The Legacy of London Calling: Why The Punk Album is Still Relevant Today

Forty years after its release, London Calling, the classic post-punk album by The Clash, remains one of the greatest records ever inspired by the capital – and as fresh as ever

A lot can happen in 65 minutes. From the moment the needle (and you really should be playing this record on the format for which it was originally made) hits the grooves on London Calling to the moment when, just over an hour later, the album ends, seeming to almost leave smouldering ash on the turntable, we witness the death of a gambler in an opium den (‘seized and forced to his knees and shot dead’); get lost in a supermarket where special offers of ‘guaranteed personality’ are in short supply; meet Ivan from Brixton, and ask whether he’ll come with his hands on his head or on the trigger of a gun when the law comes calling. We travel to civil-war ravaged 1930s Spain to find ‘bullet holes in the cemetery walls’ and ‘the black cars of the Guardia Civil’. And we find escape, too; chiefly in a brand new Cadillac whose young female owner has a few choice words to say to her father: ‘balls to you Daddy’ and ‘I ain’t never coming back’.

We haven’t seen much of that fiery protagonist since she sped off into the night on just the second track of London Calling. But the album itself has stuck around for four decades and counting, regularly featuring in lists of Best Ever Albums, sneering and snarling at everything ranked around it. This is an album named after London and loosely based around the city. And, just like the city itself, there’s nothing myopic or parochial about this record, not least in terms of its scope of ambition.

