Salvador and Gala Dalí: Modern Art’s Most Famous Couples

“[Gala] was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife" - Salvador Dalí

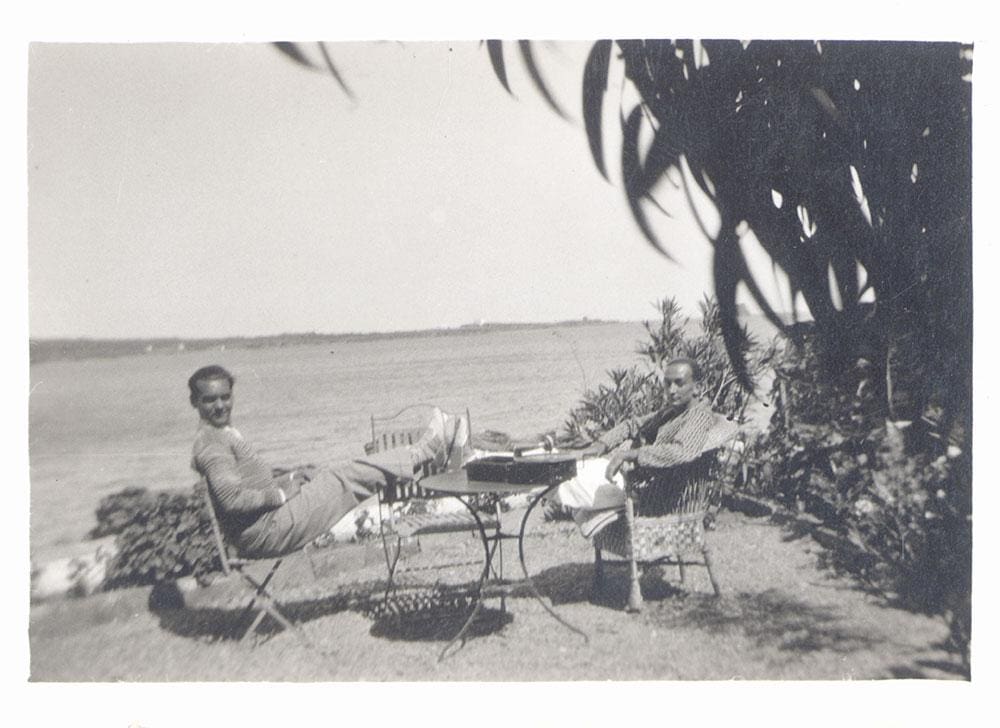

Federico Garcia Lorca and Salvador Dali in Cadaques

If Salvador Dalí wanted to see his wife, then he needed to write a letter first. Seeking permission in such a formal way in order to see one’s own spouse may seem unusual, but Gala and Salvador’s marriage was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a deeply unconventional one, not least in terms of written invitations. Gala has long been considered an arch manipulator of her husband, but her role in the renowned surrealist painter’s life is slowly beginning to be seen in a different, less negative light.

Modern Couples, a new exhibition at the Barbican, delves into the creative and personal relationships of modern art’s biggest names and how they inspired one another’s work, from Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso to Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

Gala’s influence on her husband’s art has long been apparent. From the early 1930s, Salvador signed his works with both their names. “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures”, he once stated. Salvador, however, was far from the first major artist who took this beguiling Russian, born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, as a galvanising inspiration. Sickly during childhood, young Diakonova was sent to a Swiss sanatorium at the age of 17, where she met Paul Éluard, the French poet who became her first husband.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait de femme,1938, Courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Paris

Living in Paris at the end of the First World War, the young Russian wife became immersed in the surrealist movement in which Paul, through works such as Répétitions, was a starring founder member. Her role was far from that of dutiful spouse, however, and she began an affair with Éluard’s friend and fellow surrealist artist Max Ernst, prompting Paul to run away to Saigon rather than confront the two lovers.

She brought him back to Europe, but the reunion was brief. It was in 1929, while the couple were on holiday in the Spanish town of Cadaqués and visiting the impressive, but still fairly unknown, Salvador, that their marriage broke down. “She was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife,” Salvador later wrote.

