Ahead of their time: John and David Silver on the art of dealing vintage Rolexes

For 25 years – way before pre-owned watches became big business – father-and-son team John and David Silver have been selling vintage Rolexes through their store in Burlington Arcade. A new book charts their story in

David Silver needs a very large safe. Every evening, when the family business in Piccadilly’s Burlington Arcade closes, he puts away a few hundred Rolexes that are valued in the millions. But then the Vintage Watch Company, a business founded by his father 25 years go in 1995, probably owns the world’s largest collection of vintage Rolexes, dating from the 1940s through to the 90s.

“Funnily enough, I’m not really a watch guy,” Silver chuckles. “None of us [in the store] can get particularly excited about tourbillons, for example. But we do love the designs of these watches. We’re retailers first and foremost. We just happen to sell old Rolexes.”

The business came about when John Silver, David’s father, realised the potential of focusing on one product. He had owned a chain of jewellery stores, which he sold to Debenhams, for whom he then worked briefly as a director. “Debenhams would speak of ‘critical mass’,” says David. “If they launched a handbag line, they didn’t do five styles, they did 55. And my dad thought he could offer critical mass with vintage Rolexes, to offer genuine breadth of choice. It also meant the pressure to sell the watches was off – much of our stock is steadily appreciating.”

When John Silver first turned to the fledgling vintage market, selling old jewellery and watches from a booth in Bond Street Antiques Centre, Rolex simply outsold everything else. Even back then, Rolex had something of a cult following. “Rolex is regularly talked about as being one of the top five brands in the world,” says Silver. “Not just among watch brands, but up there alongside the likes of Kellogg’s or Coca-Cola. Ask anyone anywhere in the world to name a watch brand and the majority will say ‘Rolex’. The company is simply brilliant at marketing. Early in its history it was building association with high-profile events and achievements that gave the name credibility.”

Not that Rolex devotees have merely been suckered in by clever advertising. Rolex can count among its output more than a few bona fide design classics – watch designs that are by some distance the most copied and counterfeited in the world. That’s why Silver has to vet every watch he buys in person, checking serial numbers and for the kind of sophisticated fakery that forgers use to try and pass off a valuable Daytona as a very valuable Daytona. The difference is often the subtlest of dial details. Silver will also politely decline any watch that isn’t 100 per cent original – that has had a dial replaced, for example, even if Rolex replaced it itself.

