Hear my train a Comin’ – the final days of Jimi Hendrix

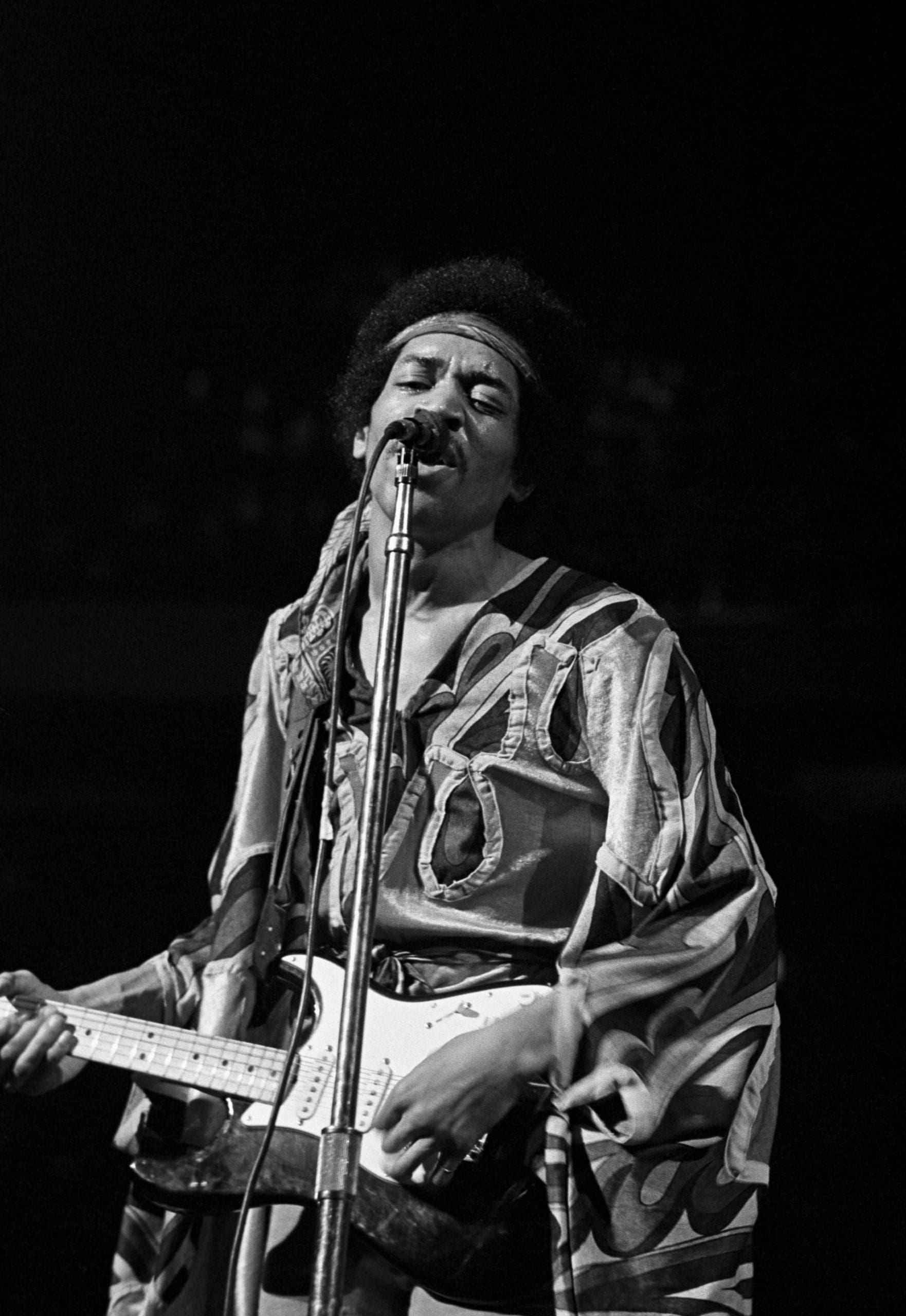

Half a century ago, the world’s greatest guitarist died in tragic circumstances in a small, central London flat. Luxury London looks back on the torrid final days of Jimi Hendrix

‘The story of life is quicker than the wink of an eye. The story of love is hello and goodbye. Until we meet again’.

