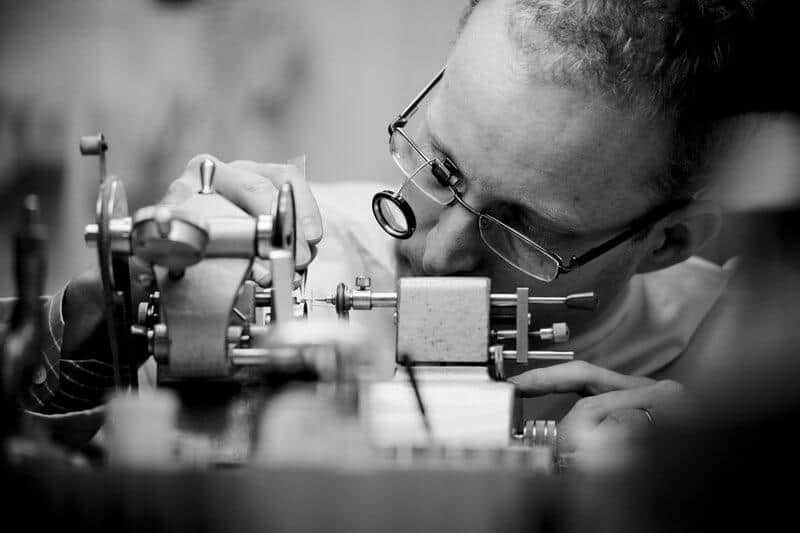

Roger Smith: The Timely Englishman

One of the few people to have mastered the 32 skills necessary to design and create a mechanical watch from start to finish, Roger W. Smith has earned his place among the world’s best watchmakers –

It’s an awkward question, being asked what it feels like to be cited as the world’s best watchmaker. “I can feel myself turning red at the idea,” says Roger W. Smith. “It’s not a label I really think about – I just get up each day and try to make watches you can’t find anywhere else. I’m actually at the work bench 95 per cent of the time. Being a watchmaker is all I’ve ever done since I was 18 and that’s where I’m happiest. It’s where I can command my own little world.”

Smith’s customers aren’t what he calls “fast money clients”. With his timepieces commanding six-figure sums and a probable wait of several years, his clientele are fascinated with watchmaking, and revel in the processes and in mechanisation. Smith was appointed an OBE in 2018 for services to watchmaking and jokingly claims that he “still can’t get a table at a restaurant”. He currently makes around 10 watches a year, though he plans to increase production numbers to the heady heights of 13. “I’m certainly proud to be one of the smallest makers in the world,” he laughs. “Companies tend to announce their annual increase in production as though it was a recognition of doing well, but if I made 20 watches a year I’d know something must have gone down in quality.”

What is even more incredible is that Smith makes every single part of every single watch, having also mastered each of elite horology’s specialist decorative skills. Not a screw is imported, not a part farmed out, and this approach is unusual enough even among watch brand giants. This perhaps explains the prices – typically on application but, to give some context, when two early R.W. Smith watches came up for sale online in 2016, an almost unheard of event, they were priced at £150,000 and £235,000 respectively. It’s certainly impressive for someone who once worked part-time doing repairs for mass-market British jewellery brand H. Samuel.

Smith did, he admits, have something of a useful education. He says he “could never see the point” of school and it was his father, an antiques collector, who suggested he look into watchmaking. Aiming high – very high – Smith decided he would make a pocket watch for the late George Daniels, often proclaimed as the greatest watchmaker of the 20th century and the inventor of the hallowed co-axial escapement.

Some 18 months of midnight toil followed. Smith approached the god-like Daniels with his offering. The watchmaking supremo told him it was not a bad effort – or words to that effect – and to try again. Undaunted, Smith did just that and at the age of 19 found himself at Daniels’ workshop on the Isle of Man. He was the master’s one and only apprentice, the Luke Skywalker to Daniels’ Obi-Wan Kenobi. Smith still lives there today and has recently built a new workshop space in a converted agricultural unit. “I’ve got a bit of a commute now, about 200 yards,” he laughs. He’s taken on four of his own apprentices, each of whom have likewise moved.

