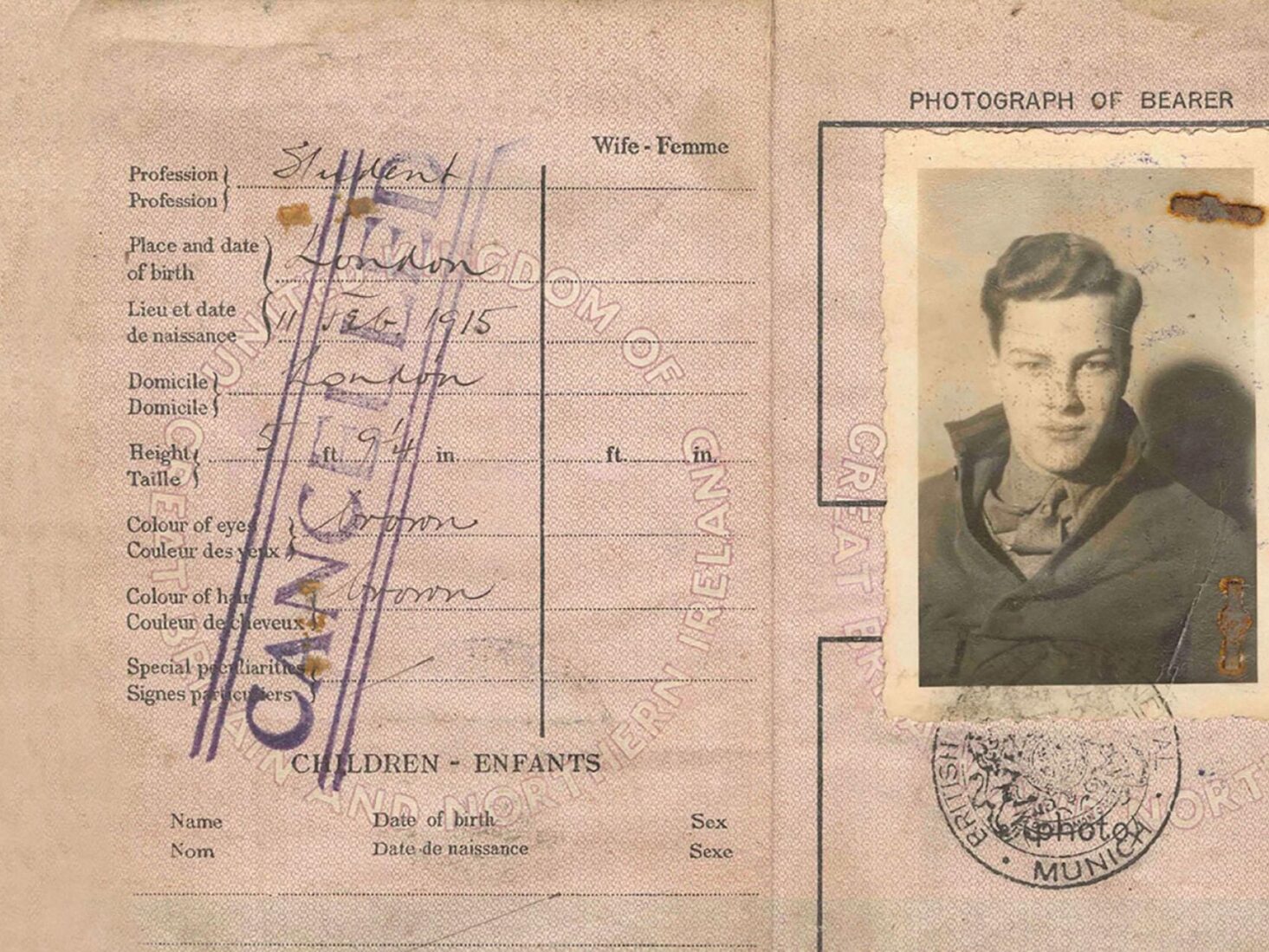

The Extraordinary Story of Travel Writer Patrick Leigh Fermor

For his high-spirited accounts of adventures around pre-war Europe, former special force’s officer Patrick Leigh Fermor is widely regarded as one of Britain’s best ever travel writers. A new book by Michael O’Sullivan explores how, through