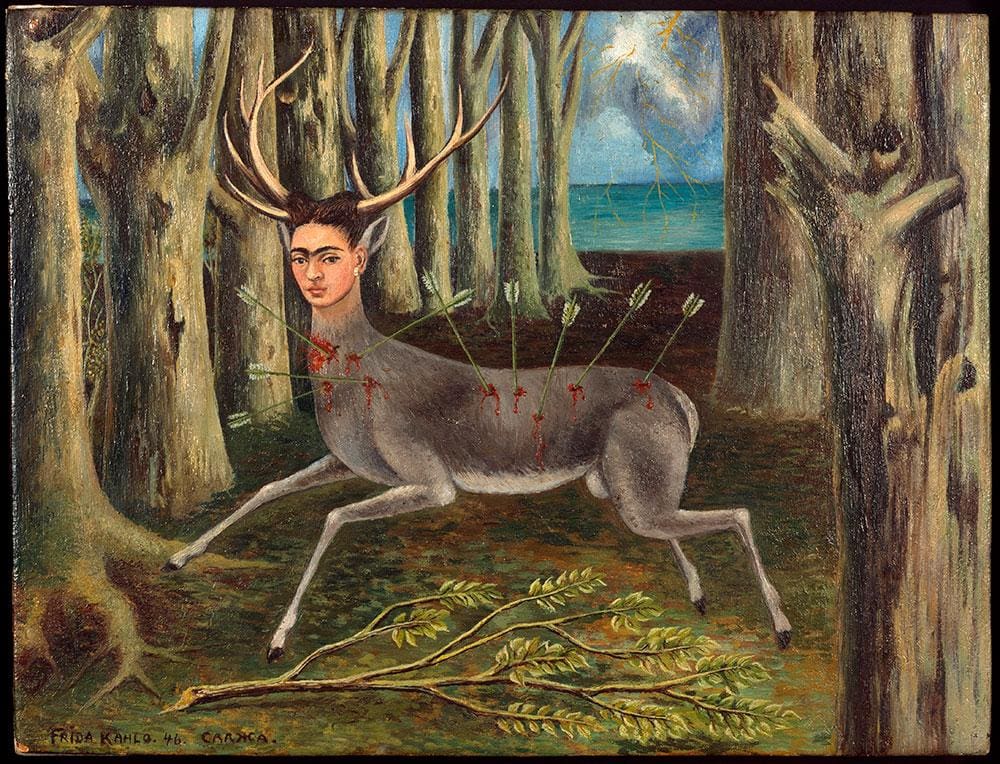

Frida Kahlo, Le Venadita (little deer), 1946, Photo Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

It is here that the reputation of Gala as a snobbish parasite begins to take shape. Stories of her reading tarot cards to determine her husband’s success, rumours of monstrous ego-driven temper tantrums and of a personality defined by money-grabbing shallowness all abounded during her lifetime, and have remained long after her death.

Yet there are holes in this narrative. Gala left her bohemian Parisian life for a fisherman’s house in Catalonia with an artist who was languishing in obscurity; hardly the choice of a woman fixated by material wealth. Also, her canny and adept skills as unofficial publicist and agent to Salvador impressed other artists immensely, to the point where Giorgio de Chirico, the Italian painter, asked her to become his agent, too.

Winifred Nicholson, Jake and Kate on the Isle of Wight, 1931, National Galleries of Scotland

Global success came to Salvador not long after their marriage. Mastering the art of the deal in terms of gaining huge sums for her husband’s works, Gala appeared in hundreds of Salvador’s paintings, often depicted as a deeply erotic, Madonna-like figure, such as the sprawling nude in Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, from 1944.

In Portrait of Gala with Two Lamb Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder, painted at the time of their marriage in 1934, Gala has her eyes closed, seemingly in a state of bliss and entirely at ease with the surreal chaos emerging around her. As far as domestic arrangements went, the bizarre written invitations that Gala demanded from her husband weren’t orders that were obeyed under duress – Salvador seemed more than happy to acquiesce to his wife’s wishes: “Sentimental rigor and distance as demonstrated by the neurotic ceremony of courtly love increase passion,” he wrote.

When Salvador was granted permission to see his wife, it was to the magical retreat of Púbol that he would visit: a remote castle that he bought for her and restored from its derelict state, complete with an interior he designed himself, encrusting the ceilings with a coat of arms bearing the letter G.

