Lip sofas & lobster telephones: How surrealism made it into the home

A new exhibition at the design museum explores how one of the 20th century’s most influential movements impacted furniture, fashion and fantastical homeware

“A chair may serve many uses, though not necessarily that of sitting down,” wrote Salvador Dalí. Critics of the master of surrealism could have easily subverted this famous quotation to read ‘art may serve many uses, though not necessarily that of losing money’.

The man nicknamed ‘Avida Dollars’ (‘Greedy Dollars’) by André Breton, one of the founders of the Surrealism movement, was something of an expert in earning the chagrin of his fellow artists in the fulcrum of the movement that confused, shocked and entertained the art world in equal measure from its inception in the 1920s. But what Dalí lost in respect from his fellow artists, he gained in commercial revenue, paving the way for surrealist art forms to be taken out of galleries and into people’s homes.

This autumn, the new Design Museum exhibition, Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today, features, in a move that is almost obligatory to draw the crowds, one of the four extant Lobster Telephones created by Salvador Dalí. “I do not understand why, when I ask for grilled lobster in a restaurant, I am never served cooked telephone,” he once remarked; the comments of a man who had long since decided that art and everyday life were one and the same thing.

Yet the Lobster Telephone, as funny, blunt and incongruous now as it was 86 years ago, was never destined to be seen anywhere other than an art gallery. Indeed, if early viewers of the work were shocked, they were actually being let off lightly. Dalí’s original intentions were to create a telephone placed on top of a live turtle or to have a phone covered in dogs’ noses with the extra delight of a dead rat stuffed inside the receiver. At around the same time, Man Ray was creating a laundry iron with large nails poking out of it and Méret Oppenheim made a cup and saucer covered in gazelle hair.

![Wall plates no. 116 from the series Tema e Variazioni [Theme and Variations], after 1950, Piero Fornasetti, Silk print on porcelain](https://luxurylondon.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Piero-Fornasetti-wall-plates-no-116-from-Tema-E-Variazioni-640x0-c-default.jpg)

Wall plates no. 116 from the series Tema e Variazioni [Theme and Variations], after 1950, Piero Fornasetti, Silk print on porcelain. Fornasetti Archive

Salvador Dalí’s ‘Mae West Lips sofa’ at a preview of Christie’s Modern British Art and Impressionist and Modern Art, 13 June 2019

So far, so surreal and defiantly and definitely unusable in an ‘everyday’ environment. Yet Dalí’s surrealist experiments, it should be stressed, did use something approaching ‘ordinary’ items conjoined together for the first time – presuming, that is, you count lobster as a standard item on your shopping list.

Twelve years before Dalí made his Lobster Telephone, opprobrium was already in motion about the supposed commercialisation of Surrealism. The word itself had only been invented in 1917 by the French poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, but, by 1924, the avant-garde were already losing the battle for artistic purity. The Paris premiere of Max Ernst and Joan Miró’s surrealist-influenced stage designs for a production of Romeo and Juliet performed by Serge Diaghilev’s ballet company, Ballets Russes, was ruined by André Breton and other Surrealist founders blowing whistles and invading the stage during the performance to proclaim their disgust with what they considered a radical avant-garde movement selling out to crass commerce in a mainstream theatre.

But their efforts were in vain; particularly when someone as money- and fame-obsessed as Dalí entered the scene. For it was he who, more than any other Surrealist artist, understood that no art form can remain in purist aspic without it swiftly becoming stagnant. By taking surrealist art out of the revolutionary arms race, his work for commercial clients took the form in a new direction.

From the battlefields of artistic authenticity, surrealism, surprisingly, went home and had a lie down on a particularly original looking sofa – also on display at the Design Museum show. This creation by Dalí has since become one of the most recognisable pieces of art created in the entire 20th century.

Created for Edward James, a self-confessed eccentric who inherited the immense West Dean Park estate in Sussex, Dalí set about turning his wealthy customer’s Edwin-Lutyens-designed shooting lodge (known as Monktons) into a temple of surrealist art that could actually be switched on and sat on. The pink satin and red velvet ‘lips’ sofa, named ‘Mae West’ after the sexually provocative movie star, sat alongside a white grand piano that rose from a pond and gushed water from its keyboard, and chairs whose backs were shaped as arms and hands entwined together. James may have been one of Dalí’s most loyal customers but even he decided not to take up the Catalonian on his offer to create a table made of egg whites and walls that would move in and out in a manner designed to be reminiscent of a dog’s stomach.

