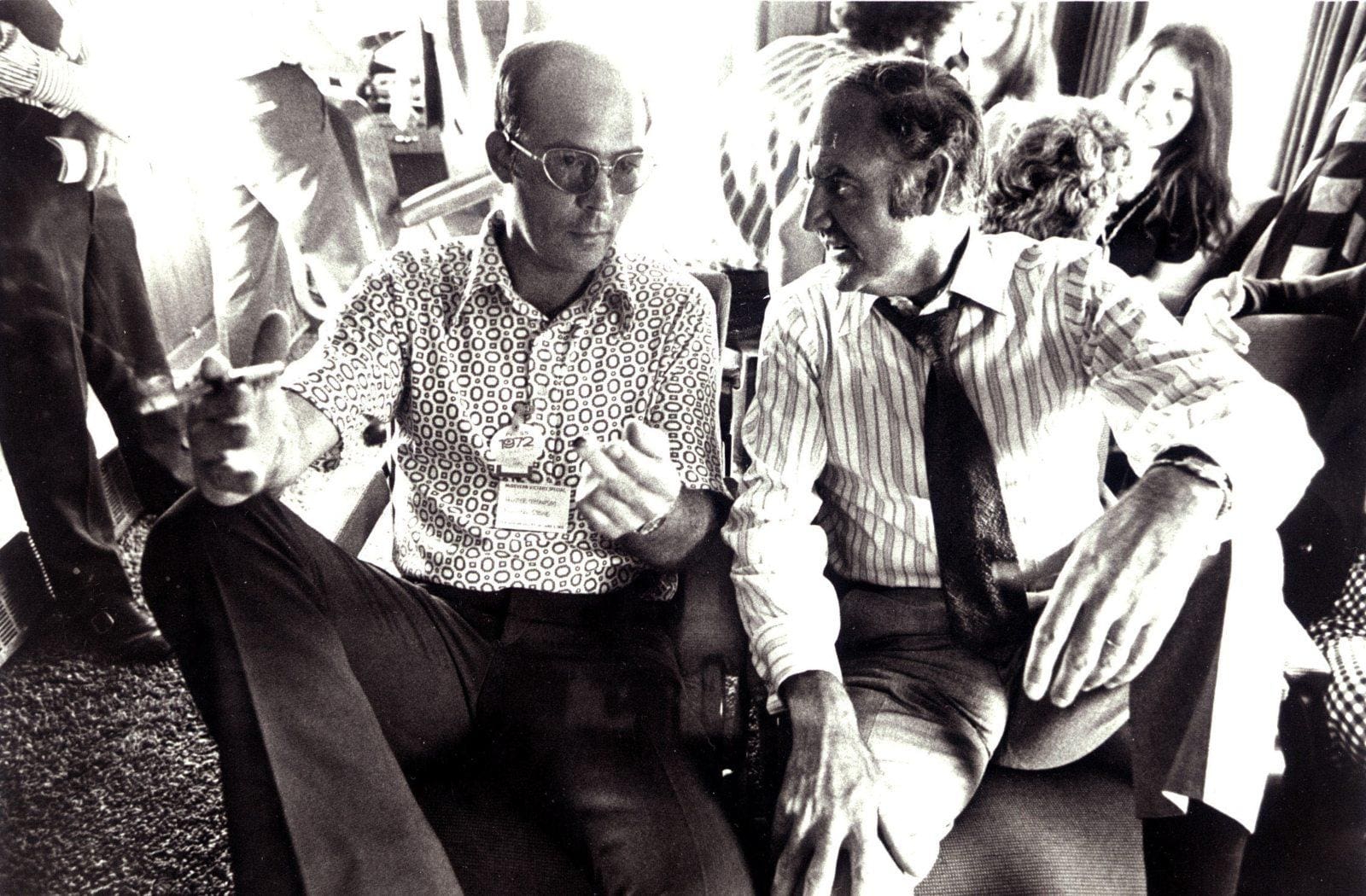

Hunter’s frenetic, free-wheeling journalism for Rolling Stone magazine, combined with his 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and his extraordinary account of the following year’s US election, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, meant that, by the time of the Rumble in The Jungle, fought in Zaire in 1974, Thompson was one of the most in-demand, highly-paid and celebrated journalists America had ever produced.

