Christine Keeler and the chair that ignited a revolution

In 1963, an image of Christine Keeler straddling a plywood chair captured the world. 60 years on, the ‘Keeler chair’ has outlived its namesake

Soho, 1963. It’s mid-morning in May and as a young woman ascends the rickety steps at the back of a nightclub, the wooden treads under her high heels creak in a manner that sounds, appropriately enough, vaguely indecent. In the name of publicity, those heels will shortly be removed, as will all other items of clothing worn by Christine Keeler that day.

19-year-old Keeler is a woman at the fulcrum of an inferno that is currently eclipsing the Cold War to make it onto the front pages of newspapers around the world. Her brief affair with Britain’s Secretary of State for War, John Profumo, and his subsequent denial of it to the House of Commons, has prompted a genuinely seismic scandal. It’s a tempest of such magnitude that it will shortly bring down the Conservative government of Harold MacMillan amid cries of moral iniquity from a public who, simultaneously, couldn’t get enough of this dazzlingly pretty young girl from Berkshire who, as would later emerge, was also sleeping with a secret agent from the KGB.

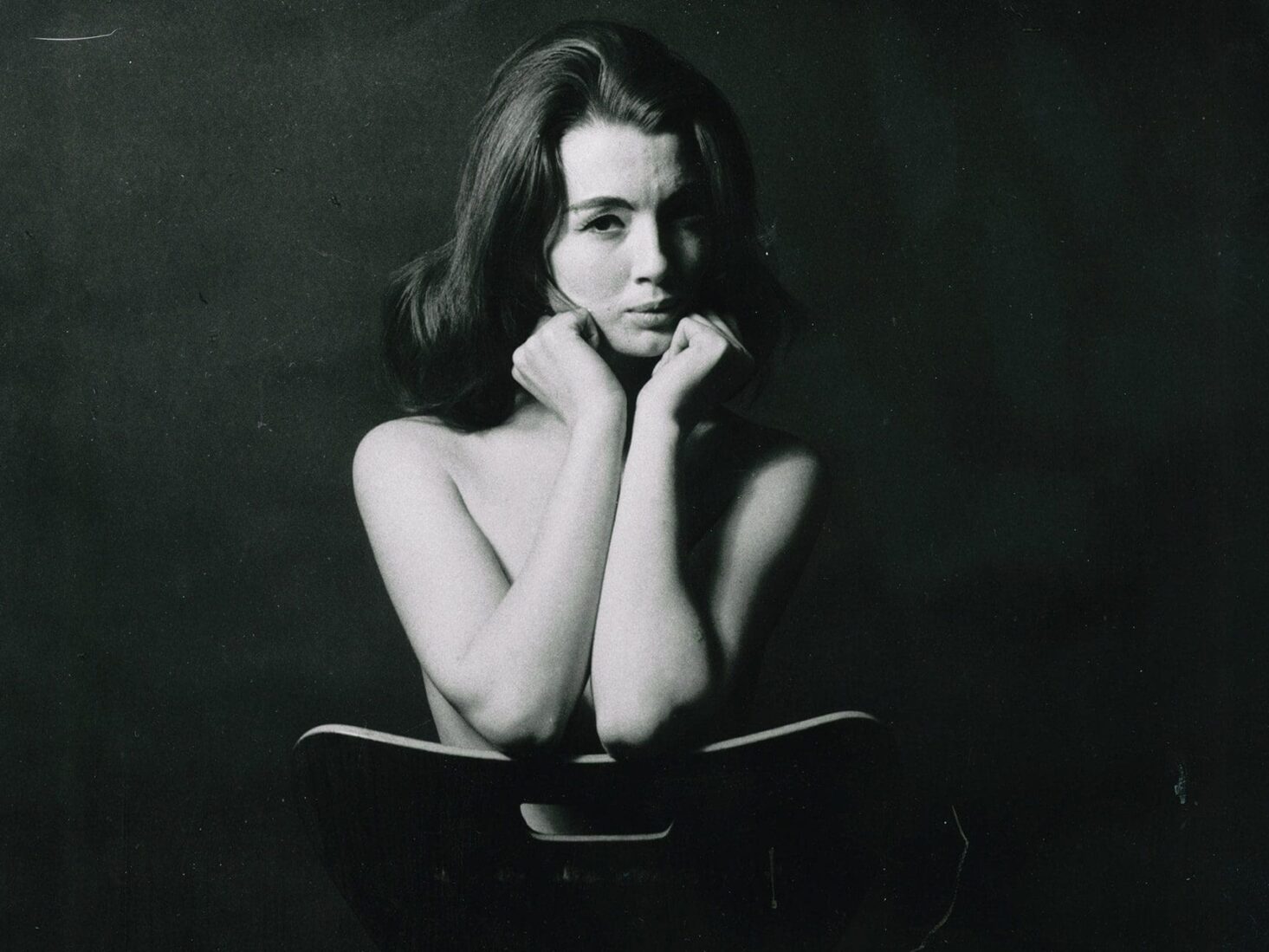

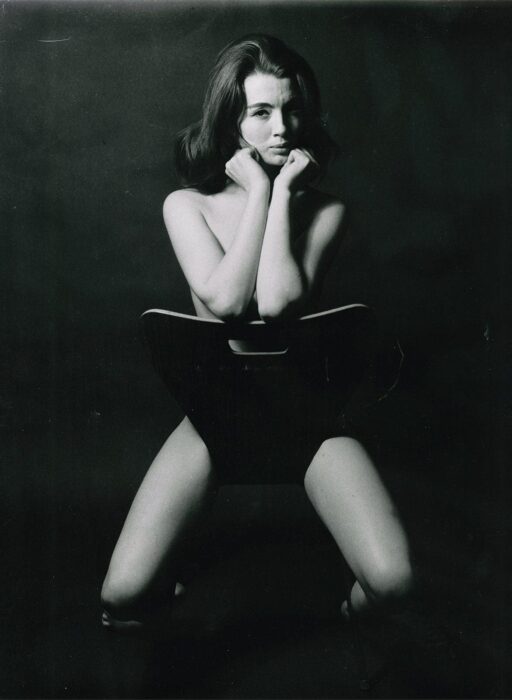

60 years on from what became known as the Profumo Affair, the most famous image pertaining to the incident isn’t of a cringing politician being rough-handled out of Parliament, or a baying mob of moral revisionists outside the Old Bailey. It’s of a chair, turned back to front, with a solemn-looking Christine Keeler sitting upon it, wearing nothing but a slightly contemptuous look intended to demonstrate just how au fait – and bored – she already is with the sexual revolution for which she has unwittingly become a totem.