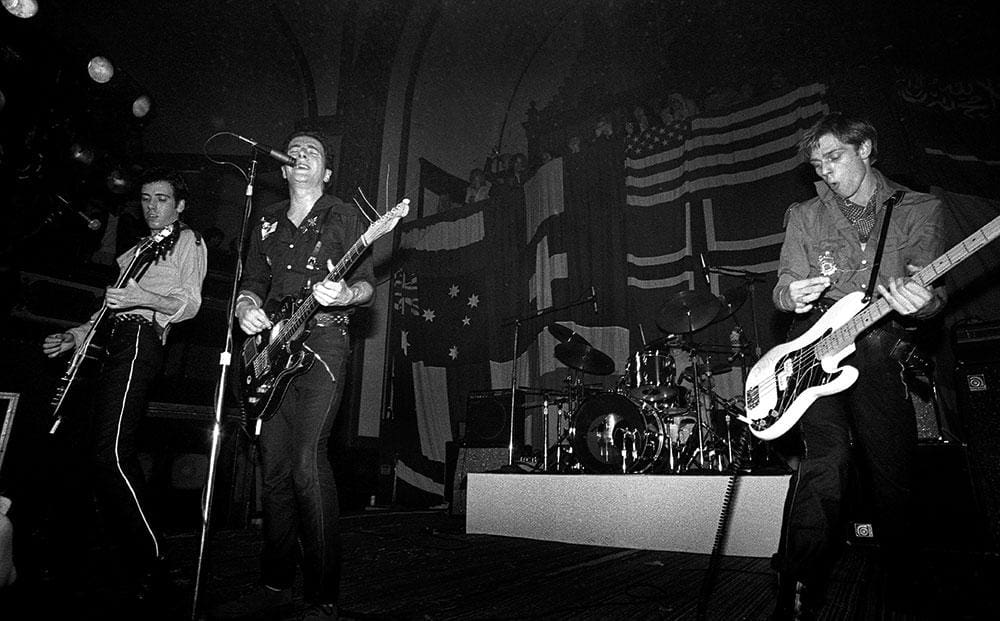

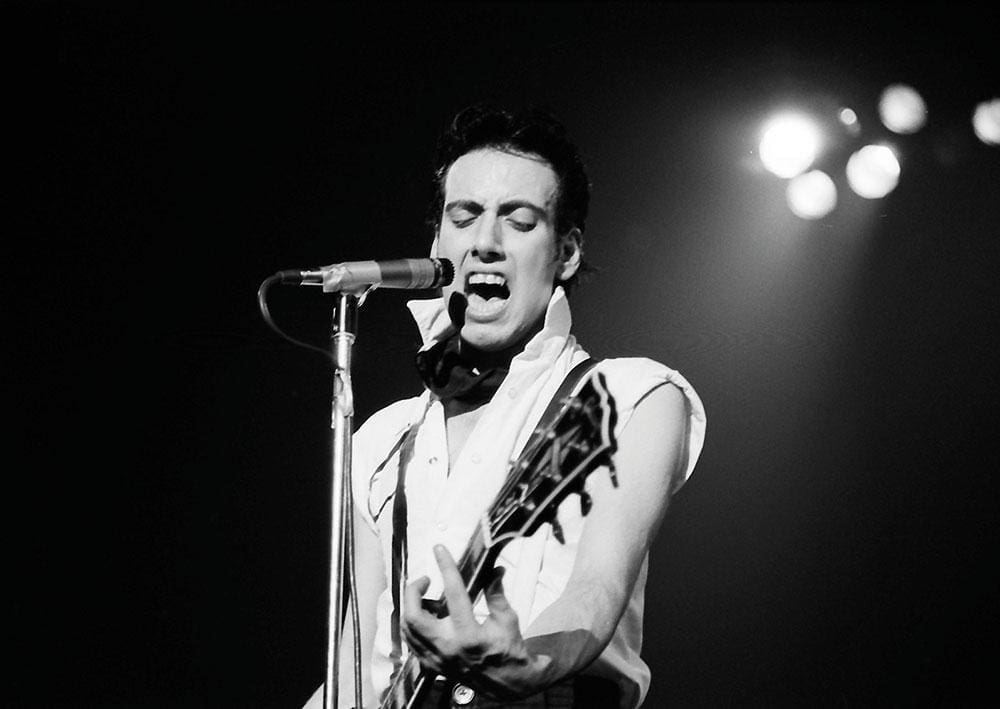

‘When I play [my guitar], you’re hearing my life come out in microcosm,” said Mick Jones, who, along with singer Joe Strummer, bassist Paul Simonon and drummer ‘Topper’ Headon had already ridden the first, chaotic, choppy waves of the Big Bang of the punk rock scene that erupted into being during 1976. The Clash supported the Sex Pistols on their debut tour, though the vast majority of gigs were cancelled by venues and local councils who considered punk rock to be something akin to the arrival of the devil on horseback. Even today the band remains somewhat in the shadow of Johnny Rotten, Sid Vicious and co, considered too serious and ambitious compared to the supposed authenticity of the Pistols.

London Calling, the band’s third album, was released in the last month of the 1970s. The Pistols had imploded, Vicious having died of a heroin overdose, and the initial wave of punk bands had been exposed as predominantly egotistical chancers who couldn’t sustain their initial, amphetamine-fuelled success. Here then, was something very different. This double album (sold for the price of a single one) showed The Clash as a band with a depth of intelligence, style and raw, red-eyed, vapour-trailed soul that dwarfed the movement from which they originated.

The title track was a dire forewarning of the decade to come. Speaking of a ‘nuclear error’, a new ice age, the flooding of the capital city and the sun’s end, London Calling spoke of no less than the imminent destruction of the city and the fields and oceans surrounding it. “In the 70s, when we formed the band, there was a lot of tension in Britain, lots of strikes, and the country was an economic mess,” commented Simonon in a 2013 interview. “There also was aggression toward anyone who looked different, especially the punks. So the name The Clash seemed appropriate for the band’s name.”

The 1978-1979 Winter of Discontent saw rubbish piled 20 ft high in Leicester Square and grave diggers on strike; the December 1979 timing of the album’s release further reflected the anger, anxiety and trauma of the final throes of the decade. The band knew it. The LP was sold with a sticker which proclaimed The Clash as being ‘the only band that matters’. Although the recording process itself would test the mettle of even these hardened, committed rock ‘n’ rollers to breaking point.