By the 1940s, fashion and advertising was already using avant-garde surrealism in commercial campaigns, with Dalí, naturally, at the forefront. After making chinaware for Royal Crown Derby, he created a window display for the vast New York department store, Bonwit Teller.

As scorn for Dalí from the ‘purists’ of Surrealism reached apoplectic levels, other artists ventured into commercial collaborations without damaging their reputations among the zealots of Surrealism. Man Ray, for one, became a highly successful fashion photographer, directing shoots for Vanity Fair, French Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, while Breton, the man who started the whole shebang, seemed to forget his Romeo and Juliet ballet performance protests when he considered (and then aborted) a desire to set up a surrealist brand to rival Paramount Pictures.

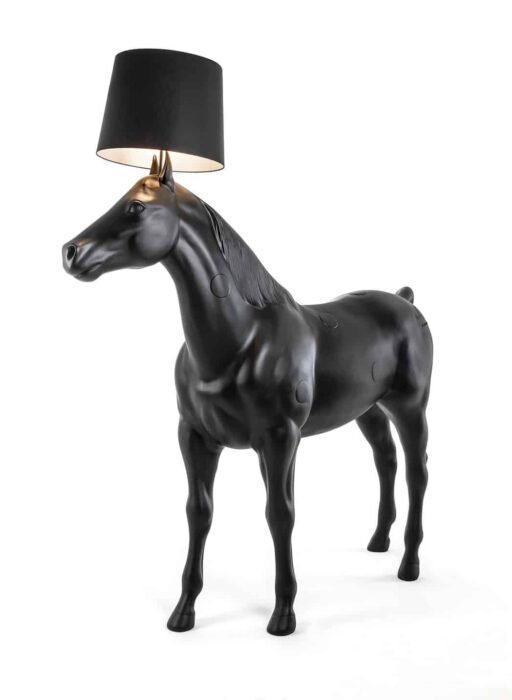

‘Horse Lamp’, 2006, Front Design, Manufactured by Moooi BV, Breda /Niederlande, Plastic; metal. Vitra Design MuseumPorca Miseria!, 2019 edition of 1994 design, Ingo Maurer, Steel; porcelain. Vitra Design Museum

‘Hand Chair’, about 1962, Pedro Friedeberg, Production this copy: c. 1965, Carved mahogany. Vitra Design Museum

‘BLESSbeauty Hairbrush’, 2019 edition of 1999 design, Bless, Beech; human hair. Vitra Design Museum

Though, for Dalí at least, taking Surrealism into the mainstream worlds of advertising and home furniture wasn’t entirely a seamless journey into an ocean of lucrative paydays. When Dalí discovered that Bonwit Teller had “respectabilized” his display in the Manhattan department store window, he smashed his way through the glass in rage, getting himself arrested for his troubles.

Almost a century on from its creative high-water mark, Surrealism has had a bumpy ride in what have become sporadic forays into popular culture. Pop Art in the 1960s took plenty of inspiration from Surrealism and the 1980s saw a kitschier revival with the post-modern take on Surrealism. Both eras were defined by playful excess and a deep wealth of underlying anxieties; exactly the social and political atmosphere in which the movement’s ideas work most effectively. Yet, fast forward to 2022 – to an environment infinitely more serious, woke and traumatised – and the surrealist legacy lives on, most strongly, perhaps, in the works of the star-chitect Philippe Starck.

At the planned Maison Heler hotel in the French town of Metz, Starck’s 14-storey, out-of-scale phantasmagoric hotel promises to create a ‘habitable, surreal and poetic work of art’. His transparent Perspex remake of a Louis XVI armchair, or the leggy Juicy Salif lemon squeezer he designed for Alessi, are both utterly confusing and amusing designs. You don’t have to look hard to see the leaf that Starck is continuing to take from the original Breton-penned Surrealist manifesto, which laid out the foundations for a desire to access a deeper reality by trying to bypass the intellect, tapping into dream states and the irrational part of the psyche.

As for Surrealism’s most famous exponent, Dalí declared the death of the movement at a New York gallery show of his own in 1941, before going on to embrace Catholicism and battle increasing bouts of depression. Derided by the true believers of the movement, it was, ultimately, the Spaniard with the waxed moustache who came to understand the limitations of Surrealism and the potential it still has to allure both the radical and the reactionary in every form of art.

“Surrealism is destructive,’ Dalí once said. “But it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision.”

‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design’ runs at the Design Museum from 14 October 2022 to 19 February 2023, designmuseum.org