Shaun Leane on Alexander McQueen and Era-Defining Jewellery

“In the early 90s, London was on fire. There was a creative energy. You used your medium, whatever it was, to provoke and inspire. I wanted a voice.”

1994. Britpop and Cool Britannia; Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit reign supreme. Indie scruffs are outselling manufactured boy bands, as Oasis, Pulp, Blur and Björk blare out of radios across the country. Weird artworks by mouthy young artists are becoming collectables, making millionaires of them in the process. Collections by Hussein Chalayan and Alexander McQueen will soon appear in Vogue as regularly as Chanel and Dior. The 90s was the decade in which “the left field became the mainstream,” declares The Telegraph.

In 1994, London was exciting, it was cool, and it was the year that a collaboration between two young friends proved a pivotal moment in both their careers. Two years earlier, Shaun Leane, an apprentice jeweller who had been mastering his craft in Hatton Garden for nearly a decade, had met one of Central Saint Martins’ most promising fashion students, out for drinks with a mutual friend in Soho. “He was shy and quiet, and different from everyone else,” says Leane. “We immediately became the best of friends – soul mates.” The man Leane is talking about was known as Lee to his friends. Alexander McQueen to the rest of us.

Kate Moss walking for Alexander McQueen (photography by Chris Moore)

Kate Moss walking for Alexander McQueen (photography by Chris Moore)

Leane was a conservative goldsmith and McQueen an avant-garde fashion designer. “I thought we were worlds apart,” Leane says. But McQueen visited his friend’s atelier – “very traditional, dim and Victorian, with leather skins and old tools” – and loved it. He suggested they work together on his next show. Leane laughed. McQueen didn’t see a lack of funds as a problem, suggesting they work in silver or brass, copper or feathers, or aluminium. “I’m a goldsmith… ” Leane protested. “I don’t think it’ll work.” But it did. “He made me think outside the box. The skills, the hunger, the fearlessness – it was all in there. Lee just opened the doors.”

Leane’s driver was already in evidence a decade earlier. Restless, frustrated, fed up with school, too young for college, he was propelled by a careers officer towards a year-long Youth Training Scheme that focused on jewellery design and metalwork. As a teenager, he was artistic, creative, into fashion; jewellery was “all right”, although the fact that he wore rings and earrings, often borrowing his mum and dad’s jewellery, may have made his calling clearer to this prescient careers officer.