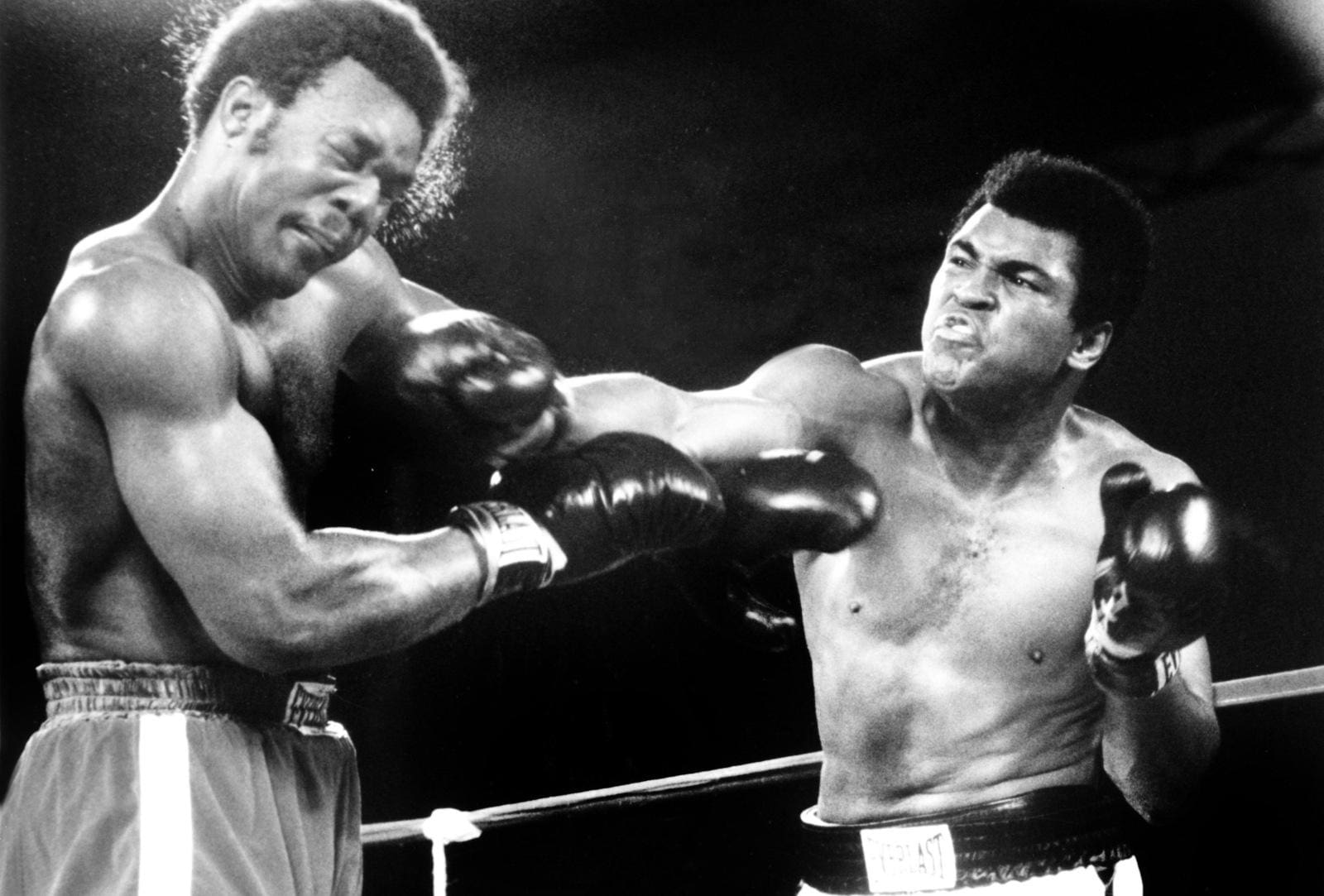

The fight itself, between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, was a global event, orchestrated by Zairean President Mobutu as a showcase for African power and liberation from the colonial yoke.

