Uptown trunk: How Vilebrequin revolutionised men’s swimwear

50 years ago, a French motoring journalist doodled a sketch on a café tablecloth that would change what men wore to the beach forever

St. Tropez. Summer 1971. The long, off-white tassels that hang from the fringes of the canary-yellow parasols ripple, coquettishly, in the breeze. Amid the tall glasses of pastis and ashtrays brimming with the butts of languorously-smoked Gitanes, lunchtime diners, in flowing, printed dresses and shirt lapels that seem to be getting wider by the hour, look out at the vanilla-soft sands of the beach in front.

Try as they may, they can’t avert their gaze from one man standing in the shallows, dressed in nothing more than a pair of thigh-high shorts, the pattern of which is a fiesta of thick vertical stripes in striking blue, yellow, green and purple, a pattern that seems to flicker in the early-afternoon sun.

Who is this man? Could it be Alain Delon, fresh from the bruising travails of his latest Parisian heist movie, Le Cercle Rouge? The only person in the café that knows for certain is the photographer and motorsports journalist, Fred Prysquel. The lone swimmer isn’t famous. He just looks famous. It’s the shorts, Prysquel likes to think, the pattern of which he sketched on a paper tablecloth in this very café the previous summer.

Vilebrequin is the French word for ‘crankshaft’, an oblique and recherché noun for a swimwear brand that, half a century on from its debut on the beaches of St. Tropez, continues to fuse a look that’s both exotically contemporary and ineffably routed in a long lost France of long Françoise Hardy hair, Serge Gainsbourg-smoked cigarettes and Ricard-soaked afternoons on the Côte d’Azur.

Colour blind from birth, for his first collection of swim shorts Prysquel used fabrics he’d brought back from African markets he’d visited the previous decade while completing military service on the continent. “In Dakar [Senegal], swim shorts were made of fabrics called ‘boubou’ or ‘wax’,” recalled Prysquel. “I loved them. When I left the army, I brought some home with me.”

Prysquel’s swimwear, or ‘bathing suits’ as he and the company’s successive owners preferred to call them, are garments that men from Nice to Newcastle should be thankful for in 2023 – even if they’ve never actually owned a pair. The cooler, looser shape of Prysquel’s tyro designs would, after all, be pivotal in achieving his grand ambition: to redefine the male swimming brief from an Antipodean attack on our eyes – and crotches –

to something far more fun, frivolous and flattering.

The previous decade, you see, had seen the ‘Speedo’ – a garment that remains a byword for every compelling argument for never visiting a beach – gain a global momentum beyond its native Australia. Prysquel’s napkin doodle reimagined the longer board shorts worn by surfers at the time, made them shorter, more fitted and more sartorial. His sketch became an antidote to the ‘budgie smuggler’ – that cheap, uncomfortable al fresco fashion statement that’s invariably worn by men whose physiques suggest a life of Big Macs rather than breaststroke. This was to be a Battle of the Bulge that had nothing to do with Panzer divisions in the Ardennes.