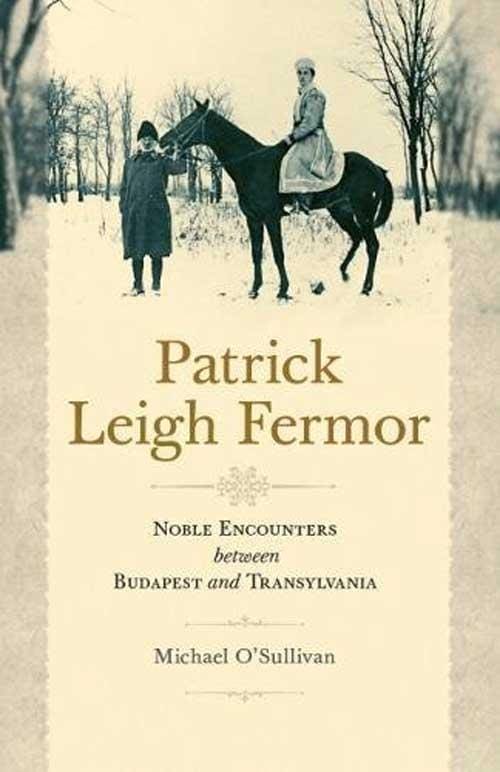

It’s odd that a man best known for walking across Europe is depicted on a horse on the cover of his own book about the journey. Now here is Patrick Leigh Fermor again on a horse, this time on the cover of Michael O’Sullivan’s recently released Noble Encounters Between Budapest and Transylvania – a fascinating new work of social archaeology about Leigh Fermor’s famous journey.

The horses seem a somewhat brazen inconsistency that appears to fit perfectly with Leigh Fermor’s approach to writing, which was to never allow the truth to mar a good story. And a good story in three parts is exactly what his classic account of walking from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul during the 1930s became – enshrined in A Time of Gifts, Between the Woods and the Water, and a final third instalment, The Broken Road, published posthumously.

“Oh yes, he fabricated the entire journey by car around Transylvania,” O’Sullivan says, at the November launch of his own book on Fermor, about a section in Between the Woods and the Water. “But he did it so brilliantly; it’s actually the best part of the book.”