A few hours after he wrote these lines, the most sublimely gifted musician of his generation was dead in his bed, having choked on his own vomit after a typical evening involving groupies, parties, wine, joints, amphetamines and barbiturates.

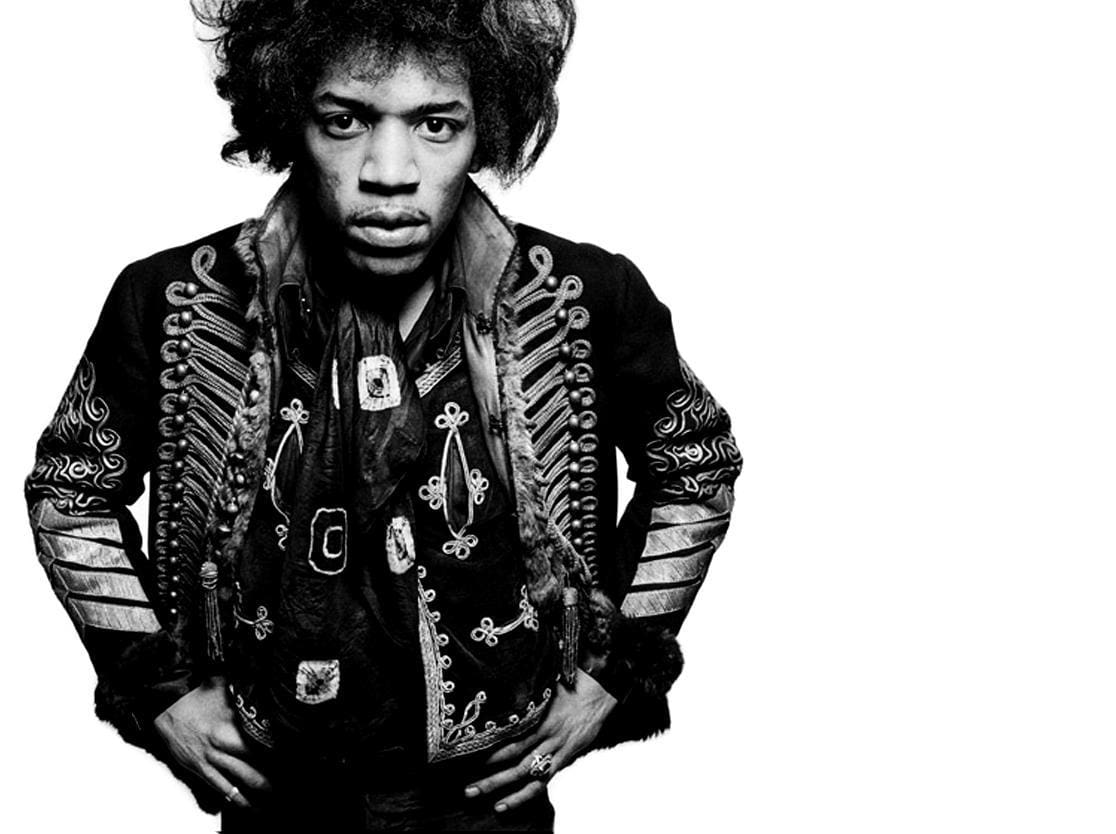

