Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto: Inside the V&A’s new blockbuster exhibition

A landmark retrospective at the V&A museum aims to explore how the designer’s six-decade career continues to influence the way women dress today

On 16 September 2023 Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto, the first-ever UK exhibition dedicated to the work of French couturière, Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel, launched at the V&A museum. Given that Chanel was one of the most influential designers of the 20th century, it’s surprising that there has never been a showcase of her work in the capital. Claims that she acted as a German spy during World War II might have something to do with that. In recent years, debates about how, and if, we should separate art from artist have only gotten fiercer. And while personal links uncovered by biographers between Chanel and certain German officers are hugely unsavoury, her professional legacy in the world of fashion, and the incontrovertible mark she left on women’s dressing, cannot be ignored – not least because it lives with us still.

When Chanel opened her first clothing boutique in Deauville, Normandy, in 1913 (a venture financed by an English suitor named Arthur ‘Boy’ Capel), Western fashion was still centred around the long, severe lines of the previous century. While corsets were on the decline, the hourglass shape still reigned supreme, as did stiff collars and broad hats. Women’s fashion was stuffy and uncomfortable during the Belle Époque (Beautiful Period) of the late 19th and early 20th centuries; Chanel set out to shift these parameters. “Nothing is more beautiful than freedom of the body,” she once said.

Chanel was one of the earliest champions of trousers for women, often borrowing pairs from her male lovers (she famously had a string of high-profile liaisons, including relationships with the Duke of Westminster and Prince of Wales, Edward VIII). Even before the style was popularised among women during World War I – women having taken on manual jobs previously done by men – the designer was sporting flowy ‘beach pyjamas’ while holidaying on the French Riviera (a bold statement at the time, given pyjamas’ association with the bedroom).

By the mid-1920s, wealthy women were eschewing the skirt, and Chanel is widely credited with carrying the trend from the realm of the practical to the fashion-forward.

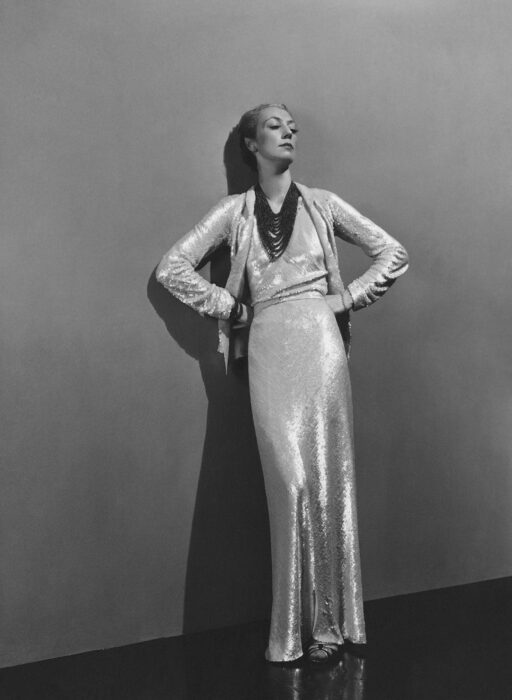

Roussy Sert wearing a long white sequin dress by Chanel, and a 15-strand coral necklace. Photograph by André Durst, published in Vogue December 15, 1936. Image: Andre Durst/Condé Nast/Shutterstock

Dorothy + Little Bara priest, Paris (Vogue), 1960. Image: William Klein

In 1926, Vogue published an image of a calf-length crêpe de Chine black dress, predicting that the piece would become the fashion equivalent of the Ford Model T: a versatile, accessible item with universal appeal. The ‘little black dress’, the publication claimed, was ‘a sort of uniform for all women of taste’ – and Chanel was its creator. Here was a dress that was simple, shapeless even, without a waistline or bustline in sight. The wearer could move freely, sit comfortably, and exist safe in the knowledge that their outfit was Vogue-certified.

The Chanel suit, similarly, was a game-changer for women’s dressing. The two-pieces, which were first introduced in the 1920s, were made using traditional tailoring methods previously reserved for men’s clothing, thus employing a functional cut that sat comfortably on the hips rather than cinching in at the waist. Chanel’s suits were made with tweed and jersey, fabrics that were considered distinctly un-glamorous at the time. Which, of course, was the whole point: the suit wasn’t meant to beguile suitors, but to be worn to jobs in business.

It wasn’t just garments; Chanel was also on a mission to revolutionise accessories. Take the Chanel 2.55, launched in February 1955 (hence the name). It was a luxury bag, ostensibly, but it came with a shoulder strap – breaking from the convention of clutches, which were the fashion at the time – which made it profoundly practical. The simple modification of a strap offered women a newfound freedom. Suddenly they could – wait for it – use both hands while out and about!

Then there was the Chanel sling-back, a shoe that mixed comfort and elegance with its black toe to protect from wear and tear, moderate heel height and asymmetrical strap, which kept the footwear in place. Even Chanel’s perfume range went some way to democratising fashion and beauty; when she launched Chanel No.5 in 1921 she reportedly charged perfumer Ernest Beaux with creating a scent that would make its wearer “smell like a woman, and not like a rose”.

There is a school of thought that says women’s clothing has played a key role in their subjugation over the centuries; that, drowning under heavy silks and marooned in vast bustles, women were kept symbolically ornamental, but also physically subdued. You try protesting for the vote while your breathing is being restricted by a corset.

I’m not saying that Chanel adhered to this notion, or was even cognisant of the concept (we must be mindful of conferring modern ideas on historical figures) but, retroactively, we can say with certainty that her designs contributed to the sartorial emancipation of women. Chanel not only freed ankles and loosened waistlines, but also updated the way that society viewed women: as people with agency, autonomy, and the right to move around in the world with the same freedom as men.

Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto is on until 25 February 2024, tickets £24, vam.ac.uk