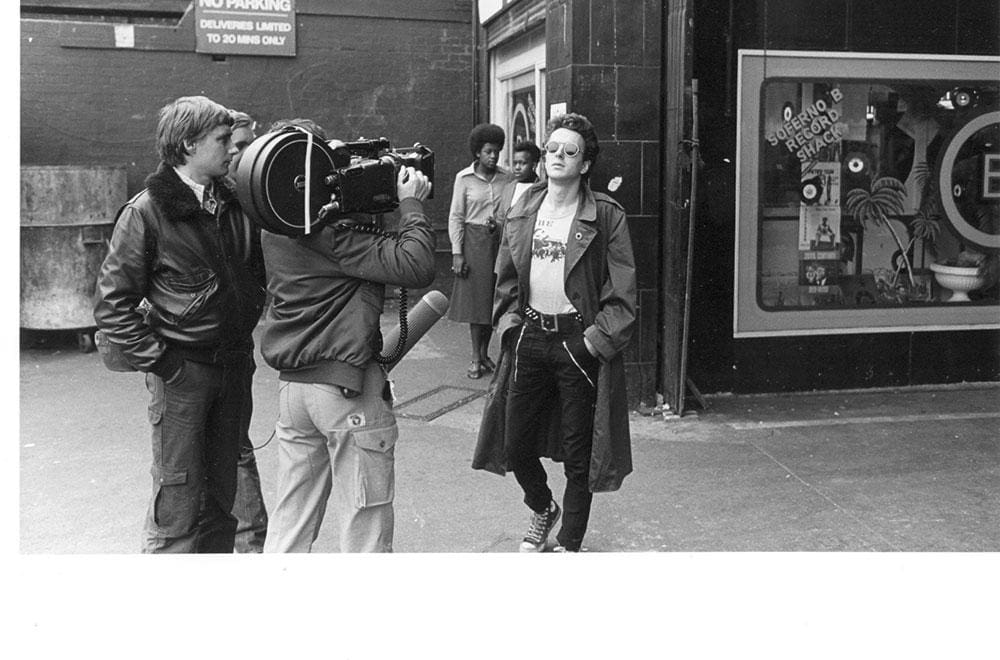

Producer Guy Stevens’ reputation was forged from his work with early 70s rock acts such as Free and Mott the Hoople. Stevens, however, was a chronic alcoholic and by the end of the decade, he had swapped the studio for the pub. Strummer, undeterred, set out to find him, working his way through the pubs situated off Oxford Street that Stevens was known to frequent. “I went up to him and tapped him on the shoulder,” Strummer recalled in an NME interview at the time of the album’s release. “He looked around and it was like a son finding his father in one of those corny old films. He looked up at me and said ‘Have a drink’.”

During 18-hour recording sessions over a period of around six weeks, Stevens spent much of his time producing London Calling by pouring wine into pianos while Strummer was recording, smashing up chairs in front of representatives of CBS records, sleeping under the console and swinging ladders around the studio. This frenzied havoc was reflected in the wildly disparate range of styles heard on the album, which lurch and swagger around reggae, old-school R&B, jazz, rockabilly, ska, pop, soul and rock.

Critical acclaim and huge sales were instantaneous upon the album’s release. It sold two million copies and critics lined up to pay tribute to its immense breadth and vitality. ‘This is an album that captures all The Clash’s primal energy’, wrote The New York Times, going on to note how ‘a brilliant production job by Guy Stevens… reveals depths of invention and creativity barely suggested by the band’s previous work.” Rolling Stone magazine would later name London Calling the album of the 1980s – it wasn’t released until January 1980 in the United States.