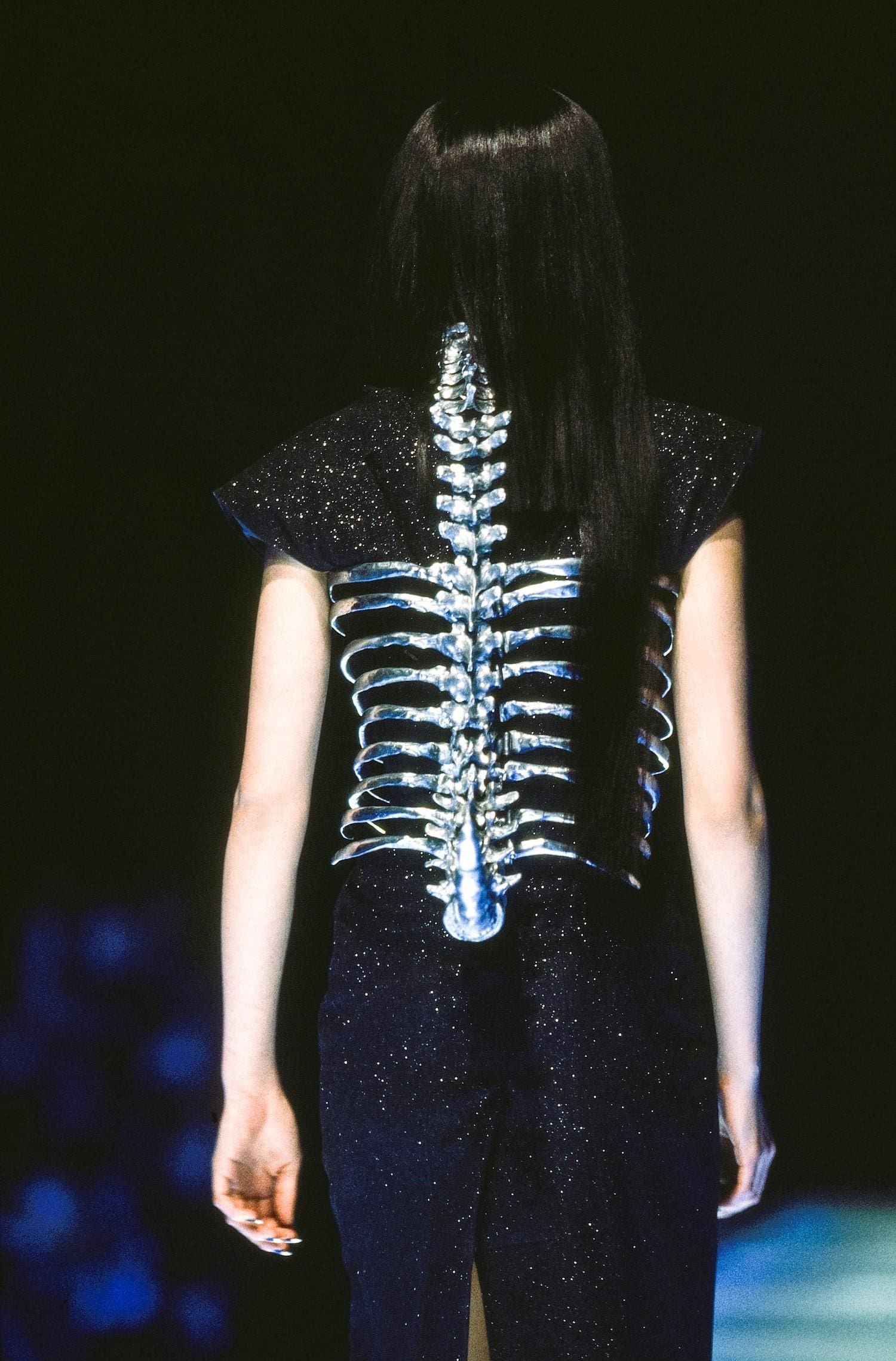

Photography Robert Fairer

Photography Robert Fairer

Leane completed his coursework in six months – with a distinction – and his tutor suggested a traditional goldsmithing apprenticeship. “Can you imagine? I’d just turned 15! ‘How long’s that then?’ I said. ‘Seven years – just do it for a year,’ my tutor said.” So this rebellious 15-year-old from Finsbury Park found himself at a wooden bench in Hatton Garden’s English Traditional Jewellery shop, flanked by two talented masters of the trade. His instructions were clear: “Start at eight, finish at six, sweep in the morning, and evening, for gold dust and diamonds, make our tea, get our lunch, speak only when spoken to.” This apprenticeship was the making of the young man. “I became a student who absorbed, listened, made, tamed by passion and education. I was 100 per cent engaged with something that I loved.” Leane completed his training and stayed with the company for another five years.

If ever there was a poster boy for the merits of apprenticeships, it’s Leane. This year marks 20 years since he set up his own company, and 35 years in the industry, all thanks to this intensive training at an early age. His distinctive jewellery pieces, for men and women, crafted in gold, silver and more unusual materials like black rhodium, are at once elegant and eccentric, classic and curious. Collections are named after the natural world’s prickliest inhabitants: rose thorns, serpents, sabres, quills. These are very different from the tiaras and fine jewellery Leane had been making and restoring for the most prestigious boutiques in Bond Street, and for royal families around the world. What gave him the impetus to pursue his own designs? “I wanted to create jewellery that was modern, that reflected the times we were living in,” he says. “In the early 90s, London was on fire. There was a creative energy. You used your medium, whatever it was, to provoke and inspire. I wanted a voice.”

His employers let him use their workshop in the evenings and at weekends and, with McQueen’s encouragement, Leane started to work on his own. His solid training in antique restoration and love of designs from the Victorian, Georgian and Art Deco periods – “close to each other but so distinctive; there’s such romance about the longevity of jewellery” – meant that classical, beautiful pieces remained his “bread and butter” while he created his own collections on the side. “During that time with Lee, I was finding my identity,” Leane says. “I respected him highly. He was a genius. When you saw him work, it was magic. And he said my work just blew him away.” It was an earring for McQueen’s The Hunger collection (1996) that launched Leane’s signature design. “He wanted one for each girl, something quite punk. I came up with the tusk – so elegant and refined, yet powerful and strong. I took a fine, beautiful line that created a powerful statement and I think that runs through my work today.”

Meghan Markle in Shaun Leane

Meghan Markle in Shaun Leane

Our conversation about the 90s always comes back to McQueen. Leane’s affection and admiration for him, and his enduring influence, is palpable. “We both came from apprenticeships and traditional training. We took our skill and referenced history, our heritage – we didn’t disregard or copy it – to create something new.” The year before the tusk earring, Leane made silver watch chains, inspired by Victorian fob watches, for his first collaboration with McQueen, on the acclaimed collection Highland Rape. The working arrangement: “You make stuff for my shows and I’ll give you clothes.”

