British Sparkling Wine: Raising a Glass to Home-Grown Fizz

As French champagne house Taittinger plants vines in Kent, we toast a new era of English sparkling wine

The wind pulled at his greying hair, the rain-speckled his green suit, but the inclement weather couldn’t erase the infectious grin of Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger – president of the eponymous champagne house – as he planted vines at the ceremonial launch of Domaine Evremond vineyard.

This was Kent in the spring, after all. The plantings on 4 May 2017 were the physical realisation of what had been widely known for a number of years – that major players in the French wine market were investing in England’s increasingly vine-crossed Southeast. That Taittinger was the first to take the plunge comes as no surprise; the forward-thinking champagne house also dived into the US market 30 years ago, when it planted vines in Napa Valley under its Domaine Carneros brand.

But what had prompted the French to finally act? Was it the wine world equivalent of a slap with a velvet glove in 2015, when English sparkling wines, in a blind tasting, bested bubbly behemoths such as Pol Roger, Veuve Clicquot, and, indeed, Taittinger? And then – slap, slap – English wine came top at another blind tasting in early 2016.

“Gerard Basset [Master of Wine and Master Sommelier] said recently that England is a bit like New Zealand in the 1980s,” Charlie Holland, winemaker and chief executive of the award-winning Gusbourne winery, tells me. “People are now seeing similarities between New Zealand just before its boom and English wines.”

Following decades of promise, England’s is a market come of age. Technically it could be called English wine’s ‘Second Age’, as the monasteries of the Middle Ages enjoyed flourishing vineyards during a period of global warming referred to as the ‘medieval warm period’. However, the first recorded commercial production of bottle-fermented sparkling wine (the same process used in champagne production) made from, crucially, UK-grown grapes, was in the late 1960s at Pilton Manor in Somerset.

While the Southwest still has its own share of wine producers – most notably Camel Valley in Cornwall – it’s in the Southeast – in Hampshire, Sussex and Kent – that you’ll find the greatest concentration of the 133 and counting commercial vineyards in Britain. And sparkling wine accounts for approximately 66 per cent of their output.

“England is perfectly suited to the production of sparkling, particularly across the South Downs in Hampshire where the chalky subsoil is the same as that found in the Côte des Blancs in Champagne,” explains Ian Kellett, managing director of South Downs-based Hambledon Vineyard which planted its first vines in 1952. “Our climate is also very good. Although average temperatures in July and August are generally lower than in Champagne, we tend to have warmer and longer autumns, which allow the grapes to fully ripen, while preserving acidity levels.”

In fact, as Holland points out, global warming, in part, has created climactic conditions in southern England that match those of the Champagne region in the 1970s. “Thirty years ago, it was difficult to ripen every year,” he adds, “but now we have perfect conditions. We don’t want it to get any warmer, really.”

Global warming, in part, has created climactic conditions in southern England that match those of the Champagne region in the 1970s

As Frazer Thompson, chief executive of Kent-based Chapel Down Winery, observed to The Atlantic, with every degree centigrade that the global temperature rises, the wine growing region moves 270km north. This means that as England reaps the rewards, the Champagne region is pouring huge resources into research to learn how to adjust to the dropping acidity levels caused by warmer temperatures (or, alternatively, just chasing the wine-growing envelope north).

Not that English sparkling is going to dethrone champagne any time soon (production in the UK stands at a diminutive annual average of around five million bottles compared to Champagne’s roughly 300 million), although Brexit could make it more expensive to bring European wine into the country, offering greater incentives to buy local. But while the arrival of Taittinger does, to an extent, “validate English wine”, as Holland puts it, English winemakers are at pains to avoid comparisons with their greatest competitor. It’s a sign of maturity, that awareness that English wine is moving out of the shadow of big names on the world stage.

And while the weather can still deliver a shock, as seen in early May when a late frost (which some called the worst in 27 years) caused catastrophic damage to vineyards across the country, even this can’t knock the confidence of an industry hitting its stride. In fact, producers may even have solved that most vexing question of a unifying brand name for English sparkling à la champagne, cava, or prosecco. Previous suggestions have included the distinctly French-sounding ‘Britagne’ (pronounced ‘Britannia’), as well as the underwhelming ‘Merret’, for English scientist Dr Christopher Merret who helped invent champagne in the 17th century. Instead, it seems that ‘British fizz’, the brainchild of a New York bar owner, has been seized upon. It’s no ‘champagne’, certainly, but, then, isn’t that sort of the point.

Three to Try

Gusbourne Rosé 2013

Gusbourne Rosé – made entirely from Pinot Noir – offers strawberry aromas and a delicate, creamy redcurrant and ripe green apple palate, with a long, dry finish. Established in 2004, Gusbourne owns around 100 hectares spread across Kent and Sussex.

