Hogarth and Europe: Wit, satire and social criticism shape Tate Britain’s latest retrospective

William Hogarth is finally receiving the spotlight he deserves - but does the Tate Britain’s latest show live up to its subject’s scathing sensibilities?

Here’s one you probably didn’t expect to see: William Hogarth’s satirical – and very politically incorrect – paintings and sketches displayed at the Tate Britain. They are presented for the first time alongside his contemporaries from around Europe, showing how public caricature and satire is not restricted to the Punch-and-Judies of little England. It’s a promising idea, but the exhibition actually ends up doing something quite different… and perhaps a little too predictable.

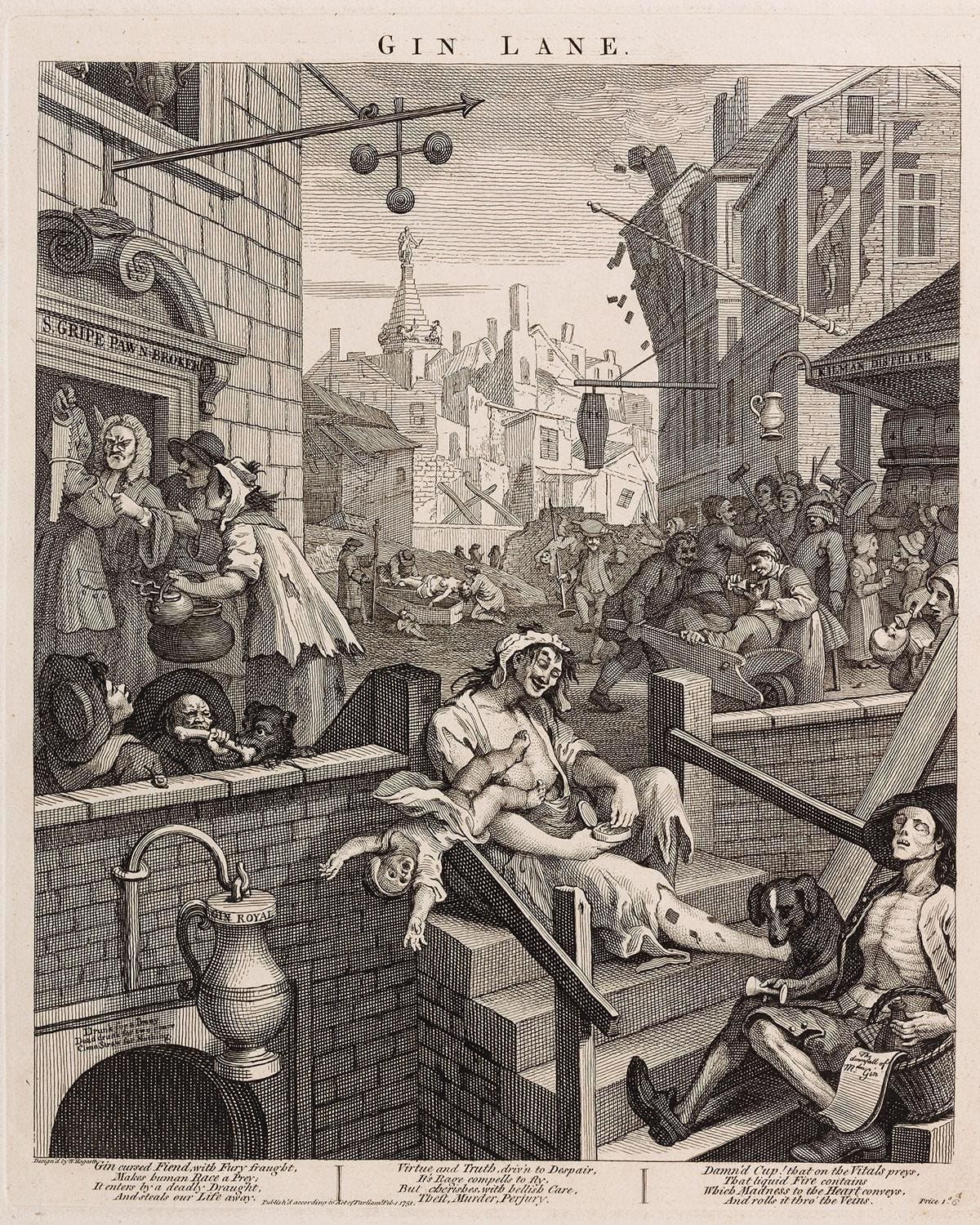

Hogarth is finally getting some overdue spotlight. He is the artistic equivalent of Swift, a social critic and satirist who presented the bawdy, sexual, vulgar, street life of his time: scenes that would establish the term Hogarthian. Born in London, to working-class parents in 1697, he began as an engraver before developing into a renowned wit, gaining him access to London’s arts scene. His work gained wide popularity throughout the rest of Europe, influencing his contemporaries before his death in 1764.