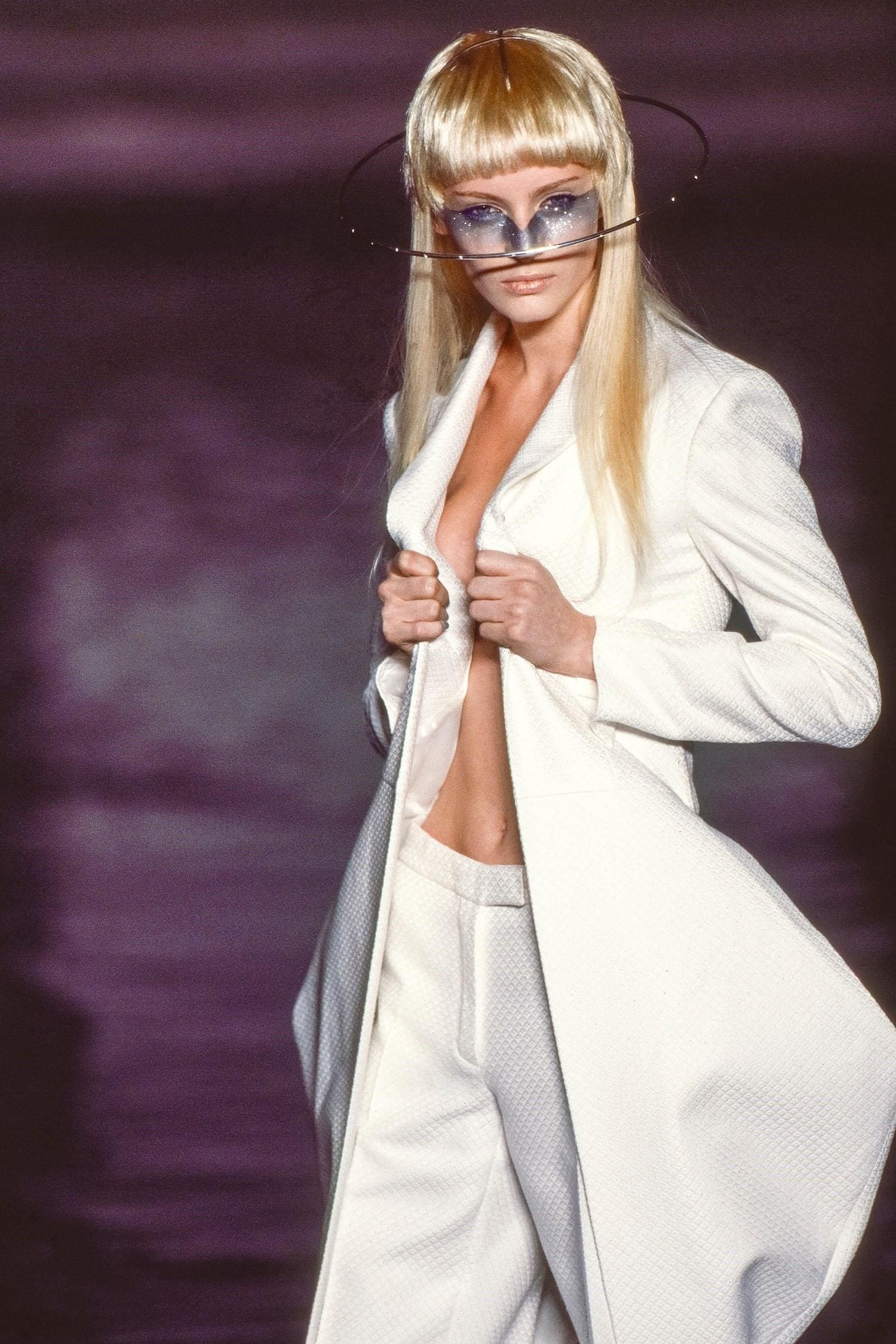

Photography Chris Moore

Photography Chris Moore

Thinking outside the box became the duo’s modus operandi, culminating in the aluminium coiled corset in 1999, one of the pieces that led Sotheby’s to describe Leane’s works as “antiques of the future” and which signified a move from jewellery into sculpture – quite the accolade for a man who had collected its auction house’s brochures as a young goldsmith. “It has the appearance of armour but a silhouette that shows the beauty, softness and curves of the female form. It is this delicate balance that defines that era of work,” Leane says. McQueen recognised the significance. “After the show he said, ‘We should sign this piece’”.

It was auctioned in 2017, along with 45 other bespoke works produced from 1995-2011 as part of Sotheby’s A Life of Luxury series. Another stand-out piece was the evening glove, modelled by Daphne Guinness. “It was a very important piece for me, because it was a combination of everything that represented the Shaun Leane house. It pushed design boundaries. No one had ever crafted an 18-carat white gold and diamond evening glove. It took five years to make; 14 craftsmen worked on it. It bridged high-end fine jewellery with fashion.” Subversive artistic challenges define Leane’s career. Perhaps because of this, he welcomes modern technology with open arms. “We were the second company in the UK to buy a 3D printing machine, about 17 years ago. The Royal College of Art bought the first one.”

You can find Leane’s work in the V&A jewellery and fashion galleries – his bejewelled yashmak went in after the Savage Beauty exhibition – and now also at Kensington’s 21 Young Street, where he’s created an asymmetric floral metalwork design for a new property development. He has adorned the external windows of its apartments with sculptures in bronze – “a classically beautiful material that ages so well” – that have been six years in the making. And he’s not just branching out into architecture. Leane has been signed by Pace Gallery as one of its artists and has a furniture deal and a project concerning “artwork in China” in the pipeline. I’ll expect to see these new pieces in an auction 20 years from now, I tell him. “The journey is beginning again,” Leane says, smiling.