£40, www.gusbourne.com

Hambledon Classic Cuvée

England’s oldest commercial vineyard supplied one of the wines that knocked the French off their sparkling perch in 2015. Hambledon’s blend of Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir produces floral aromas and a vivid palate of greengage and apple.

£28.50, www.hambledonvineyard.co.uk

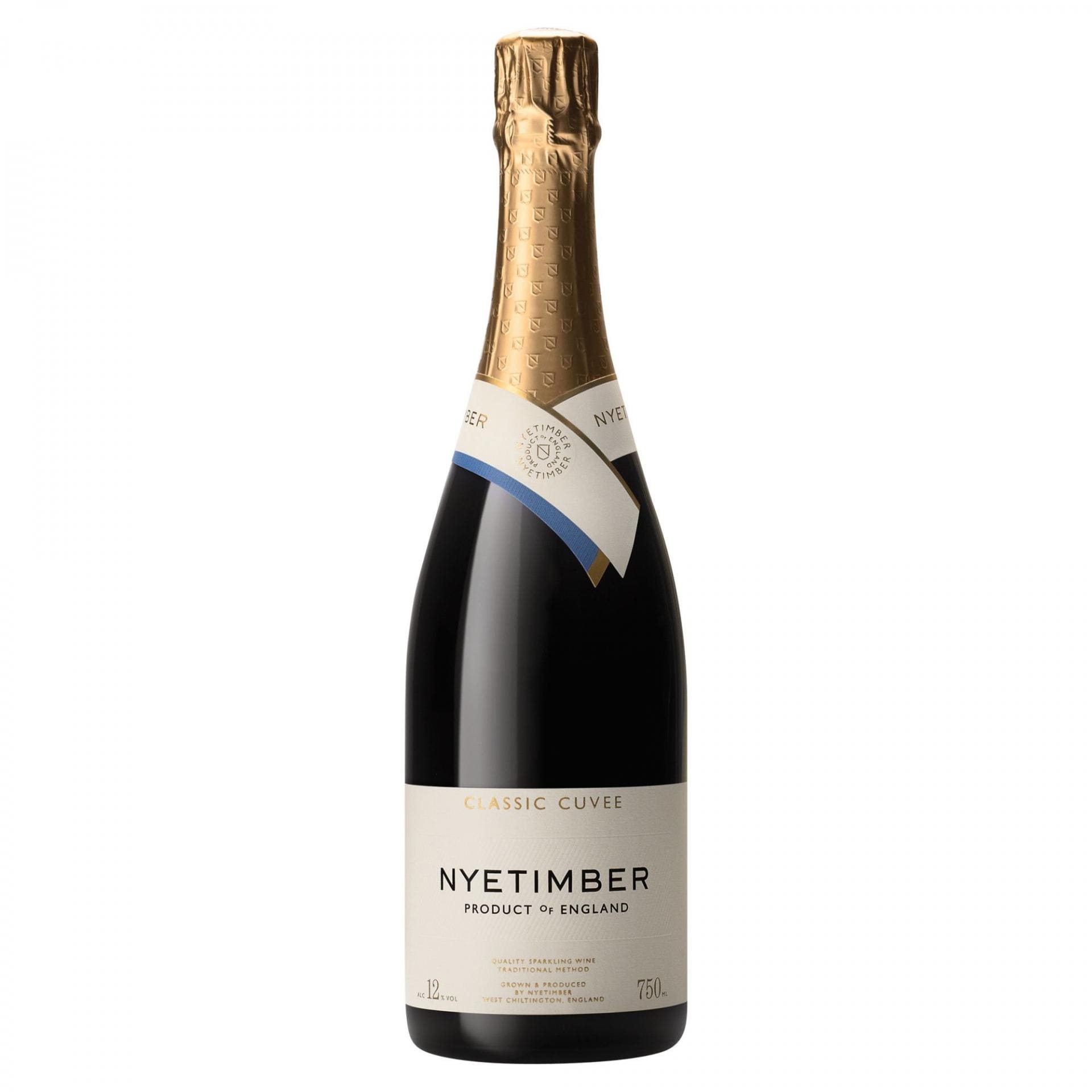

Nyetimber Classic Cuvée

Multi-vintage Nyetimber Classic Cuvée is a pale gold glassful of spice and toast aromas followed by flavours of almond and honey. In 2015, it was the second of the English wines (alongside Hambledon) that won out against the French. Nyetimber – England’s largest vine-growing estate – is respected as one of the country’s leading producers of sparkling wine with 170 hectares across West Sussex and Hampshire.

£34.99, www.waitrose.com