Yeast jumpers and seaweed T-shirts: Why bio-textiles are the future of fashion

Would you wear a jacket made of milk protein, or a pair of trousers constructed from algae? As the fashion industry fails to wean itself off fossil fuels, prepare to acclimatise to some unlikely bio-textiles

When Charlotte McCurdy was confronted with the sobering fact that more than 60 per cent of textiles are made from fossil fuels, she decided that there must be – there had to be – an alternative. The California-based industrial designer, who now works at Stanford University’s Design School, set about developing a water-resistant raincoat made not from plastic, but from algae.

“The idea of sustainability in fashion is still trapped within an industrialisation framework – it’s about using fewer fossil fuels, or in a different way, and that’s not going to work,” says McCurdy, who, since the raincoat, has worked with fashion designer Phillip Lim to develop a dress made of the same plastic-like material, right down to creating the first algae-based, biodegradable sequins. “We need to be considering materials that at least have the potential to be carbon negative.”

McCurdy is not alone in exploring the potential of bio-textiles, as they’re called. New York-based biomaterials research company AlgiKnit, for example, is developing compostable yarns from biopolymers that can be turned into textiles. It uses kelp – a brown seaweed that’s already used as an emulsifying agent in foods and cosmetics, but which also happens to be one of the fastest-growing organisms on Earth – to create a yarn that is strong and elastic enough to be knitted by hand or machine.

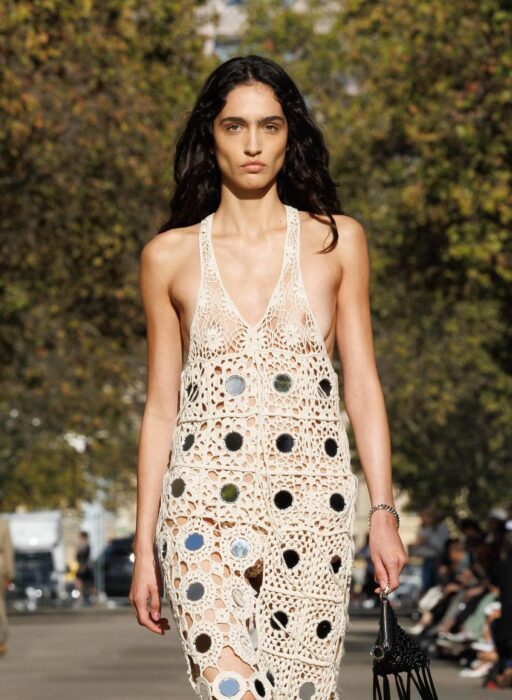

Stella McCartney x Keel Labs at Paris Fashion Week. Image: Isodore Montag

A prototype wallet crafted with Modern Synthesis’ bacteria cellulose-based textile, demonstrating the biomaterial’s viability for accessories and product applications.

Keel Labs is another start-up producing bio-textiles; in this case, a soft, smooth fibre it calls Kelsun, made from the abundant natural biopolymer found in seaweed. Roya Aghighi, a Toronto-based ‘design investigator’, has developed Biogarmentry, a proof-of-concept clothing textile made from algae that actually turns carbon dioxide into oxygen via photosynthesis. To make the textile, a single-cell green algae is spun together with nano polymers, the resulting cloth being bonded to form a garment.

The approach to clothing that Biogarmentary proposes is radical: each of its garments, which are in some sense ‘alive’, has a life cycle of a few months, before being composted. “We don’t typically think deeply about our clothing,” Aghighi says. “I think we’d be less likely to toss a shirt that was ‘alive’ into the washing machine or closet. We’d have to tend to it. It would be a dependent being, like your house plants or pets. And, just as people don’t tend to have 10 pets, you may be inclined to cherish the one or two living garments that you have, rather than over-consume.”

It’s not just algae and seaweed paving the path to bio-textiles. Bio-design technology company Modern Meadow has found a way of fermenting yeast cells to make a product that closely imitates leather. Anke Domaske, a microbiologist based in Hanover, has developed a fibre called QMilk by processing the casein protein in the cow’s milk deemed unfit for human production – some 1.9 million tonnes of it is produced each year in Germany alone.

In fact, says Domaske, her technology is an update of a method first developed in the 1930s, which was discontinued in favour of the ease and low cost of polyester. Like many potential bio-textiles, QMilk has various promising properties: while it can be turned into 100 per cent milk-based cloth, it also blends invisibly with wool or silk; it wicks moisture and is temperature regulating; it has the tensile strength of wool; and it’s both inflammable – and could thus be used in upholstery – and anti-bacterial.

“There are plenty of old, forgotten notions like this out there that need to be revisited,” says Domaske. “As a society, we use a lot of chemicals, but don’t look into the benefits of natural products already there. Or, we don’t think enough about the potential of waste products as a resource of value – it just needs to be explored.”

So far, so tempting, and the list of possibilities goes on: Jen Keane – ex-materials designer for Adidas and co-founder of textiles company Modern Synthesis – has developed a form of ‘microbial weaving’ using a specific strain of bacterial cellulose to create a strong, lightweight and fully recyclable hybrid material that is grown, rather than spun or woven. One of her test samples, a single-piece shoe upper, demonstrates this new approach – one which, she argues, also circumvents the problem of plant-based textiles (that growing the necessary plants may not be the best use of land or energy).

“We need to work with biology to develop textiles, to think about new ways in which textiles can be made – that approach has seen a huge growth in bio-textiles over the last three years,” explains Keane. “Now, every major brand is making a public statement about reducing their environmental impact through better raw material choices, where a lot of that impact happens. There’s now a wide variety of different bio-textiles, but we need to be able to scale up so we can make these new materials at prices that make sense.”

As Keane observes, there’s a bottleneck approaching: if every bio-textile start-up scaled up, the production still wouldn’t come close to meeting the demand of the fashion industry. And that’s not the only hurdle. McCurdy adds that, while the industry has a long history of being at the forefront of technology, from weaving during the Industrial Revolution to modern computing, bio-textiles have struggled to get backing from venture capitalists or major fashion companies. Although it bodes well that AlgiKnit secured $13 million in funding last year, she still laments that “it’s still just so much easier to [get funding] for some kind of software project”.

Then there’s the question of acceptance – that, undoubtedly, the prospect of wearing bacteria might be a turn-off for some. Keane points out that many of the fibres we wear today have been around for centuries, and a shift in public consciousness will be required to appreciate bio-textiles. “It has certainly been a concern among brands that people wouldn’t be comfortable with the idea of, for example, wearing a microbial-based cloth, even though yoghurt is a live culture, and we eat that!” she laughs. “We will need to not think about bio-textiles as alternatives, but as completely new kinds of textile.”

We may not have the luxury of squeamishness. The fashion industry is responsible for the production of up to 10 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions, and one fifth of the 300 million tons of plastic that we produce each year, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. We’re going to have to start thinking about what we consume, and how, sooner rather than later. It looks like yeast jumpers and seaweed T-shirts might soon be in vogue.