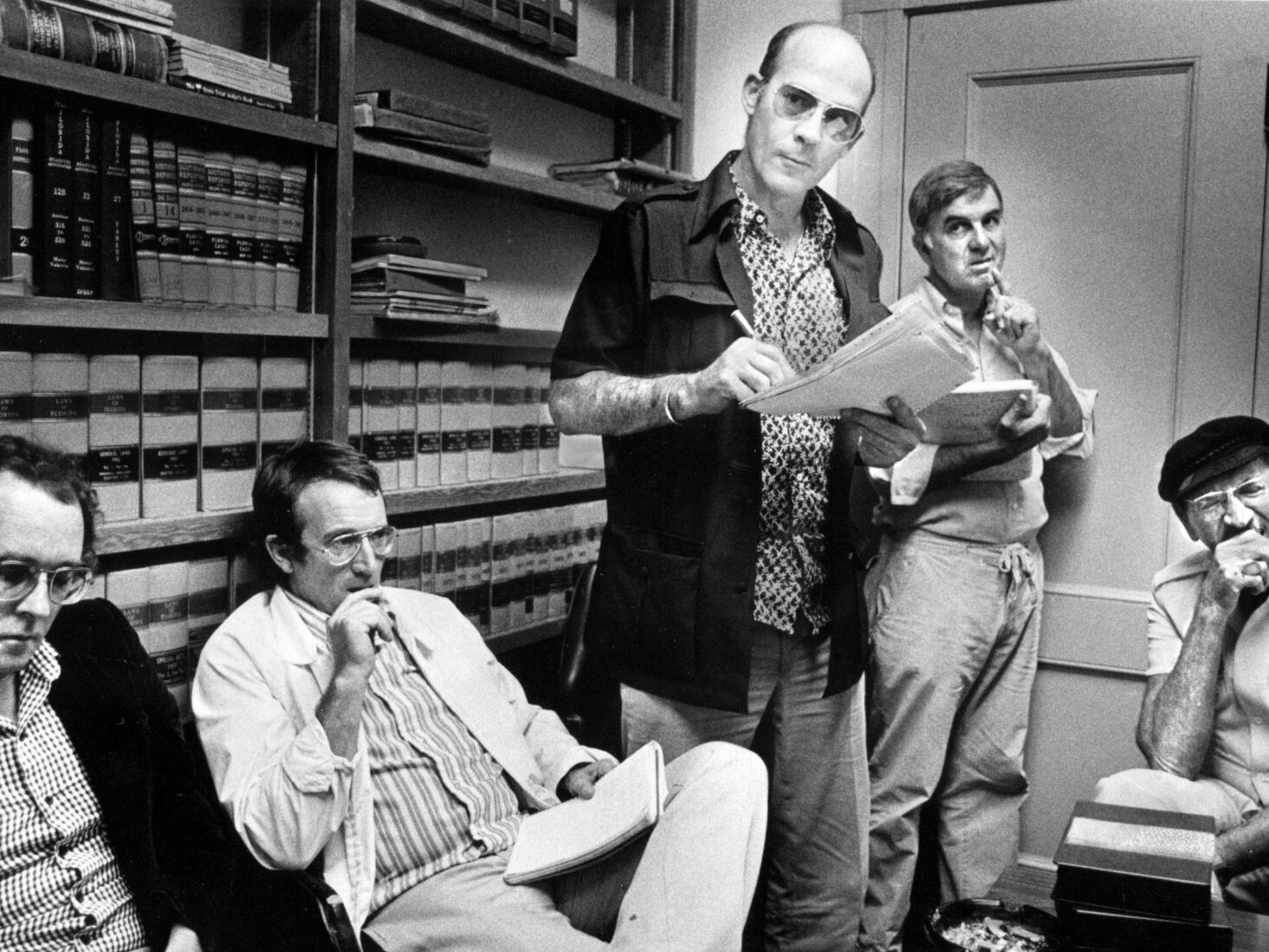

The entire world wanted to watch the fight. And Hunter had a front-row seat alongside other writers such as Norman Mailer and George Plimpton and a bewildering array of celebrities flown in from the States to perform before the bout, including James Brown, Bill Withers and BB King.