This remote spot meant Smith’s training was unpolluted by the received wisdom of Swiss watchmaking’s approach to case or movement making. Every solution he created was an original one and, in time, Smith would produce historic masterworks, including an improvement to Daniels’ own escapement. This involved radically lightening it and in turn increasing the service interval for a mechanical watch to more than 10 years, way ahead of the industry standard. He also developed a style of his own, characterised by a raised barrel bridge, jewels in gold chatons, silver dials and gold hands. Smith has just put the finishing touches to the design of his new Series 4 watch, which features what he believes is a watchmaking first. The instantaneous triple-calendar piece has a date indicator that travels around the outer edge of the dial, negating the need for a date-hand that often obstructs details on the face.

“As I get older I realise that my level of interest in watchmaking when I was younger was unusual, but it’s always been normal to me,” says Smith, whose spare time, unsurprisingly, likewise leans towards all things mechanical, be that gauge one model railways or doing up his 1967 Mini Cooper. “My first memory was sitting in a high chair eating a rusk or something – when I was two maybe. I can still picture the 70s kitchen very vividly. I suppose I should say that I then looked up at the kitchen clock and the rest was history, but that didn’t happen.

“As a small boy I did have this obsessive quest to make things perfect. My first model aircraft had glue everywhere, so I kept going until there was no glue visible,” he adds. “I think I found the right outlet in watchmaking. I’d probably be too nervous to approach George for the first time now if he was still around, but then I wanted to prove – to myself and to him – that I could do it. At that age I didn’t know what else to do. I’d always been impressed by George. He was very charismatic and doing something nobody else in the world was doing.”

When Daniels died, he bequeathed all of his watchmaking tools to Smith. “And I can pick up those tools and still think what great watches were made with them,” he says. “They’re a reminder not to stray. Like George, I want to make watches that fit into the great watchmaking tradition. No, my watches won’t keep better time, and it’s true that a cog handmade is probably no better than one stamped out by a machine. But not using anything other than very traditional techniques means those watches will be around for centuries. And I wouldn’t be happy with anything less.”

It would be easy to ascribe to Smith the stereotype often employed with Swiss watchmaking. Despite most of the production being high-tech and industrial, we still think of the slightly hunched, vitamin D-deficient figure in a leather apron beavering away silently in an Alpine chalet. Smith, of course, works at another, more rarefied level, but he’s also not averse to exploring new ideas. Earlier this year he launched a research project into the use of nano-materials with Dr Samuel Rowley-Neale and Dr Michael Down of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Manchester Metropolitan University. Mechanical watchmaking’s biggest problem is lubrication, as the many moving parts periodically have to be oiled. Giving these parts a permanent nano-coating could do away with that inconvenience and cost.

Roger W Smith Series 5 Movement

Roger W Smith Series 5 Movement

Roger W Smith Series 5 Open Dial

Roger W Smith Series 5 Open Dial

“We’re still at the testing stage but the fascinating thing is how counter such a development is to the received wisdom of watchmaking. And solving the lubrication problem would be a really serious advance in mechanical watchmaking,” he says. “I’m sceptical of a lot of materials now used in watchmaking – the likes of carbon fibre – because they strike me as trendy and because they won’t necessarily be around in, say, 100 years. I like the idea of the watches I make having that lifespan and much more, in the same way that you can take a pocket watch that’s 300 years old and, with minimal work, it will keep as good time now as it did when it was made. Carbon fibre looks good, but it doesn’t improve time-keeping. And that’s what I get off on, so to speak.”

Roger W Smith The Great Britain

Roger W Smith The Great Britain

Roger W Smith The Great Britain Case Back

Roger W Smith The Great Britain Case Back

Smith jokes that he’s one of those lucky people who can’t wait to get to the office each morning, and his raison d’être is to take a craft that’s been evolving for the best part of half a millennia and play his part in moving it a few notches forward. He concedes that, on one level, it’s a strange thing to do with a product that’s outmoded in the digital age. But, on another – regardless of one’s interest in watches – it’s about as perfect an expression of the poetic possibilities in the space between man and machine as one is likely to find in the 21st century.

“George would say you have to be your own best critic. You have to be ready to throw away something you’ve been putting effort into for days or weeks,” says Smith. “When I was starting out that would mean a constant inner battle to accept something wasn’t right. And I still throw away several components every month and start over again. But now at least I can see the issue coming and react faster, and so limit the damage. It doesn’t feel as galling as you might expect.”