The cult of the Sloane Ranger

For a while, Sloane Rangers seemed to have the life it was only sensible to want. But aspiration only took you so far – you could access the right look, but you’d have to put on the right

“Visitors to London wishing to study the breed should simply take a walk through SW3, 5, 7 and 10 districts, known to the general public as Knightsbridge, South Kensington and Chelsea, where you will find them thick on the ground, in their natural habitat,” suggested The New York Times back in 1984. “They congregate there because they feel safest among their own kind. [Indeed] this sociological exploration is best done during the week. On Friday evenings, the tribe emigrates to spend the weekend in the country houses of friends and relatives.”

Just what was this tribe that fascinated a newspaper of record in a country 5,000 miles away? Princess Diana – back when she was just Lady Diana Spencer – would have known, but then she was their supreme leader.

Indeed, it was the soon-to-be-Princess entering the national consciousness that put the tribe on the sociological map. The tribe in question was the Sloane Ranger, which was suddenly easy to spot around west London (they never went North, South and definitely not East).

Diana was the perfect conduit for the Sloane Ranger: stylish without being radically so; attractive without being (whatever some reckon) traffic-stoppingly beautiful; not exactly a big brain, as befitted a very old-school, upscale way of thinking that contrasted femininity and intellectualism; a Duran Duran fan with a knock-out, butter-wouldn’t-melt sideways glance. She embodied not just the fairytale of marrying a Prince, but the specifically Sloane romantic notion of fulfilling manifest destiny by marrying within the club. All easy chic, champagne, polo games and feathered hair. She looked the part, up and down King’s Road.

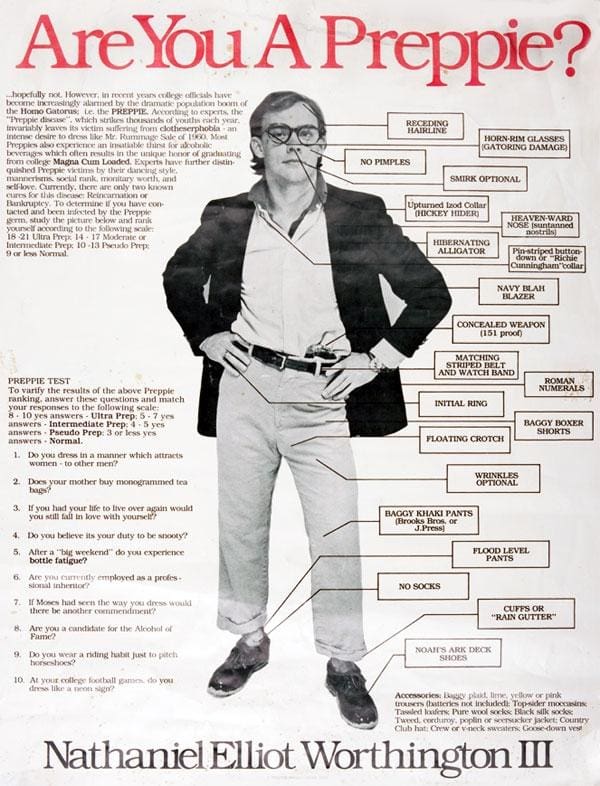

But arguably the genesis of the Sloane was not in Peter Jones but in the US. Forty years ago saw the publication of The Official Preppy Handbook, a tongue-in-cheek study of the styles and mores of those scions of Ivy League colleges, the WASPs – white anglo-saxon protestants – who populated Martha’s Vineyard in the summer, and the East Coast’s more salubrious homes and businesses the rest of the year.

