What is real tennis and where can I play it in London?

Rob Fahey, aka the Roger Federer of real tennis, helps explain why the waiting list for membership at the sport’s London-based clubs is at an all-time high

Imagine watching a game of tennis, just as many at Wimbledon would have been hoping to do this week. The ball goes back and forth, back and forth and, as long as it goes over the net, and stays within the court as mapped onto the ground, the match goes on. Now, imagine the same game, but with walls you can play off, one even with an odd protruding buttress, with galleries you can play into and even sloping roofs you can knock the ball onto as well.

“It’s not just a matter of getting the ball back over the net,” says Robert Fahey. “It really has to be the right shot at the right time. Of course, I’m sure Federer and Nadal would say the same thing. But they don’t have to play off corners. They don’t have to read the spin of the ball off walls.”

Fahey knows of which he speaks. The Australian is the World Champion of what is known as real tennis – the sport that eventually gave us the better known lawn variety that we all watch around this time of year. Indeed, he is the superstar of real tennis, having held the title every year from 1994 to 2016, then recovering the title in 2018 and retaining it until today.

Not that real tennis pays as well. Last year saw the WTA Finals in Shenzhen break the record for prize money – offering a potential $4.75m (£3.7m) to the singles winner alone. The British Real Tennis Open, by contrast, has a total prize purse of just £25,000.

Real tennis hasn’t attracted broadcast TV as of yet, which is a travesty, given that the likes of darts and crown green bowling have. But some of the bigger games of real tennis are live-streamed – and the sport is as fiendishly addictive to watch as it is hard to play. Just try YouTube. Think of real tennis as tennis crossed with squash, chess and American football, played with a ball – hand-made from cork, upholstery tape, string and felt – that’s hard and very fast. Oh, and it’s played on courts that can vary in size, degrees, surfaces and materials, too.

“Real tennis is just so much more satisfying, especially to play. It’s the sheer pace of it, relative to lawn tennis – and there’s so much more to learn,” says Fahey, who was a state lawn tennis champion in his native Tazmania before discovering the real thing. “I’d never heard of it when I started working at this local real tennis club. But I thought it was incredible – completely nuts but incredible. You learn to read the travel of the ball to within two to three centimetres every time, and give yourself only two to three metres to get to it. Fitness is important of course, but it’s more of a mental game.”

Fahey is 52 – and still winning. His one championship loss was to a 28-year-old American player with the unlikely name of Camden Riviere – it’s the fist-pumping, teeth-clenching Riviere, now 32, who met the more low-key and laid-back Fahey in April, and this time lost.

