Frank Costello: The fascinating story of the ‘real’ Godfather

When Francis Ford Coppola's masterpiece, The Godfather, made its cinematic debut half a century ago, there was one surviving mobster from the Mafia's golden age who in Marlon Brando's character may have spotted more than a

He survived an assassination attempt, valued brains over brawn, enjoyed a long marriage and adored gardening. As fanciful as these biographic details of the fictional Vito Corleone seem – this month marks half a century since the Mafia Don was first portrayed, unforgettably, by Marlon Brando in The Godfather – they are characteristics Mario Puzo’s character (Puzo wrote the book upon which Francis Ford Coppola’s film is based) shared with a real-life mobster, Frank Costello – aka the Prime Minister of the Underworld.

“I don’t think there will ever be another sitting boss who can meet with judges, political bosses and have that kind of unbridled influence… that’s something that happened under Frank Costello for just one era,” said John Miller Jnr, Costello’s godson, a former journalist who now, in a move unlikely to please his late godfather, is Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence and Counterterrorism at the New York Police Department.

The man who Mob historians and movie insiders believe was the basis for Don Corleone arrived in New York on a boat from Italy at the age of four. Born 26 January 1891 as Francesco Castiglia in Calabria, he quit school in the fifth grade and worked as a rent collector for a local mobster while his father ran an ailing grocery store. Determined to rise out of the poverty of East Harlem, Frankie, as he was now known, spent a year in prison in 1918 for weapons possession. Never again would he allow himself to be caught so easily by the authorities. Despite hailing from the south of mainland Italy at a time when leading Mob families, seeking loyalty and family connections, preferred to use only Sicilian immigrants, Costello worked his way through the ranks of American syndicated crime; preferring to use money, rather than threats, to ‘buy’ the people who mattered.

Costello even extended his formidable influence into New York politics. After amassing immense wealth and influence through bootlegging and bookmaking during Prohibition, Costello built a slot machine empire in New York and then New Orleans – the latter with the full support and endorsement of Louisiana governor Huey Long, just one of the many political titans who fell under Costello’s influence.

“The police were involved in Prohibition in the sense that they were moving liquor and smuggled booze for the gangsters, off-loading shipments,” says mafia historian, Anthony M. DeStefano. “The politicians saw the Mob as a source of cash, which politicians needed… The democratic machine… needed a good source of cash. The gangsters were that source of cash because they had a big stockpile of money from Prohibition. They were able to entice the politicians, who the mobsters needed to run favours.”

By buying off juries in his sporadic court appearances, Costello avoided another jail term and by his mid-30s was a multi-millionaire with serious political clout. In 1932, he went so far as to attend the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, working to secure Franklin D. Roosevelt the presidential nomination. “Can you imagine a gangland leader going to a Presidential convention and sharing a suite of rooms with one of the most important political leaders in New York City?” asks George Walsh, author of the seminal 1980 book on Costello and NY mayor William O’Dwyer, Public Enemies. “That was a sign of just how close Costello was to the political establishment.”