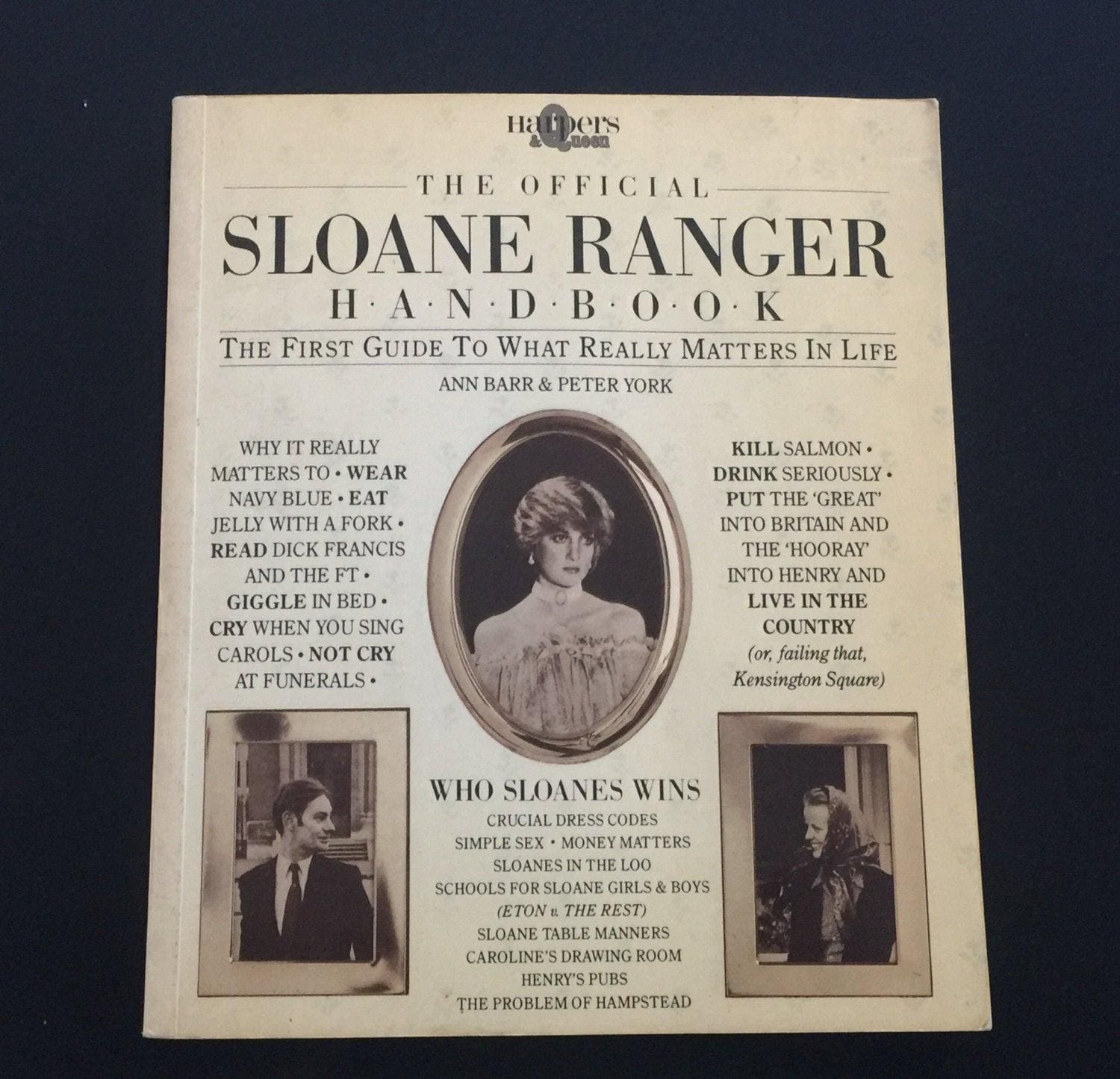

Transpose Martha’s Vineyard for the Cotswolds, or somewhere in Surrey, and the archetypal Sloane was very much a British incarnation of the prepster, as Ann Barr and Peter York hinted at in the title of their defining book, published soon after: The Official Sloane Ranger Handbook. Barr, an editor at Sloane bible Harpers & Queen, York, an astute observer of social groups and behaviours, had long been prodding at the lifestyles of this type of west London native, a portion of society that in 1975 they’d first dubbed the Sloane – a type no doubt rather close to home.

These were the upper-middle-class Londoners who populated Chelsea, hence the moniker, after Sloane Square. They came from comfortable if not aristocratic backgrounds; privately educated, and at the right schools and, as York has noted, “there would need to be, by implication, a bit of toff or posh”.