For Thompson, deployed to cover the fight for Rolling Stone, everything seemed in place for this to become one of his most celebrated pieces of writing; the enfant-terrible of American counter-culture, travelling to the heart of Africa to watch a fight taking place in the middle of a nation living under a violent and corrupt dictatorship where any dissent was brutally repressed.

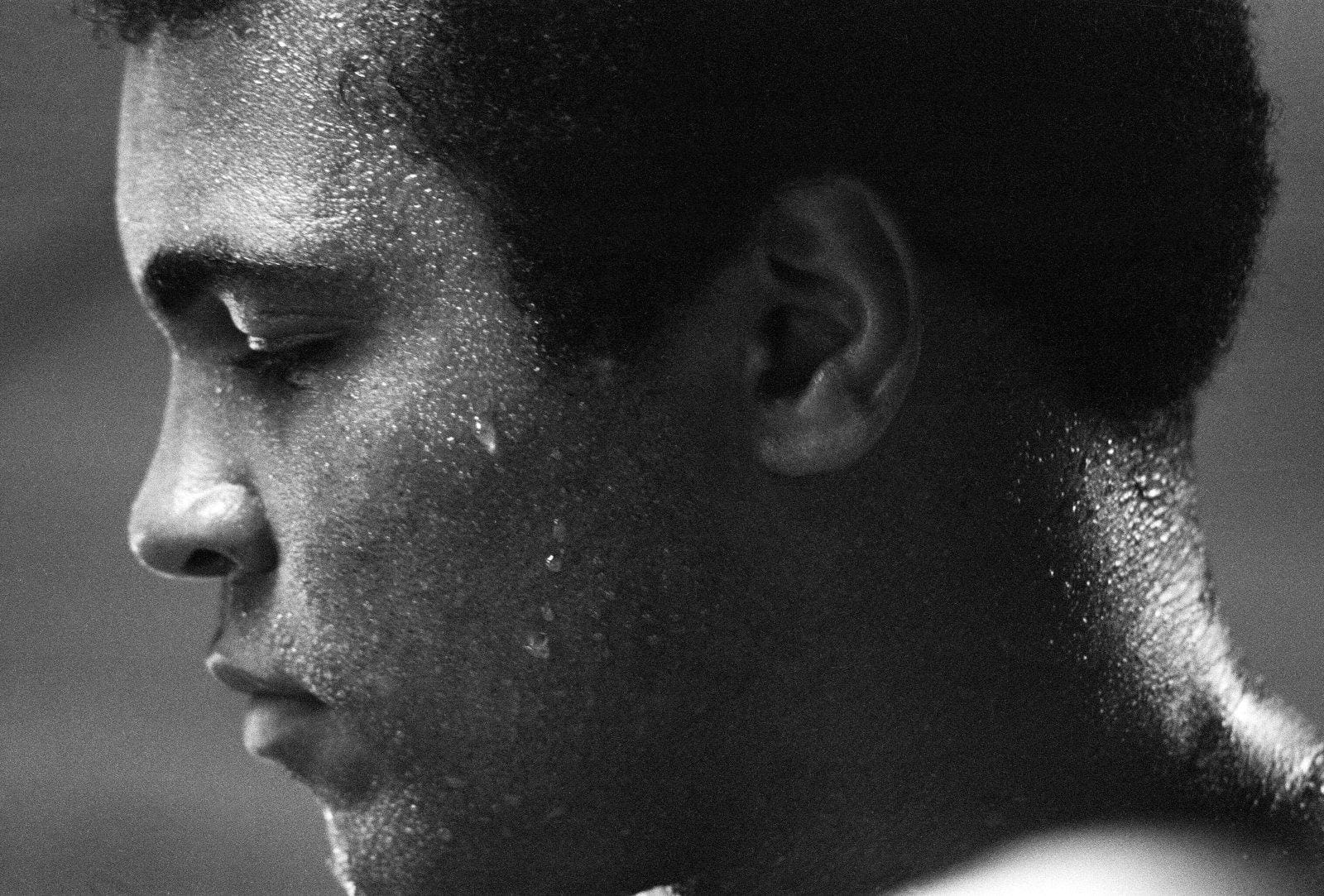

Thompson had previously gone on record as being a fan of Ali. Writing in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas under his alter-ego Raoul Duke, he ruminated on Ali’s loss to Joe Frazier in 1971, noting that Muhammad’s victorious opponent ‘had finally prevailed for reasons that people like me refused to understand – at least not out loud.’

But, three years later, by the time of the fight, any passion for the sport of boxing seemed to have collapsed for Hunter. According to Ralph Steadman, Thompson’s close friend, illustrator, and a man who joined him on the trip to Zaire, “all he wanted to do was swim or sleep or take drugs.”

“If you think I’m gonna watch a couple guys beat the shit out of each other,” Steadman recalls Thompson saying, “you got another thing coming.”

This contrarian approach to public events worked wonders for Thompson in the past and resulted in the cynical yet compelling masterpiece of his Campaign Trail ’72 book. But this time around, his trademark nonchalance and disdain wasn’t journalistic bromide designed to put his fellow sportswriters off the scent. It was a genuine disregard for doing any work at all.

Back in the Rolling Stone offices in San Francisco, editor Jann Wenner was beginning to worry about what he would receive in return for the vast amounts of money that Hunter had demanded as a fee on top of the expenses of flying him and Steadman to Africa and putting them up in Kinshasa’s Intercontinental hotel.

“He was letting his energies and his talent dissipate,” Wenner recalled. “He should have written an 8,000- or 10,000-word description of it and been done with it… It was one of the best sports stories of the decade and Muhammad Ali was one of his idols. He was from Louisville and Hunter always said he was some sort of distant relative.”