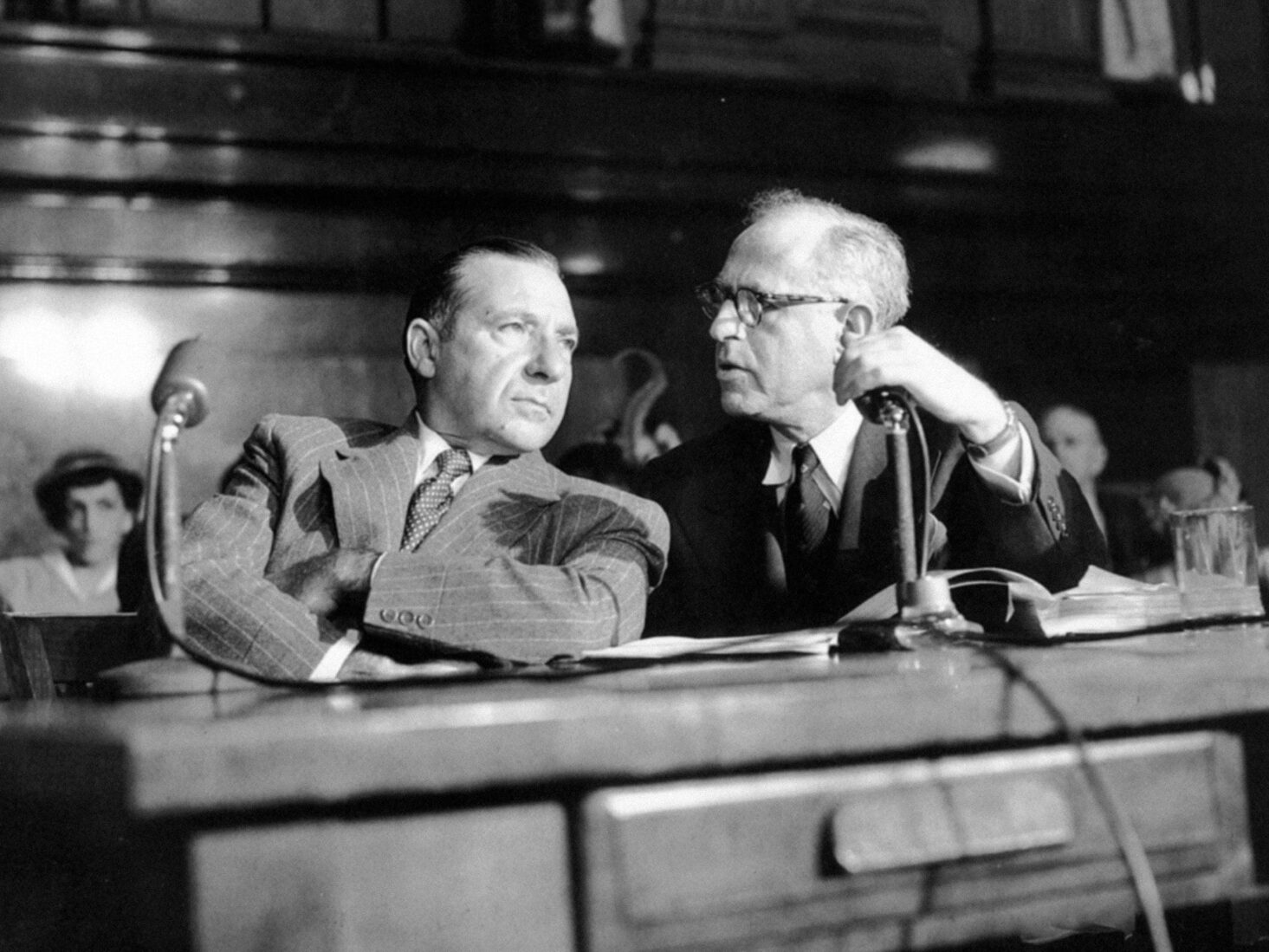

Yet even Costello’s political influence couldn’t help his boss, Lucky Luciano, often cited as the founding father of modern organised crime in the United States, who failed to live up to his moniker when he was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison in 1936 after being convicted of running a prostitution ring. With Lucky’s proposed successor Vito Genovese being charged with murder and fleeing to Italy, it was Costello who now stepped up from his role as ‘consigliere’ (advisor) within the Genovese crime family to become its acting boss. It was a succession that, in 1951, put Costello directly in the spotlight of the infamous Kefauver Hearings – a colossal Senate investigation into organised crime.

The hearings were televised; a medium that did Costello no favours. His deep, rasping voice (the result of having polyps burnt off his throat in a botched operation) made his voice seem to many Americans like a clichéd James Cagney-esque movie gangster brought to real life. Costello’s evasive, garbled responses, his demands that only his sweating, constantly wringing hands be filmed and his eventual decision to walk out of the hearings resulted in an 18-month prison sentence for contempt of the Senate. It would be the beginning of his downfall and the end of any serious attempt to quit the Mob and turn legitimate.