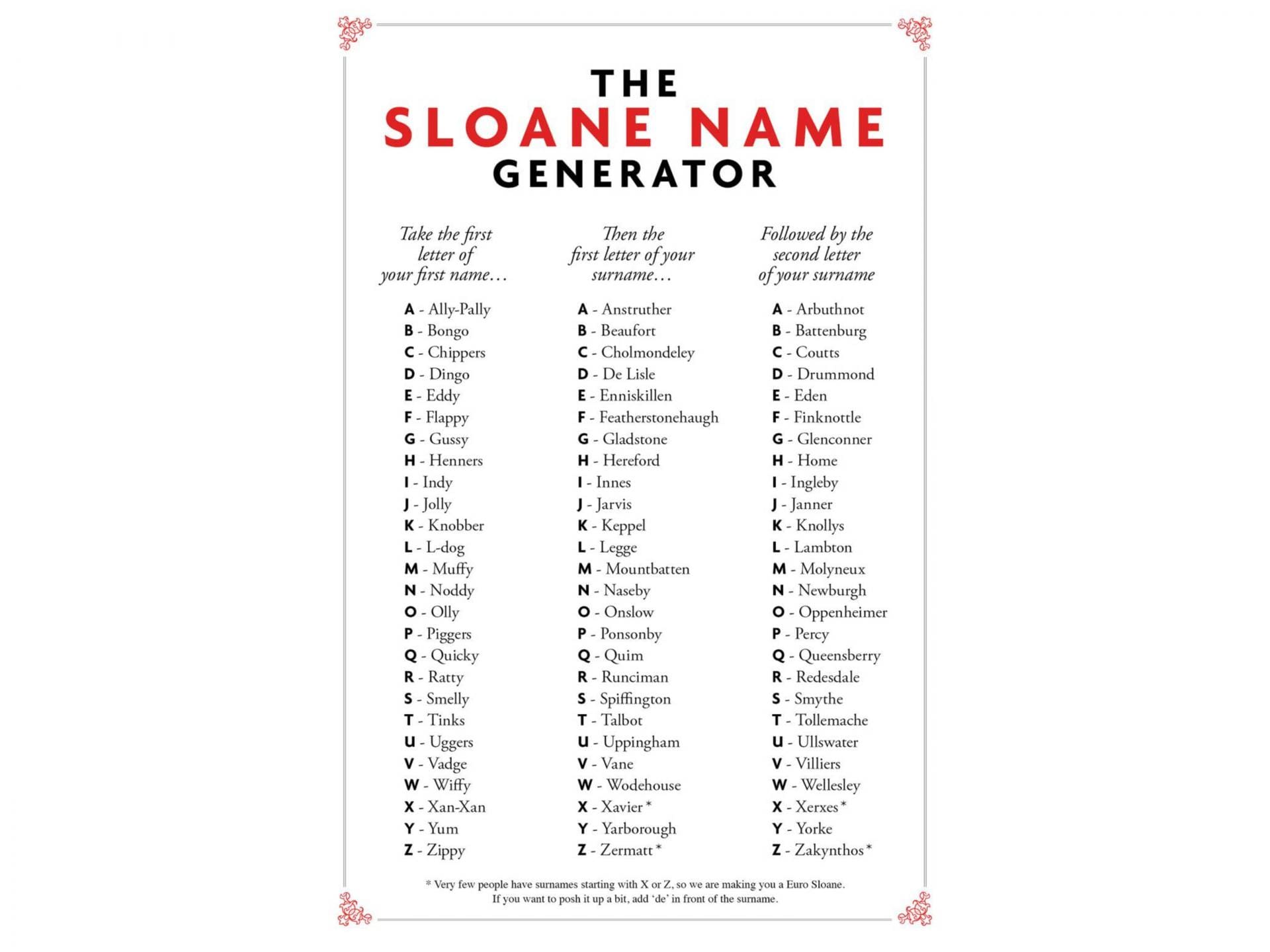

These Sloanes wore the preppyish uniform of their kind: blazers, rugby shirts, gilets, cords in eye-watering colours, brogues, loud socks, pink and pale-yellow shirts with just the right amount of foxing of the collars, a signet ring with a crest on it, worn on the pinkie. It’s a mode of dress that lives on, even at a time when men are much more menswear-savvy. They had predictable, safely middle-class names, too: Toby, Oliver, Ben, Henry, Rupert – when, that was, they weren’t answering to their private school-ascribed nicknames: Piggers, Tinks, Wiffy or Zippy.