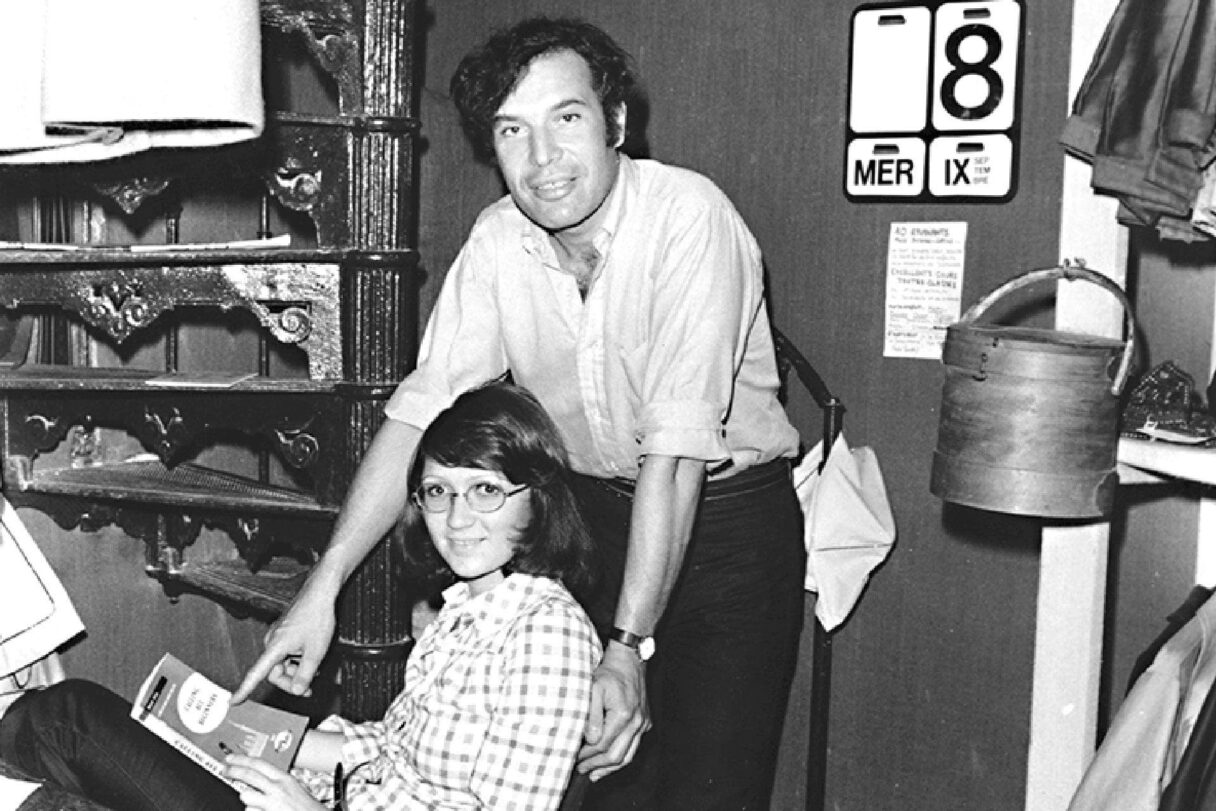

Persuading his wife, Yvette, herself a fashion designer, to stock his new designs in her St. Tropez boutique, Prysquel’s brazenly-colourful designs (Yvette would help pick the colours) had a strangely chimeric quality on their wearers that long-gone summer, his nascent brand quickly establishing a high-spirited and well-heeled audience in the south of France. Soon, the erstwhile motoring journalist was cajoling every female acquaintance in the possession of a sewing machine to turn their hands to making his dazzling bathing suits.