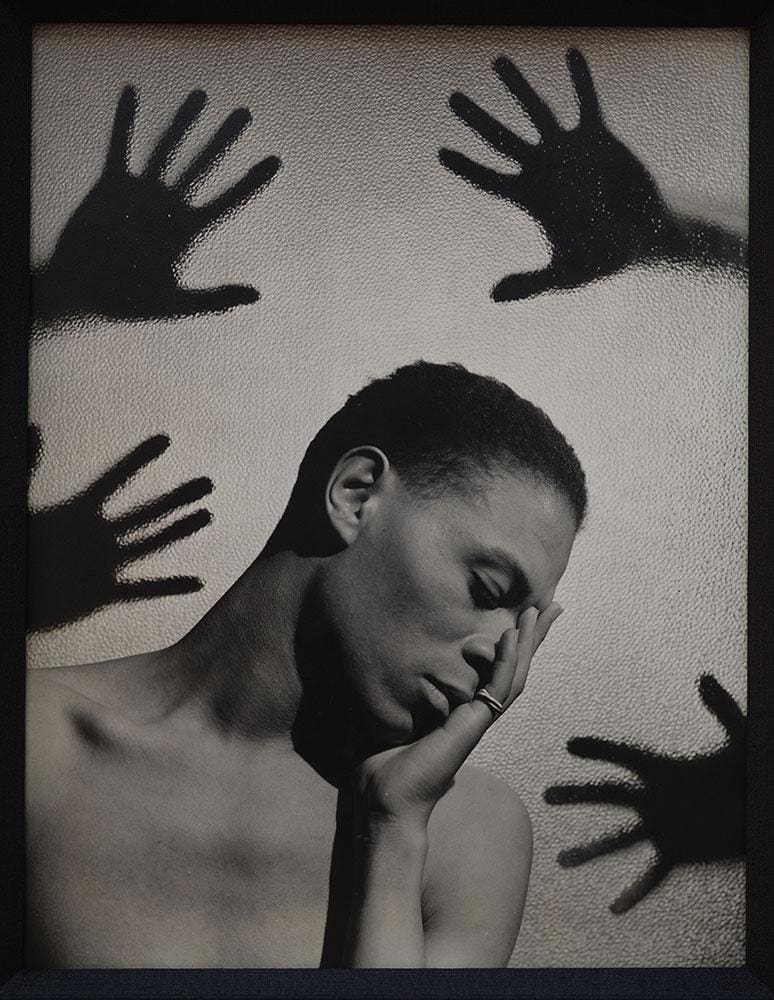

George Platt Lynes, James Leslie Daniels, c.1937, Courtesy of Beth Rudin DeWoody

Romantic to the core though Salvador may have been, the couple’s relationship would appear to have leaned more towards a mother-son dynamic. That, at least, is the conclusion of Dr Zoltan Kovary, a Hungarian clinical psychologist who wrote an analysis of Dalí’s artwork called The Enigma of Desire: “Gala sometimes called Salvador, ‘my little son’. They never had a ‘real’ sexual relationship,” said Kovary. “Dalí, although Gala raised deep desires in him, had fear of physical contact.”

Many of Gala’s own artistic achievements have vanished without trace: none of her own paintings are believed to exist and no manuscript has ever been found of the novel that she was supposed to have written behind the walls of Púbol. As a fashion icon however, there is more that has survived. Her saturnine looks inspired the likes of Christian Dior and Elsa Schiaparelli to design clothes for her.

Tamara De Lempicka, Les Deux Amies, 1923, Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Geneve

When Gala died in 1982, her grieving husband had already built a crypt, with a double tomb and an opening between them so that they could, as the Dalí Universe says, “hold hands in the afterlife”.

A fire a short time after Gala’s death prompted Salvador to leave Púbol, however, and when he died in 1989 he was buried alone in his home town of Figueres, 25 miles away.

Gala’s legacy would almost certainly have displeased her. As she lies alone in the Púbol crypt, a stuffed giraffe next to her tomb, there is almost no public awareness of her role in turning the public perception of art into a pop brand (a concept seized on by artists such as Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst), tackling head on the notion of the starving artist in a garret (the Dalís’ wealth came from commercial tie-in’s with products such as Datsun cars and lollipop wrappers) and being one of the very few women to have influenced the surrealist movement.

A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova descending from the airplane, 1926, Rodchenko and Stepanova Archives, Moscow

Púbol is now open the public, and visitors can see the ephemera of Gala’s life, ranging from her blue Cadillac to the crown made for her by Salvador from bent dining forks.

Perhaps the most poignant memory of Gala’s life, however is not one of her husband’s creations, but an undated note, written in French in her own hand. “Yes it is believed that I am a fortress, well defended and perfectly organised,” she wrote, “when at best I might be a small blinking tower that, through modesty, tries to cover itself and conceal its by now deteriorated walls to find a little solitude.”

£16, until 27 January, Modern Couples, Barbican Centre Silk Street, EC1Y, www.barbican.org.uk