‘At times over the years I have hated it,’ Keeler wrote of the image, years later. ‘It is always around and a constant reminder of those difficult days, but I do like it. I am now dealing fully with those times for I am no longer afraid of the fear.’

‘The Chair’, Christine Keeler by Lewis Morley, 1963. With special thanks to Keeler’s son, Seymour Platt

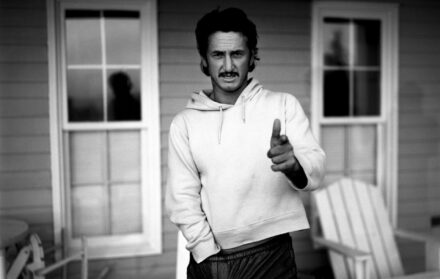

British Minister of War, John Profumo, returns home after admitting an affair with Keeler, June 1963

The photo was taken in a small studio on Greek Street, located above the Establishment Club, a short-lived but wildly successful cabaret and nightclub co-founded by the comedian Peter Cook. For a brief period in the early 1960s, the club would act as a centre for the ‘satire boom’ that launched Private Eye magazine and, possibly less thankfully to many, instigated the careers of future mainstream media stalwarts like David Frost and Barry Humphries, aka Dame Edna Everage.

The photo was the last shot on a 12-exposure film, taken by photographer Lewis Morley during a session that lasted less than five minutes. It was meant to provide a publicity still for a proposed film about the scandal, The Keeler Affair – a film that was never made. This wasn’t Keeler’s first visit to the nightclub studio. ‘When I explained to Lewis that the studio he’d hired was the studio that I’d had my portfolio taken in, and that I had already used all the props, he was a little taken aback,’ Keeler wrote in her memoir, Secrets and Lies.