Thompson, after all this, did in fact have a plan on how to get the ultimate scoop over all his journalist rivals. His mission was not to watch the fight from the press box but at the side of President Mobutu Sese Seko himself, either at the stadium or in the Presidential Palace.

“He figured he was going to ace the whole goddamn thing,” recalled Norman Mailer, whose own account of the Rumble in The Jungle, The Fight published in 1975, is now considered one of the greatest, if racially contentious, pieces of sports writing of all time. “He had a basic knowledge that he wasn’t going to learn more about prize fights in a week or two than the rest of us had already known for years, and so he had to make an end run around us.”

Thompson tried to ingratiate himself with the presidential entourage but failed. In a fit of pique, on the evening of the fight itself, he sold his press tickets and retreated to the hotel swimming pool.

“I’m not going now. I don’t want to see the fucking fight,” are the words Steadman recalls Thompson hollering at him. “You can go somehow Ralph. I don’t know how, but watch it on television or something. I’m doing something else. I’m trying to find out where the money came from to put this fight on. But the fight itself. That’s not important.”

And so, as Ali staged one of the most astonishing boxing comebacks ever seen to beat Foreman in front of a televised audience of one billion, Ralph Steadman was stuck in a hotel room just a couple of miles from the stadium while Hunter floated in the pool outside.

“I lay on my back looking at the moon coming up and the only person in the hotel came and stared at me a long time before he went away. Maybe he thought I was a corpse,” Thompson told boxing writer George Plimpton, who came to the hotel to find him the next day.

“I floated there naked,” he told Plimpton. “I’d thrown a pound-and-a-half of marijuana into the pool – it was what I had left and I am not trying to smuggle it out of this country – and it stuck together there in a sort of clot, and then it began to spread out in a green slick. It was very luxurious floating naked in that stuff, though it’s not the best way to obtain a high… I went to bed after my swim, so I got the news this morning. Somebody slipped the hotel newspaper under the door.”