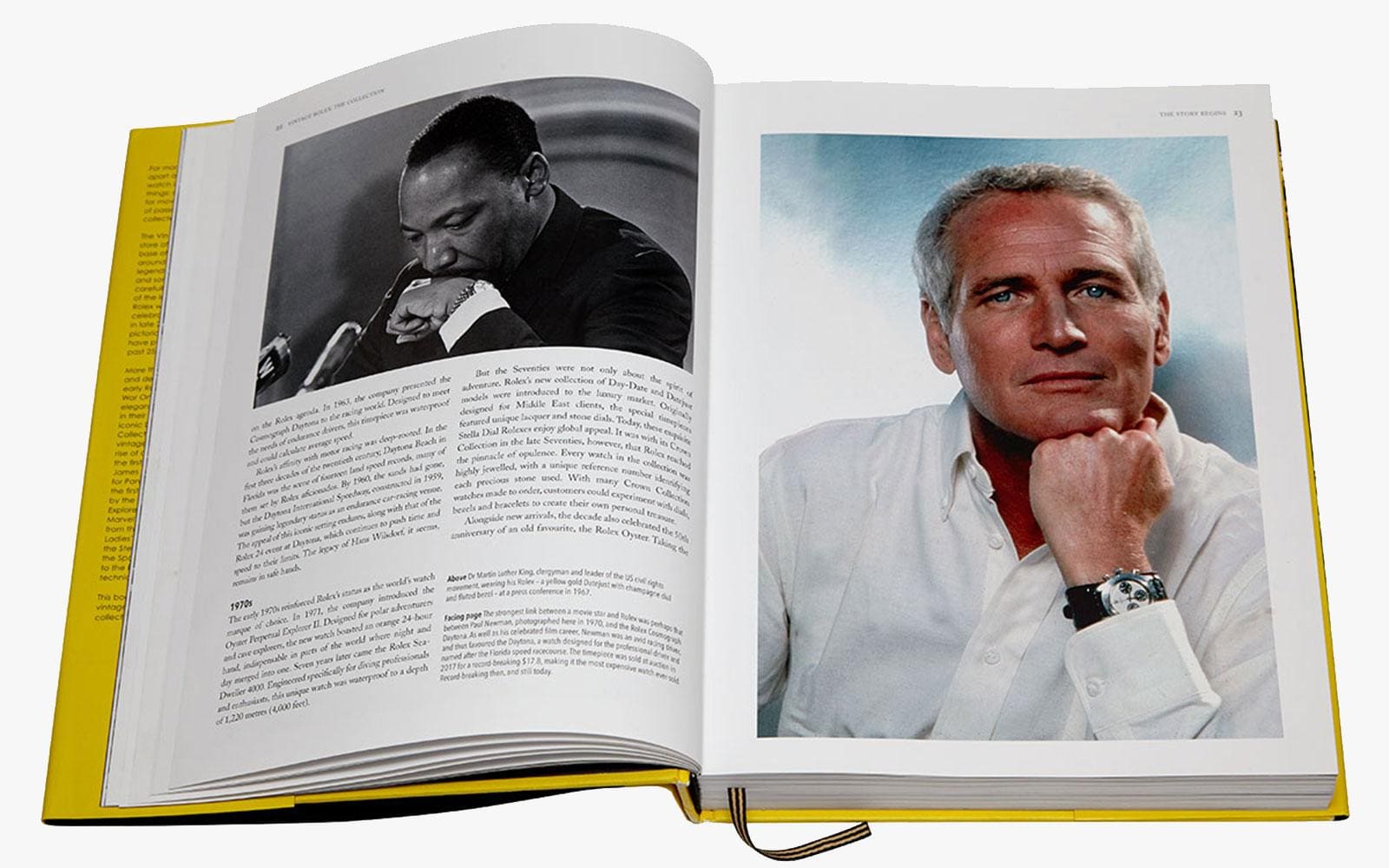

At the end of 2020, the Vintage Watch Company turned 25. It celebrated by publishing Vintage Rolex: The Largest Collection in the World. A catalogue of 1,800 watches that have passed through the company’s story, the coffee-table book is one of the largest pictorial records of vintage Rolexes ever printed. The Deluxe Edition (£125) is housed in a cloth-covered presentation box and ribbon.

In December 2020, a Rolex Daytona owned by Paul Newman – a gift from his wife with the inscription ‘Drive slowly, Joanne’ on its caseback – sold at a New York auction for $5,475,000. The most expensive Rolex ever sold – another Daytona bought for Newman by his wife – sold in 2017 for $17.8 million. What exactly is it about vintage Rolexes that makes them so sought-after?

“Rolex has had this ability to focus on a very clean style and functionality,” says David. “It’s not about complications. It’s about simplicity and usability. I think most people buy a Rolex for its classic styling, for the outside rather than the inside – though Rolex might well be horrified by that idea.”

Rolex itself has been an occasional customer of David’s, filling gaps in its archive. Most customers, David admits, tend not to be diehard horophiles and opt for a classic Oyster, often one produced in the year of their birth. “It’s a rite of passage purchase, something you keep for life,” says Silver.

Occasionally, however, someone is after something rather more special. “I remember selling my first Cosmograph, a gold pre-Daytona model,” Silver recalls. “It was coming up to Christmas and this guy paid £19,500, which back then was a serious amount of money. It was the most expensive watch we’d sold up until that point. I was physically shaking as I packaged it up for him.”

Alongside the Oysters, which start from around £4,000, and which the Vintage Watch Company buys from private sellers and the dealers around the world, are plenty of early Rolexes – “the kind of designs that most people wouldn’t typically even think of as being Rolex, the kind of thing we get excited about but not everybody does,” says Silver.

While some people are looking for a vintage watch in mint condition, other collectors, says Silver, prefer those that are showing signs of age – patina, fading and discolouration. “Some people can get very excited about idea of ‘pumpkin’ lume or a ‘tropical’ dial and love how distinctive and pretty a patina it can be. And, truth be told, some people are horrified by it – the idea of paying three times the normal rate for something that’s distressed makes no sense to them at all.”

Silver is cautious of holding any Rolex stock that is too rarefied for the broadly mainstream customer. As he stresses, he’s a retailer – he buys to sell. So while on occasion he may be offered a Rolex valued at, say, a cool £250,000 – “the kind of watch that invariably has to live in a safe,” he notes – he’s unlikely to buy it.

“That’s a lot of money to invest when we don’t know who might buy such a watch or when,” he explains, “and when for the same money we could buy 25 GMTs. We’ve never set out to be ‘the proud owner’ of a certain incredibly rare model. Never mind how rare the watch is – can we sell it? We don’t get emotional about the watches – there are plenty that on paper we shouldn’t have sold because of their subsequent increase in value. But that’s not retailing. And that’s my father’s discipline there.”

It’s why the company also keeps a close eye on what Rolex is doing with its new models – because where Rolex leads, the vintage Rolex market follows; if Rolex introduces a new Submariner, for example, there’s nearly always a demand for vintage Submariners soon afterwards. In part, Silver explains, that’s to do with Rolex’s distribution. Just because it has launched and advertised a new model, doesn’t mean you’ll be able to find one to buy.

“And in a world of instant gratification, that’s a problem for some customers,” laughs Silver. “But a new launch by Rolex also inspires interest in the original version, and powers demand for vintage models. Besides, there’s a certain character to vintage Rolexes. We’re a blip in the huge Rolex market, but I think we’re also a glorious representation of what Rolex has produced, of what is an amazing company.”

‘Vintage Rolex: The Largest Collection in the World’, Deluxe Edition is published by Pavilion, £125, pavilionbooks.com

Read more: The most interesting timepieces from Watches & Wonders 2021