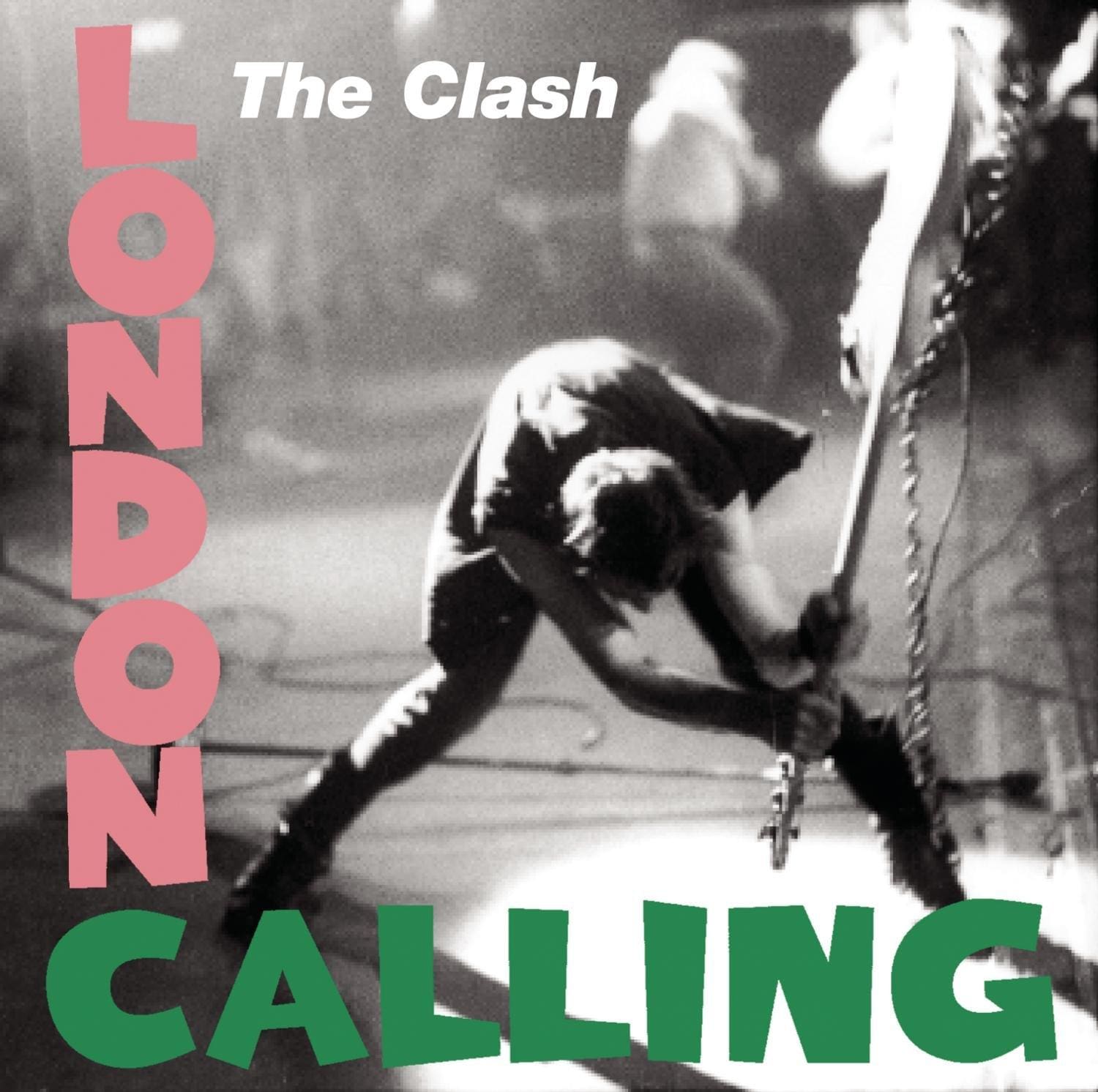

And yet, amid these raw seams opening up on the rock coalface, there was a sense of finality and closure to London Calling. The Clash were being touted at this time as ‘the last great rock band’ and the album itself was originally intended to be called The Last Testament. The sleeve itself suggests a sense of closure on the first era of guitar rock. The vertical and horizontal pink and green lettering on the sleeve is an exact replica of that on the cover of the eponymous debut album by Elvis Presley. While the King of Rock and Roll is joyously holding up a guitar on his 1956 album, on London Calling Simonon is caught flinging a guitar back down towards the floor.