It was an 8,000 mile trip for Thompson to travel from his home in Colorado to the Zairean capital. A long way to travel for a stoned, late-night swim in a hotel pool. Before leaving the country, Thompson decided to create even more trouble for himself by buying two illegal elephant tusks in the Kinshasa ivory market. Reaching almost to the ceiling in his hotel room, Thompson later claimed he had been stopped by a gun-carrying member of the military as he was driving 100mph around a city roundabout.

Clambering into the vehicle, the soldier had attempted to force Thompson to drive straight to the city jail with his tusks. Claiming not to understand the man’s demands, Thompson floored the car straight back to the Intercontinental hotel, fleeing into the lobby with his illegal haul while the soldier impounded the car.

Wearing aviator sunglasses and refusing to leave his hotel room, Thompson ranted to George Plimpton who was, by this stage, understandably wary of the mental state of his Rolling Stone counterpart: “This is a bad town for the drug scene. In Nevada you can shoot anything into your body you want. You can get stark naked and lie in the backseat of a Pontiac with the accelerator wired down, and touch the steering wheel from time to time with a toe, and if you lose control at 120mph going along Route 99, all that happens is that you spin out into the desert and kill a lizard. But Kinshasa… it’s a bad scene.”

Observed drinking heavily and being in high spirits on the long flight home, Thompson retreated back to his self-proclaimed ‘bunker’ in Woody Creek, Colorado, intact but without a single word of copy to file to his editor.

The failure, considered to be the most expensive magazine story never published, marked a turning point. Thompson would recover from the Rumble in The Jungle debacle, but this fiasco marks the moment when his career began its slow, downward trajectory.

Thompson would never write another truly great book after Kinshasa and, as the 1970s limped to a close, his journalism increasingly seemed to be little more than faint impersonations of his earlier reporting. Travelling to Saigon in the dying days of the Vietnam War again for Rolling Stone (which, incredibly, continued to commission him even after the Zaire fiasco), Thompson spent most of his time in a hotel courtyard chatting to other hacks.

When he finally did meet Muhammad Ali, in a New York hotel room in 1978, the resulting story, Last Tango in Vegas: Fear and Loathing in the Near Room, was a colossal disappointment; a rambling piece of prose devoid of questions, where Thompson and Ali merely quip unconvincingly about drunkards and unsweetened grapefruit.

Thompson’s ego, more rampant and obnoxious than it had been during the peak of his writing, dominated his encounter with Ali, not a man lacking in ego himself. “I was, after all, the undisputed heavyweight Gonzo champion of the world,” wrote Thompson, “… and this giggling yoyo in the bed across from me was no longer the champion of anything.” It was an occasion when Thompson, just once, should have jettisoned his desire to put himself at the very centre of every story he wrote.

Thompson would outlive the country of Zaire. The reign of Mobutu collapsed in 1997 when a rebellion by the ethnic Tutsi population forced him into exile. He fled to Togo and then Morocco, where he died later the same year aged just 66. Zaire was swiftly renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo but is no less chaotic, dangerous and corrupt today than it was in Mobutu’s time. The Stade du 20 Mai stadium still stands – although it’s now called the Stade Tata Raphaël.

Thompson, in a wheelchair due to chronic back pain, his body wrecked by decades of monumental drink and drug consumption, took his own life in early 2005. Ali would suffer even worse physical deterioration. He continued, unwisely, to prolong his competitive fighting career until 1981, when the first effects of Parkinson’s disease were clearly apparent. It would ravage his body and mind in his latter decades until his death in 2016.

Almost half a century on from the Rumble in The Jungle, and with few remaining first-hand witnesses to the event, there is a sizable Thompson-shaped hole in the reportage that emerged from the remarkable fight in a country that no longer exists.

As Wenner, the editor of Rolling Stone who was left without a single word of copy to publish, later admitted: “He was high functioning for a long while and he had his brilliant period. But then he kind of let his talent slip… Editing Hunter required stamina. It was a bit like being a cornerman for Ali himself…”

Read more: Get Back – The inside story of the Beatles’ final album