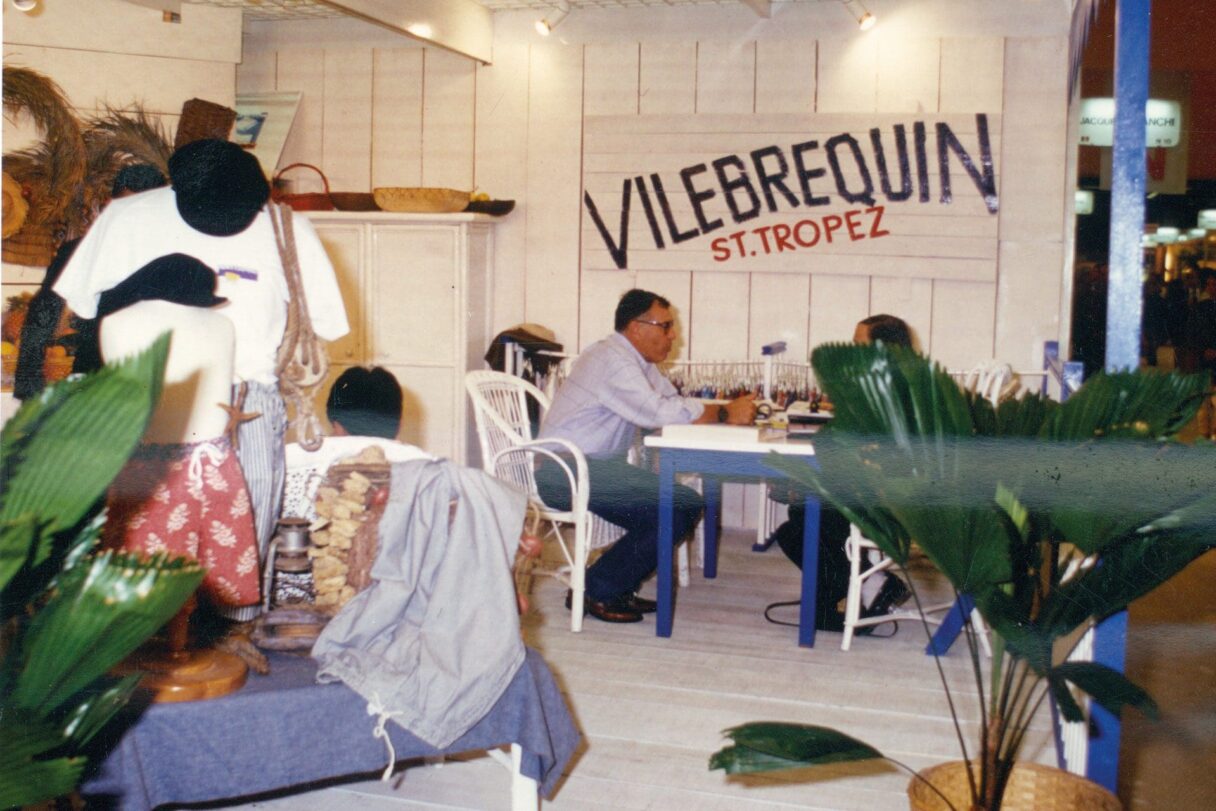

Prysquel would eventually sell Vilebrequin in 1991 to fellow Tropezian textile worker, Loïc Berthet. It was Berthet that added the now-signature Velcro back pocket and silver eyelet holes. He also introduced a cotton inner lining to the shorts. In 2012, the company was acquired by the G-III Apparel Group, the US clothing company that owns licenses to DKNY, Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger and Karl Lagerfeld. Yet the daring designs have continued; shorts with sea-turtle motifs, Portuguese azulejo tile mosaics, and crocodiles crawling through pink and yellow mangroves attracting new generations of men whose knowledge of Alain Delon is, you might assume, all but non-existent.

According to the experience of veteran, London-based personal stylist, Nick Hems, Vilebrequin seems to be more popular today than it’s ever been. “It’s amazing just how many of my female customers reach for a pair of Vilebrequin’s for their partners,” says Hems, “often without actually knowing the brand they’re choosing. They’re just the perfect ‘transition’ shorts, in the sense that you can wear them in pool bars and on café terraces and they’re not just for swimming or sunbathing. Plus, they’re form-fitting shorts – they really get the shape right.”

We may now look back at the smoke-fogged, sun-broiled days of 1970s St. Tropez through a sepia filter, but you can chalk Vilebrequin’s success to the fact it remains grounded in the legacy of that bohemian era. In 2015, the brand collaborated with the Rolling Stones on a range of shorts covered by a collage of some of the group’s most famous album sleeves (though, thankfully, the collection excluded the infamous ‘toilet bowl’ cover of 1968’s Beggars Banquet LP).

Vilebrequin x Deux Femmes capsule collection

Vilebrequin x Deux Femmes capsule collection

It was in the summer of 1971, the same year that Prysquel’s shorts debuted, that the tax-dodging Stones fled to Villefranche-sur-Mer, a small fishing village a few miles along the Côte d’Azur from St. Tropez. Holed up in a crumbling mansion that was once occupied by Nazi officers, the band festered in a makeshift studio located in the villa’s sweltering basement, recording some of the tracks that would appear on the following year’s Exile on Main St., their swampy, bluesy, nefarious masterpiece.

It was a collaboration that at first glance might not have screamed symbiosis. Yet, you might reasonably argue, what’s more rock ‘n’ roll than having a screwball idea and pursuing it full-leather? What’s more maverick than a motoring hack taking a punt on some retina-rattling swim shorts named after a crankshaft?

Modern as its swim shorts may look today, the triumph of Vilebrequin has everything to do with the gateway the brand unlocks to those dreamy, anything-could-happen '70s summers. Even now, Vilebrequin transports us to a simpler, more elegant time when men would hit the beach, in Prysquel’s words, with little more than “a comb, a lighter and a pack of Gauloises.”

Visit vilebrequin.com