A Life Lived

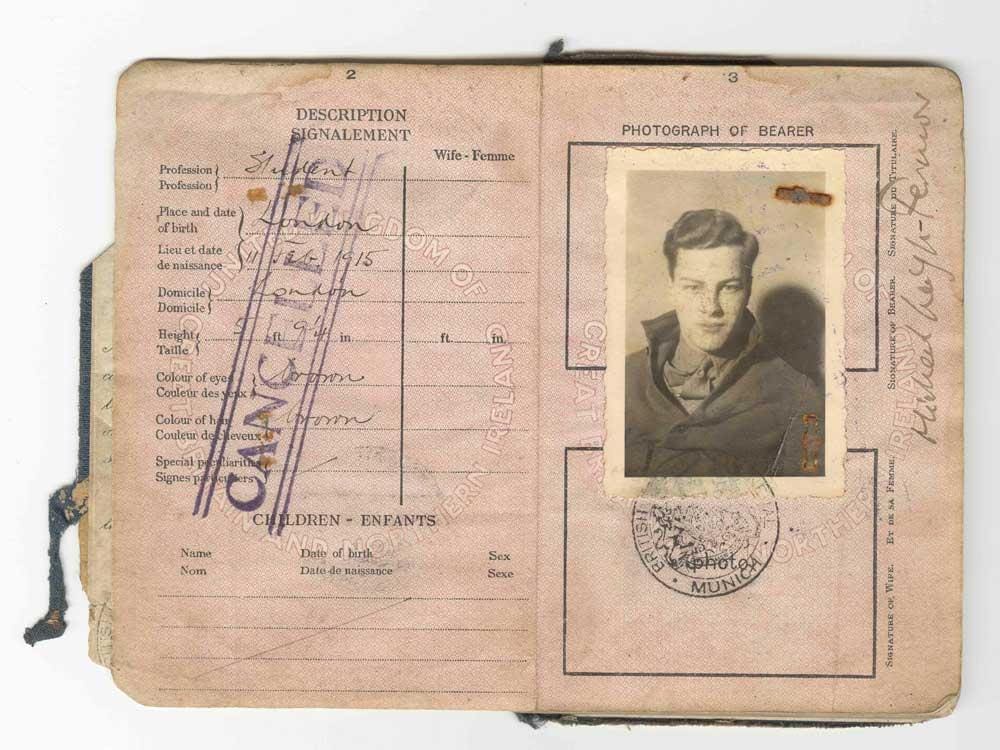

Leigh Fermor – described by the BBC as a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene – is widely viewed as the greatest travel writer of his generation. But despite that lofty title, O’Sullivan describes Leigh Fermor as preferring “to booze than write … he was like Oscar Wilde: putting most of his genius into his rather life than his work”. And what genius it was, as a handful of highlights from his life demonstrate: capturing a Nazi commander and being awarded the Distinguished Service Order (an episode immortalised by Hollywood in Ill Met By Moonlight with Dirk Bogarde playing Leigh Fermor); tangling between the sheets with a Byzantine princess; reading in eight languages; falling foul of a Cretan blood feud; and, in homage to Byron, swimming the Hellespont between Europe and Asia – at the age of 69.

For O’Sullivan, a former foreign correspondent who was introduced to Leigh Fermor’s writings while living in Vienna in the 1980s, it was another extraordinary element of this outsized life that seized his imagination.

“How did an unknown English youth, barely speaking schoolboy French – and farcical German – find his way into the manor houses of the Hungarian nobility?”

It’s this question that O’Sullivan attempts to answer in his book, but his tapestry of meticulously researched mini-biographies offers much more. Lawrence Durrell referred to the ‘truffled style and dense plumage’ of Leigh Fermor’s storytelling. O’Sullivan contributes a historical depth and pathos to the observations of a young man.

This rapt tone surely would have suffered if Leigh Fermor, publishing his trilogy some 50 years after the fact, had retrospectively introduced musings about how his mid-1930s travelogue was, to all intents and purposes, a record of an ancient way of aristocratic life on the brink of annihilation by the onset of World War II and communism.

Treated Like Royalty

To return once again to the matter of the horses. While the inference might be that Leigh Fermor essentially ‘blagged’ his way into the homes of “some of the oldest and grandest families in Europe”, it was actually more of an innocent mistake, at least on his part.

Stopping in Bratislava during his journey, he met an aristocrat, Tibor von Thuróczy, in a bar. It was the letters of introduction that von Thuróczy subsequently sent on that opened up Hungarian high society for Leigh Fermor – except that the noble pedigree to which he had laid claim to von Thuróczy had been a fabrication.

“Leigh Fermor’s mother was a charming old girl,” O’Sullivan says, “but an Olympian-class fantasist.”

The young man had set off under the belief that he was descended from the Tasse family – aristocrats who had travelled from Ireland to Central Europe to become well placed in the upper echelons of the Habsburg Empire (one even became chancellor under Franz Joseph I). With this myth perpetuated by von Thuróczy, the wealthiest addresses of 1930s Budapest were open to him.

“There is much to recommend moving straight from straw to a four-poster,” Leigh Fermor wrote, “and then back again.”

According to letters penned by him in the 1990s, Leigh Fermor seems to have persisted in believing in this noble connection right throughout his life; it’s unknown whether he was in fact deluded or maintaining a façade. But O’Sullivan suggests that while the letters of introduction opened the doors to Leigh Fermor, it was his magnetic personality that allowed him to stay.

The magnetism could, however, be a little too intense. While Leigh Fermor was relatively coy about any romantic conquests in his own writings, O’Sullivan unearthed a number of trysts that the youthful writer engaged in during his epic journey, from literally rolling in the hay with two peasant girls at an estate he was staying at to a love affair with the just married Xenia Csernovits de Mácsa et Kisoroszi – an aristocrat descended from a Serbian family that was ancient – to paraphrase Leigh Fermor – when God was a boy.

O’Sullivan researched the progress of the young woman’s life after the arrival of communism in Hungary. “Xenia was put to work in a Budapest paint factory,” he says. “From living in an extraordinary house, she had to share a flat with a woman who had had the property given to her by the communists. And this woman drove Xenia to such an extent of frenzy that she actually murdered her. But at the trial, all the neighbours went to court and supported Xenia, saying that the woman was so intolerable that she deserved to be murdered.”

O’Sullivan experienced first-hand the dismal results of the deprivations that this class had to endure when he met many of their number in 1980s Vienna. He has described how he shared with Leigh Fermor a fascination for their stories.

