The business of doing good: Is philanthropy the future for luxury brands?

A new crop of sustainably- and socially-minded businesses are sweeping the UK’s luxury landscape – and may just have the power to change the way companies operate for good

In her 2021 book Rebuild, British retail maven Mary Portas set out the principles for what she termed the ‘kindness economy’. The idea, she explained, was that for businesses to thrive in a world becoming increasingly concerned with the environmental and social impact of industry, they must make transparency, ethics, respect and the larger implications of their practices as central to their models as profits and shareholder contentment.

Which sounds great on paper but, here we are in 2023, living in a world where greenwashing is rife, fast fashion has never been more popular and luxury brands routinely destroy their goods in order to maintain exclusivity. According to 2021 studies by First Insight and DoSomething, more than 70 per cent of Generation Z (who are set to account for 40 per cent of luxury shoppers by 2035) would be willing to pay more for goods from brands that guarantee sustainability and ethical production – but many companies don’t seem to have received the memo.

There are, of course, notable exceptions. Brands such as Patagonia, Allbirds, Gabriela Hearst and Stella McCartney have long worn their eco-conscious credentials on their sleeves via certifications such as B Corp status. New legislation, like banning the sale of new cars with combustible engines after 2035, is also forcing manufacturers to think about greener ways of doing business.

At present, however, this is very much the exception rather than the rule, with the majority merely gesturing towards sustainability and ethics via special collaborations or one-off collections. But a new wave of brands is setting out to change all that.

“We were struck by how most big businesses were run, how little was given back, and by their sheer lack of responsibility. Big businesses control governments by lobbying and this decision-making often negatively impacts us and the planet,” says Shafiq Hassan, co-founder of Ninety Percent. “We imagined a business model where the core ethos is on a positive change from the start, rather than what happens in the end. A model that is inherently built on the premise of giving back, empathy, gratitude, sharing and empowering with its profits.”

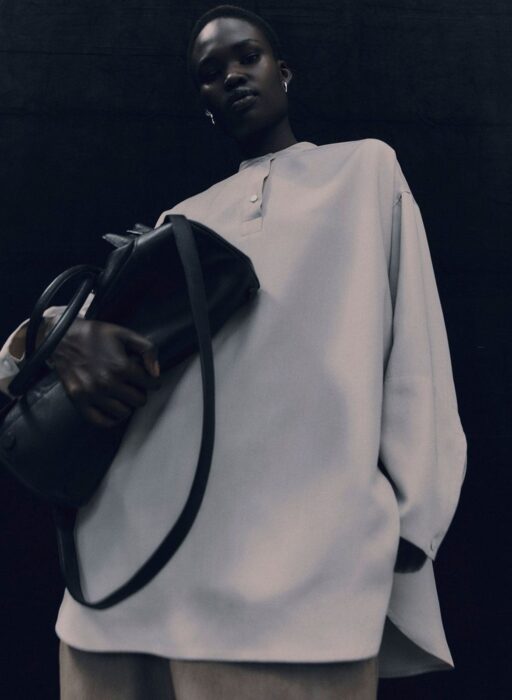

Image: Ninety Percent

Image: Ninety Percent

The solution Hassan and co-founder Para Hamilton devised was a fashion business in which 90 per cent of all profits would be shared among the individuals working within its supply chain alongside social and environmental causes. Promising your shareholders just 10 per cent of the returns on their investment is a bold move but, with the label celebrating more than a decade in business this year, it’s one that appears to be working.

Strikingly, in a system that has for so long been run by a practically uniform capitalist method of doing business, this is just one of myriad different philanthropic business models emerging as options for the future of commerce. In London alone, there are brands such as Maker’s Cabinet, which is tackling the problem of in-built obsolescence with its ‘Made for a lifetime or more’ promise, and Goldfinger, which makes bespoke furniture using locally-sourced, sustainably-grown wood (astonishingly, the UK is the second largest importer of timber in the world) while also offering community craft workshops, apprenticeship programmes and a People’s Kitchen charitable initiative.

Then there are companies like Earnt which are attempting to take money out of the equation altogether. Founded by Lauren Scott Harris and Lavina Liyanage in 2022, Earnt hosts charitable events, such as litter picking, beach cleans and community food deliveries, which earn volunteers access to exclusive events, discounts and limited-edition collections from luxury brands and hospitality venues.

“The idea [is to] normalise doing something in order to get something. Many brands do philanthropic activities, but no one has done it quite like this in such a tangible way,” explains Scott Harris. “In the past, luxury brands would have been nervous to be associated with something like a litter pick (there is nothing luxury about picking litter) but increasingly they are aware that we all share the responsibility to help where we can and that no one is too important to lend a hand.”

To date, Earnt has worked with businesses including Soho House, Desmond & Dempsey and Summerill & Bishop, with recent events – such as a river clean up which gained volunteers access to VIP bookings and a special lunch menu at The River Cafe – attracting a 600 strong waiting list. “What is also great is we see people who came to our first event signing up for all subsequent ones. Most of our events get booked out in a matter of minutes so there is also a lovely community of Earnt consumers that we are building,” adds Scott Harris.

The appeal of combining philanthropy with profit-making business is also catching on in the reverse as well. Earlier this year, the Princess Grace Foundation launched Grace de Monaco – a for-profit enterprise offering fine fragrances, silk scarves and homewares – at Harrods. The difference being, instead of proceeds going to shareholders they are donated directly to funding the foundation’s work supporting emerging artists in dance, theatre and film.

Image: Grace de Monaco

Image: Grace de Monaco

“It was time for us to reimagine and think creatively about how to connect with new audiences while staying true to her legacy of challenging the status quo,” says Grace de Monaco CEO, Claudia Poccia. “Grace Kelly was known in her life as a Hollywood icon, Princess of Monaco, and a fashion icon. Creating a luxury Maison in her name felt like the logical continuation of her story. It was in that spirit that we pioneered a luxury-for-good business model – the first luxury label to donate 100 per cent of its profits to a non-profit foundation.”

The hope, explains Poccia, is that Grace de Monaco will ensure the longevity of the Princess Grace Foundation without the need to rely on public generosity or major donations. Which, in turn, asks the question: as valiant as the efforts of these companies are, do any of them really have the answer to upending traditional business models?

Ninety Percent’s Hassan certainly believes so. “Our model can’t hinder growth as it is a business – all we are suggesting is that the shareholders will not pocket all of the profits but share 90 per cent with people in our supply chain and social and environmental causes we care about.”

“The traditional business model believes in making the most profit to maximise shareholder value. If our business is a success, change may happen and the word will really spread, challenging traditional businesses to rethink. The fashion industry, like all other big businesses, needs to be challenged to think differently.”

Equally, Earnt’s Scott Harris believes the flat fee it charges brands to organise and execute events becomes a no-brainer once they see the impact they can have. “It’s been really exciting to see how leader brands get the idea so quickly – and want to participate when they realise the power they have to influence behaviour,” she says. “We want the platform to be global so that, for example, you can get off the Eurostar and decide that you want to earn your queue jump at the Louvre by participating in a litter pick on the Seine that morning.”

The reality, says Hassan, is that while centring your business model around philanthropy may present challenges, in the future it may no longer be a question of choice. “Ultimately, life on earth is dependent on us all slowing down, that the bottom line being growth in profits can no longer be prioritised over the loss of biodiversity and human suffering,” he says.

“Taking responsibility and prioritising the planet and people should become an inherent way in which businesses are run. Companies should add positive impact to their bottom line and focus on doing good and implementing better practices.”

Mary Portas would be proud.