For the girls: Josephine, Caroline, Tara or Jemima wore a Hermes scarf, some Gucci loafers or kitten heels, a pleated skirt or matronly floral dress, pie-crust blouse, pearl necklace and a velvet padded Alice band. All such traits were easily emulated by outsiders, of course, and they were: for a while, Sloane Rangers seemed to have the life it was only sensible to want. But aspiration only took you so far – you could access the right look, but you’d have to put on the right accent.

“When Diana Spencer began to appear in newspapers in the summer of 1980, Sloane Ranger style started to gallop down to the high streets,” York has noted. “Suddenly, a Sloane – as we saw her – was the most interesting and publicised person in the world.” And one, perhaps, ripe for gentle pastiche.

The character may have been created a decade later – which speaks to the longevity and resonance of the Sloane – but it was Harry Enfield and cartoonist Nick Newman’s Tim Nice-But-Dim character that finally nailed it. Toothsome, affable but rather limited in outlook, privileged, not work shy but not exactly short of a leg up either, set to be wedded to Lady Sophie Dim-But-Royal. “May you live in bliss,” says, in one sketch, an interviewer regarding the happy occasion. “No, in Fulham actually,” replies Tim.

Does the Sloane Ranger still exist today? Downton Abbey, The Crown and even Megxit has led to enduring interest in all things upper class. The always dapper Prince of Wales has even launched his own clothing line. The entertainment industry now has an atypical share of poshos – from James Blunt to Eddie Redmayne – seeing as though coming from the streets used to be the essential calling card for any ‘authentic’ artist. And certainly it’s been argued that Kate Middleton, born the year that The Official Sloane Ranger Handbook was published, has helped revive the type, with Prince Harry doing the same for the men.

Some industries – among them public relations, the charitable sector, wine merchanting, anything that involves brokering goods for the super-rich and boutique businesses funded by the bank of mummy and daddy – remain dominated by double-barrelled names. That, though, is possibly just a product of needing to come from money to make headway in an effervescently expensive capital. Meanwhile, social inequality has become a hot topic. Class remains a curiously British obsession.

In 2007, York’s inevitable, fun follow-up, Cooler, Faster, More Expensive: The Return of the Sloane Ranger, proposed that the tribe had split into new factions, among them the Eco Sloane, the extravagant Turbo Sloane, even – such a horrible, dated term – the Chav Sloane. But others, too, have spoken of the Millennial Sloane, less demure than the original variety, defined less by their breeding as their bank balance, the products less of families with extensive family trees as those founded on celebrity. They’re still conservative, still rather middle-brown, still rather middle-aged before their time. As the Handbook puts it, Sloanes are “a living museum of old modes of behaviour”, only this time their parents are aging models, actors or rock stars.

Yet surely few now would embrace the description, as they might have 40 years ago. Then ‘Sloane Ranger’ may have been used affectionately, latterly more derisively. Perhaps the Sloane has become more a figure of fun than one of aspiration. After all, even they have been priced out of the heart of west London, pushed all the way to Earl’s Court, less able to congregate in sufficient numbers to define an area. Sloanes were squeezed out – geographically but also culturally – by the holders of brash, new, huge money who came in, gobbled up all the Sloane institutions and imposed some meritocracy. In 1989, the Sunday Times Rich List noted that two-thirds of the wealth of those on its register was inherited; by 2000, three-quarters of it was self-made.

And then, as York has explained, Sloanes became something of a “walking joke”, taking the bold adventure of shifting their social lives to the stranger, more progressive – for being that much poorer – lands of the East End and putting on mockney accents in order to hide their true identities: Sloane Ranger disguised as Hipster. If Sloanes had long been resistant to seeing themselves as such, crucially, so well-established did the stereotype become that it was finally acknowledged as faintly comical even by those who most embodied it – those silly nicknames were suggested by the ‘Sloane Name Generator’, published in 2015 by, of all publications, Tatler.

It was that Sloane-friendly magazine that proposed it was still possible to spot a Sloane if you looked hard enough. But it suggested a less positive series of identifying characteristics: bad posture; a blend of confidence and deep emotional insecurity, constrained by the conventions they’ve inherited; boozy; predictable; unable to look beyond their own tribe for either friendship or love. It’s not a pretty picture, and inevitably it prompts a little schadenfreude. Maybe Sloane Rangerdom, then, is better just remembered as a moment in style, not as some way of being that continues to define pockets of west London.