“I knew them, liked them and stayed in touch,” writes O’Sullivan. “When the communists fell I returned to Budapest and encountered some of those old families again, living there and trying to regain their heritage,” he now says, describing how, unlike in Romania or Slovakia, there was no restitution of lands or estates in Hungary. Instead, a voucher system was put in place. A friend of told him, “well, we got these vouchers, and we were one of the largest land-owning families in Hungary, and now I can exchange this voucher for a colour television.”

According to O’Sullivan, Leigh Fermor also returned to Budapest throughout his life, doing what he could to help those who had once so generously opened their homes to him.

A Legacy of Gifts

It feels prescient that this book is being published now, with the resurgence of the far right and a nationalist mood on the march. One vignette, about the right-wing Hungarian prime minister who boasted about having the same chest size as Mussolini, seems to carry the same whiff as the overtures made by Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro to Donald Trump. And while the future remains unwritten, Leigh Fermor’s legacy is assured, having inspired travel writers such as Dervla Murphy, Jan Morris and Bruce Chatwin, to name but a few.

But his greatest legacy, according to O’Sullivan, is that he inspires the young. “Young people read this book and they are just riveted by what he did and how he did it.”

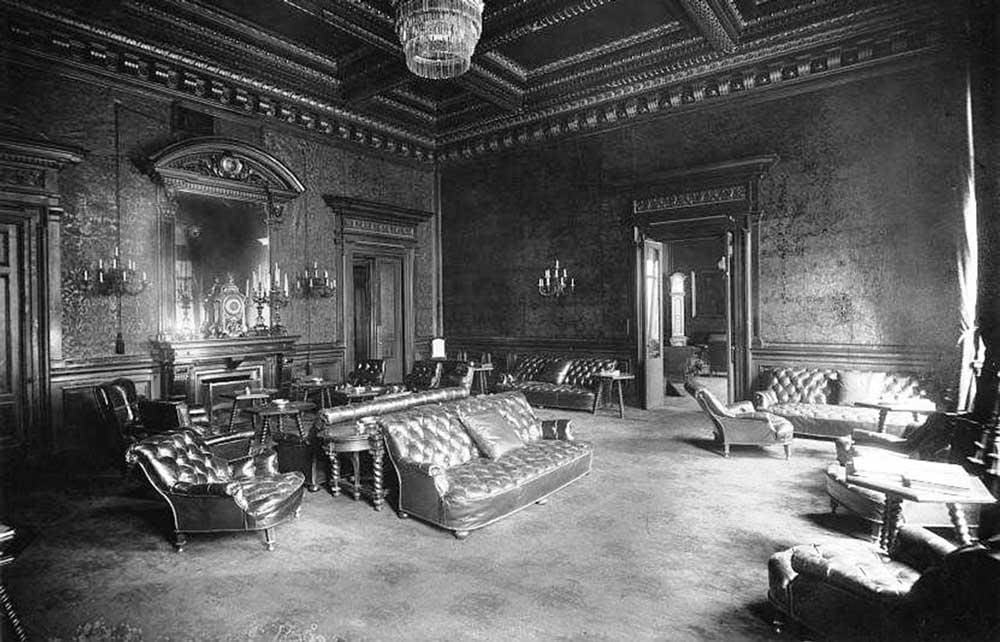

As an example, he points to Katy MacMillan-Scott who (at the time of writing) is engaged in a repeat of Leigh Fermor’s trans-European stroll as a charity walk in memory of a friend. MacMillan-Scott will actually stay in Leigh Fermor’s bedroom, hosted by Baroness Gloria von Berg – a descendant of an aristocrat with whom Leigh Fermor lodged when he first arrived in Budapest. Despite the house having been divided into flats by the communists, von Berg has managed, piece by piece, to buy nearly the entire house back.

O’Sullivan writes of the room: ‘The chair, embroidered with a blue rampant lion with a forked tail and a scarlet tongue, on which Leigh Fermor’s borrowed dinner jacket was strewn, survived the ravages of war, German, Soviet and local plundering during Communist times, but little else remains of the original interior furnishings.’

Not that this should bother MacMillan-Scott. She’ll only need to delve into her undoubtedly well-thumbed copy of Between the Woods and the Water to have it all brought back to joyous, ineradicable life.