‘But then looking around he [Lewis] grabbed the chair. Edgar Brind [the owner of the Greek Street studio] had sat on it to take my earlier photographs. Lewis insisted on using that chair in every shot, which I found not particularly creative and quite boring – of course, it was anything but boring in the years that followed.’

The chair is an imitation of a design created by the Danish artist Arne Jacobsen, a former apprentice bricklayer who, to avoid deportation to a Nazi concentration camp, fled to Sweden during the Second World War. Jacobsen would later be held up as the ‘father of Danish modernism’; his ‘egg’, ‘swan’ and ‘ant’ chairs considered classic contributions to the canon of post-war domestic design.

Keeler’s chair was a cheap riff of Jacobsen’s ‘Model 3107’, Morley having bought half-a-dozen imitations from Heal’s department store in London for five shillings apiece in 1962. With its pulchritudinous curves and cinched waist, the chair made a perfect silhouette to Keeler’s naked form. Morley’s shot captured one of the most tinnitus-inducing explosions in post-war British society; turning the hard edges and unforgiving heft of Edwardian morality and its concomitant architecture into kindling.

Although the illusion was that I was totally naked, I wasn’t… Most importantly, I did not smile, believing that sex was a serious matter

Christine Keeler

This was the moment where the last, grimy sheaves of pre-war rectitude disintegrated, to reveal a new decade where the things we looked at – from chairs, to the models sitting upon them – were no longer lathered in false layers of flyblown decorum and prudishness. Chairs could be sexy. Christine Keeler was sexy. And despite the rabble-rousing from the Church of England and broadsheet newspapers, nobody could tear their eyes away. Sex, and designer furniture, it seemed, were getting as easy to acquire as a matchbox to burn your flat cap or demob suit.

Despite being under contract with the News of the World to reveal her story exclusively on successive Sunday instalments, it was the rival Sunday Mirror who first published the ‘Keeler chair’ picture, with the negatives having been ‘stolen’ from Morley’s studio. How exactly that happened remains unknown.

Keeler en route to see Lord Denning in connection with his inquiry into security aspects of the Profumo affair, July 1963

Christine Keeler, right, with two friends, leaving Marylebone Magistrates’ Court, October 1963

When the media attention finally died down, Keeler returned to relative obscurity, working as a dry cleaner and a dinner lady before her death, aged 75, in 2017. It was, arguably, Morley’s chair – the collections of furniture designers the world over still containing ‘Keeler chairs’ today – that would live longer in the public consciousness.

Having disappeared into the attic of his sister, who had almost donated it to a car boot sale, Morley’s chair was only retrieved when the poster for the 1989 film Scandal, starring Ian McKellen as John Profumo and Joanne Whalley as Keeler, revived interest in the famed chair in which the teenager had sat. Now on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum – along with Jacobsen’s original Model 3107 – the underside of the chair is signed by Morley and inscribed with the names of Humphries and Frost who, in the spirit of satire, couldn’t resist having their own nude ‘Keeler shot’.

Yet, to the disappointment of the more lascivious members of the public who devoured Morley’s pictures, Keeler spent much of the rest of her life having to insist that she was never actually naked at any point during the shoot. ‘I am always asked if I wore knickers for the shot astride the chair,’ she wrote. ‘I certainly did, but it had been a battle to keep them on. Morley had wanted to photograph me without any clothes on but I used the chair to cover my bust and pulled up my white knickers around my waist. Although the illusion was that I was totally naked, I wasn’t… Most importantly, I did not smile, believing that sex was a serious matter.’

Serious it may have been for Keeler, and certainly also for the Conservative party at the time. But Keeler’s more than slightly uncomfortable photoshoot, as exploitative as it may seem now, set free a generation of post-war youngsters who, for the first time, could see sex as something infinitely less laden with morality and fear. Sex, in the decades after Keeler’s photoshoot, would become as humdrum and unremarkable as the cheap plywood on which she sat during that May morning in Soho.

Morley’s ‘Keeler chair’ and Arne Jacobsen’s original ‘Model 3107’ now belong to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Furniture and Woodwork Collection, visit vam.ac.uk

Read more: The 50-year tangle of Marlon Brando’s ‘Last Tango in Paris’