Of all these works, none became more famous than his ironically-named Modern Moral Subjects, a series of comic-strip paintings charting tragic lives in 18th century society. While otherwise available for viewing at The National Gallery (should you miss them) these remain the best examples of what Hogarth is about, and are served well by the presence of his other works – many sourced from private collections – and that of his contemporaries from Europe. Artists like Cornelis Troost, Chardin, Pietro Longhi, Crespi, and others offer a comparison between life abroad and here at home.

Those who love Hogarth appreciate his blend of boyish humour and grotesque caricatures. In the tradition of Pieter Brueghel, each artwork is a tableaux of modern life. You can spend an hour studying the terror in Southwark Fair, the viewer’s perspective in The Gate of Calais, or the visual cues from A Rake’s Progress. Questions abound as you get wrapped in a tornado of allegorical props. They arrive and are whisked away, replaced by smaller (or bigger) symbols the eye didn’t instantly meet. You begin questioning a drunk aristocrat’s line of sight. A Chinese ornament on a shelf. The blemishes on a prostitute’s lower lip.

One of the greatest pleasures of Hogarth is wondering whether these props mean nothing, or are the key to unlocking the painting’s narrative. The Tate’s notes guide the visitor well, pointing to areas we’re likely to miss. And even after seeing these works many, many times before, I still left having learned something new. Often, the painting’s are funny. But Hogarth’s work is also usually very sad; a dark, sometimes resentful, depiction of Georgian Britain. The sex workers and grease-lipped dandies that characterise his England are all there, but so too are other figures, like slaves.

The exhibition goes to great lengths to give these tragic figures some spotlight, offering insight into how they might have come to England. The gloomy aristocrats are made more vulgar as we spy the chained slave children waiting on them, and free black Britons are depicted as actors in social decay (groping a woman in Four Times of Day – Noon and debauched in A Rake’s Progress, plate 3).

Their important, and sobering, emphasis in the exhibition, as well as lectures on cultural appropriation, makes one wonder if it would have been more aptly called, ‘Hogarth, Europe, and Colonialism’. In fairness, the original theme runs a bit thin about three-quarters through. There’s blinding work by the Italian Guardi, the French Chardin, and the Dutch master Troost, to savour. And indeed, they are Europeans. But the parallels that this show promises, about Hogarth’s work and its juxtaposition with European artists, never gets deep enough. After watching each painting and reading the texts (and there are a lot of them) the curators have little more to say than this: street life everywhere else in Europe was a bit – but not completely – like street life in England.

The show segues into the exhibition’s more obvious mission: to analyse Hogarth as a person through the eyes of today’s politics. “He might have been a conservative,” one wall text implies apologetically, feeding us an impression of a mean jingoist. These texts, many of them written and sourced from contemporary academics, some from Stateside universities, are more concerned with ‘Whiteness’ – a modern, American political term whose use seems a bit of a reach here; aggrieved by the ethnic representation in 18th century Europe (one section even lists the demographic percentages of 1700s Paris).

|  |

Their moralising left a sour taste in my mouth, as did their flirtation with portraying Hogarth and his contemporaries as bad people for living 250 years ago. His art has always shown that it was a rotten time, as visitors can plainly see in Gin Lane and A Harlot’s Progress. We’re not stupid. You don’t need to read his paintings through the lens of Robin DiAngelo to step onto the Millbank and thank your stars for not having lived in Georgian England.

By focusing elsewhere, it misses what seems like an obvious approach. One that I think would’ve added more depth to the gathering of these artists, and their works, while allowing contemporary issues to slip in: looking at the continental struggles from Hogarth’s time, and considering our own recent history, what do we share in common as Europeans? The show isn’t really about Troost, Chardin, or Guardi. Nor is it about the people: the slums, or the fat-cat aristocrats in ruffs and powdered wigs. It’s often about today’s politics and Hogarth.

By the end, I had switched off from the theme, skipped the sanctimonious wall texts, and simply enjoyed the works for what they are: riotous, silly fun. Although one section describes his style as ‘lad humour’, that’s an amateur simplification. Hogarth’s humour has range, whether it’s his pug in a wig, or a gathering of red-faced men falling around a punch bowl (A Midnight Modern Conversation). Trying to make him too serious is this show’s biggest snag, and that also goes for his European friends. The masked-halls in Longhi’s The Ridotto of Venice, with its craning revellers in masks, the snoring market vendors in Paris, and the beer houses in Amsterdam (in which someone flashes their rear onto the street) have as much silliness as Hogarth’s London streets.

Often, that’s enough. A good experience is sometimes more than the curator’s intentions. So if you do go (and I think you should) read the guidebook, avoid the wall texts, and focus not on how Hogarth or his European contemporaries seem to us now, but what strange clues they left on their canvases about Europeans then.

Read more: Lenin, revolution and the hunt for the Fabergé Eggs