“We didn’t have any solution to the world’s problems,” said Strummer when asked, two decades after its release, about the influence of London Calling. “We were trying to grope in a socialist way towards some future where the world might be less of a miserable place than it is. If Karl Marx was unable to do it then there’s no way four guitarists from London could do it.”

The momentum didn’t last. Their next album, Sandinista!, was a sprawling, two-and-a-half hour long triple album that tested the patience of even the most dogged fans. The subsequent departures of Headon and Jones prompted a catastrophic downturn in the quality of output that reached its nadir with the band’s final album Cut the Crap in 1985.

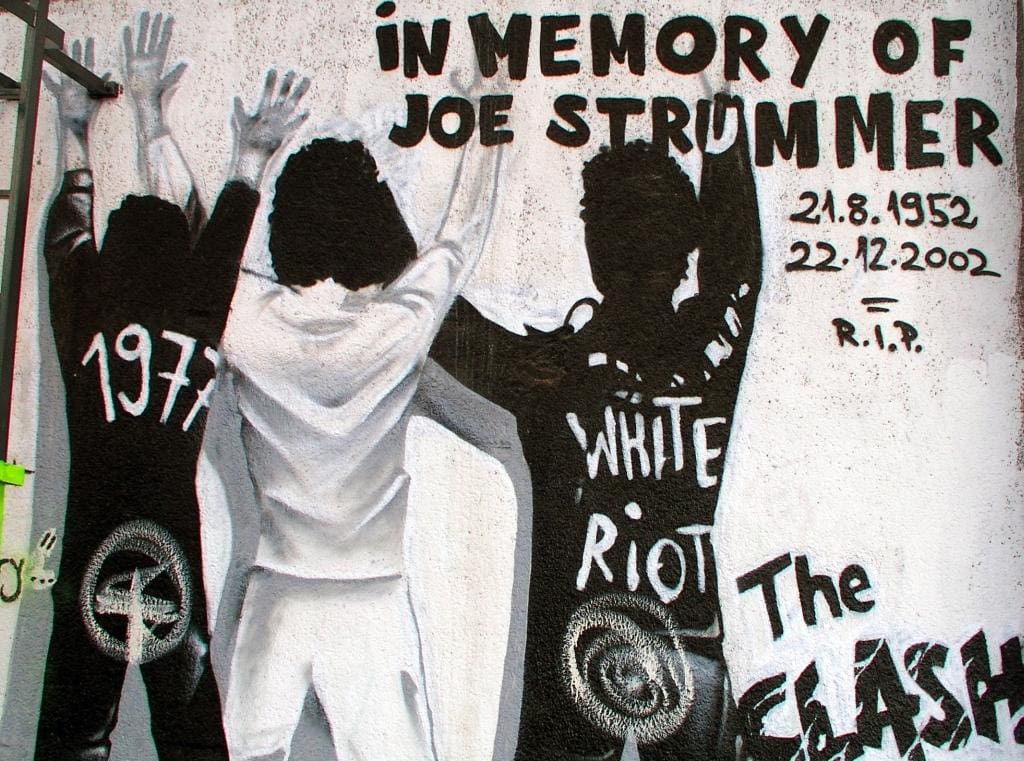

As for Stevens, barely two years after the release of London Calling, he would die of an overdose aged just 38. Strummer himself only lived to be 50, dying of an undiagnosed congenital heart defect in 2002. And yet the sheer youthful exuberance, the abandonment, the thirst for knowledge, the hunger for change, the adoration of the city and, most importantly, the desire for the new and a dismissal of the old, still shine through in 2019. The freshness of London Calling, if anything, only seems to improve, as the issues it addresses remain as ever-present and as seemingly insoluble.

“You have to think to yourself, ‘What would you do if you did rule the world?’” said Strummer in an interview recorded shortly before his death. “It’s a tough question and I don’t think we had an answer to it. Not that we should have done, but we did try to put our minds to pose those kinds of questions. Whatever use that was. But we did try.”