“Costello thought he could acquit himself well in his testimony, but it came out very poorly,” reflected DeStefano. “People came away shaking their heads and figuring, ‘Well this guy is doing something wrong or has done something wrong in life.’ He was never really allowed to shake the image. Even though you’re making your money legitimately, if you have that bad image, that reputation, it’s going to prevent you from being so-called legitimate.”

The Kefauver Hearings wouldn’t, however, be Costello’s most infamous moment in the national spotlight. Just like the Don Corleone character in The Godfather, in May 1957 a now elderly Costello was the victim of an assassination attempt that failed to kill him. Orchestrated by his rival Vito Genovese, who was vying for control of Lucky Luciano’s former empire, the two men’s inevitable clash had its roots in their vastly contrasting personalities.

Always keen to avoid violence, Costello was a cerebral character who lived a discreet life. Calling himself ‘Mr Schedule’, Costello dressed like an English gentleman. With his numerous Wall Street investments, and love of the steam room at The Biltmore Hotel, he was the very essence of a sophisticated corrupter rather than trigger-happy killer.

Genovese had a more impulsive, explosive personality and it was he who persuaded Vincent ‘The Chin’ Gigante to finish off his rival. Yet, astonishingly, the bullet Gigante fired clipped Costello’s skull but didn’t puncture it. It was a survival that bordered on the miraculous. As with Marlon Brando’s character, Costello took the assassination attempt as a warning and bowed out of Mob life in favour of retirement on Long Island, acting occasionally as a mediator and advisor for younger bosses such as Carlo Gambino.

Despite a lifetime upholding the omerta, Costello, now 82, began talking to crime author Peter Maas for a proposed biography, just at the time that Coppola was making the first of what would become the Godfather trilogy. Through the first few weeks of regular two- or three-hour long meetings with Maas, Costello revealed that Joseph P. Kennedy, father of the murdered President John F. Kennedy, wanted the Mob’s help in bringing alcohol into the USA. Kennedy was a major importer of whisky for more than a decade after the end of Prohibition and Costello claimed that he and Kennedy were in the liquor business together for “a time thereafter” – a claim that was later furiously denied by the late Kennedy’s family.

But Peter Maas’ book was never completed. Just weeks after recorded interviews began, Costello died of a heart attack, taking most of his secrets to the grave. There is speculation that an elderly Costello may have watched an early screening of The Godfather in the last year of his life. Did this influence his decision to finally go public with his memoirs? Nothing is certain. Yet Costello made headlines after his death in a way that utterly eclipses the low-key ending of the first Godfather movie.

In 1974, a full year after he was interred in the immense family mausoleum in the cemetery of St. Michael’s in Queens, a bomb seriously damaged the vault. Mobster Carmine Galante, recently released from jail on a narcotics conviction, was found to be behind the explosion. About to be anointed as the new boss of the rival Bonanno crime family, the bomb sent out a clear message as John Miller Jnr, Costello’s godson, explained in an interview given in the late 1990s: “This was his [Carmine’s] message, saying ‘all the old bets are off’. And Costello was the very definition of the old-style boss and the old ways. He shunned dealing narcotics, he believed in a certain code and this was Galante’s way of spitting in the face of the old ways.”

A more violent, chaotic chapter in the history of the New York Mob families was about to begin – and one that would see a gradual unravelling of the immense network of influence and control that the Mafia held over the highest echelons of politics and industry. Costello, not unlike Marlon Brando himself, was the last of a vanished generation.

As Peter Maas, whose torpedoed biography of Costello was never published, stated before his own death in 2001: “Costello was certainly the only major figure in the Mob who could have been a huge success legitimately. You keep hearing stories about how smart Mafia Dons are and what they could have done if they’d chosen another road. Costello is the only one who really could have done it.”

Read more: The scandalous story of Elvis and the illegal Dutchman