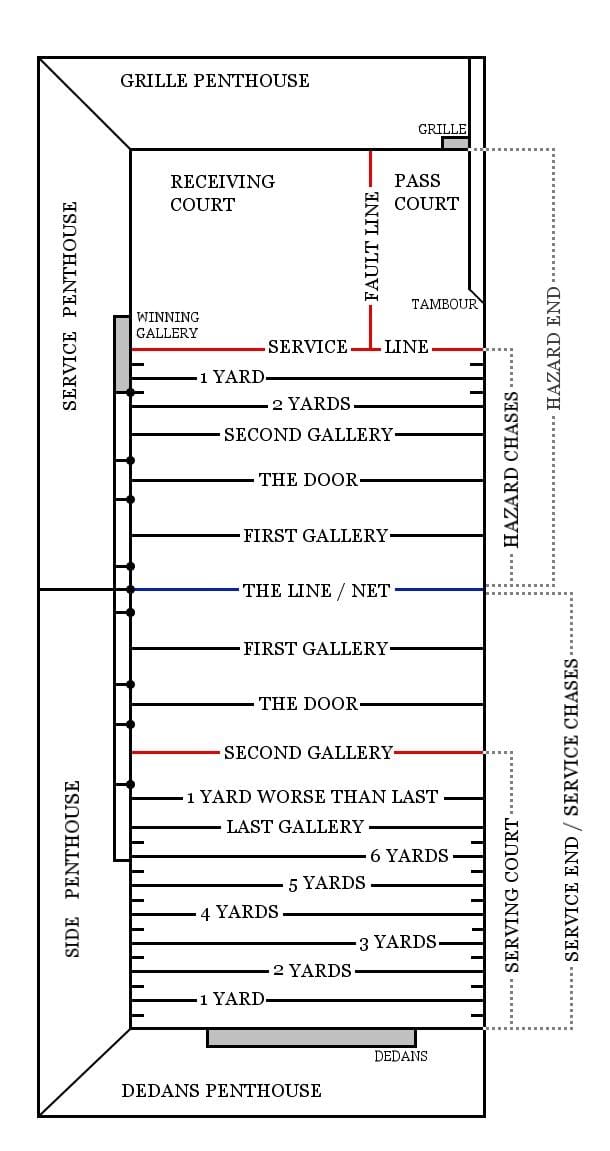

There unseasoned spectators may find the language romantic but puzzling: the sloping roofs are called ‘penthouses’; the non-serving end – for service is only from one end in real tennis – is the ‘hazard’; an opening at the rear of the court, which can be played into like a goal, the ‘dedans’. There are various kinds of service – the bobble, pique, giraffe and poop among them – and the court is marked out in stages known by names the likes of ‘the door’, the ‘last gallery’ and, best of all, ‘one yard worse than last’.

They may also find the rules unfeasibly complicated, not least what’s called ‘laying a chase’ – because the ball is so hard and fast, players aren’t really expected to return every shot on the first bounce; so at some stage in the game the recipient of the shot will be given another chance to win the point by playing within the space prescribed by where the previous shot landed. Or something like that.

The layout of a real tennis court. A valid serve must occur from the serving court before the second gallery line, and hit the service penthouse before dropping in the receiving court, marked by the service line and fault line.

“It’s not really as complicated as people think if they haven’t had it explained on a court,” Fahey laughs. “It can seem like there are five million rules and during play it can feel like there is a lot going on. It’s certainly not as simple as a lot of racquet sports. That’s why most spectators – and typically there’s not much room for many of those – tend to be players too. But what seem like complications to the uninitiated are actually what make the whole game work. Without the rues it would be a stupid game – you’d just belt the ball at 500mph right by your opponent. With them it has all these added dimensions. It’s unbelievably clever.”

Real tennis is also unbelievably old. Deriving from a version of handball, real tennis dates at least to the 16th century, with its home in France; in 1596 there were said to be 250 courts in Pairs alone.

There’s also good reason why it’s been dubbed ‘the sport of kings’ – in France, Francois I and Henry II both played, while Charles VIII died from a bump to the head sustained walking onto a court. In England, Henry V was a keen player, as was Henry VIII. That’s why there’s a real tennis court at Hampton Court Palace. It’s said that Anne Boleyn was watching real tennis when she was arrested; and that Henry was playing it when she was executed. Queen Victoria didn’t play but Kensington’s Queen’s Club, to which she lent her name, does have two real tennis courts. There are courts, too, at Lord’s and at Newmarket.

Elsewhere, however, courts are few and far between these days. There are courts in Australia, Ireland and the US, but only an estimated 43 courts remain, world-wide, even if over half of these are in the UK – 26 courts for some 5,000 players. The last couple of decades have seen some 20 new courts built around the world – including ones near Oxford and Reading. With Britain failing to regularly produce lawn tennis stars – in part, it’s said, because of the lack of public facilities, meaning paying for club membership becomes necessary – real tennis is esoteric on another level.

“We certainly can’t afford to take the foot off the pedal [in ensuring its survival],” says Fahey, who has an MBE and last year was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to real tennis. “It’s easy to say that it’s in good health but lose a couple of clubs, lose a sponsor, and it would be in trouble. The lack of courts certainly is an issue – there definitely isn’t the court time to let everyone play who wants to. And they’re not easy to build either – they have to be very sturdy. They’re kind of like bomb shelters.

“But that’s not the biggest problem,” Fahey adds. “Real tennis is also difficult to film, because no one camera position can capture the whole event. It doesn’t have one huge benefactor, which we’re always working on but which I wouldn’t bet the house on the sport finding. Then there’s the misapprehension that the sport is in some way elitist and that plays against people giving it a try. People who play racquet sports think that they’re not posh enough to play.”

Fahey says April’s World Championships were his last: “it takes a lot of time to be good at something like this, but I’ve had enough – it’s time to retire.” He says he’ll spends as much time behind the scenes trying to pump new life into the sport. He heads up a juniors’ training programme and is involved with a charity that has introduced real tennis to some 500 school children over recent years. Then there are attempts to design some kind of flat-packed, pop-up real tennis court – not as good as a purpose-built court perhaps, but one offering a sufficient standard of play to allow the introduction of the sport to many more people.

“It would be great to put a temporary real tennis court up for six months, alongside a tennis court, or at a school, for example,” says Fahey, “but as with all these ideas it comes down to resources. That said, the number of people playing real tennis is [relatively speaking] so small that there’s almost a collective feeling to it all. Everyone who plays it is in some way involved in keeping it alive. And, you know, real tennis has been going for several hundred years and it’s still here – so it must be doing something right.”