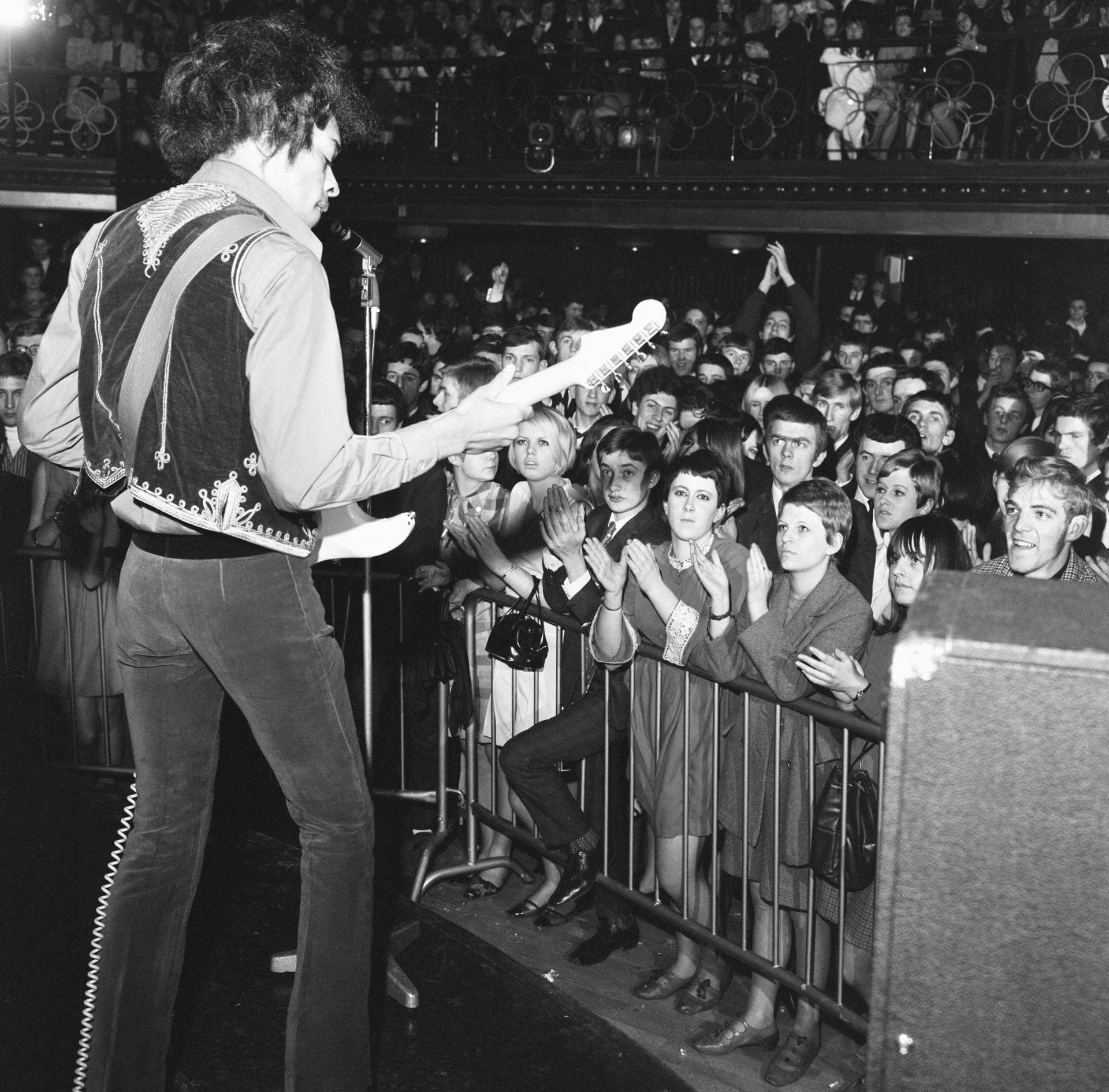

Fifty years on, rumour and inconsistencies still persist around the death of a man who, all but ignored in the United States, found his most fanatical audience in London. For it was this city that embraced Jimi literally from the moment he first stepped off a plane in September 1966.

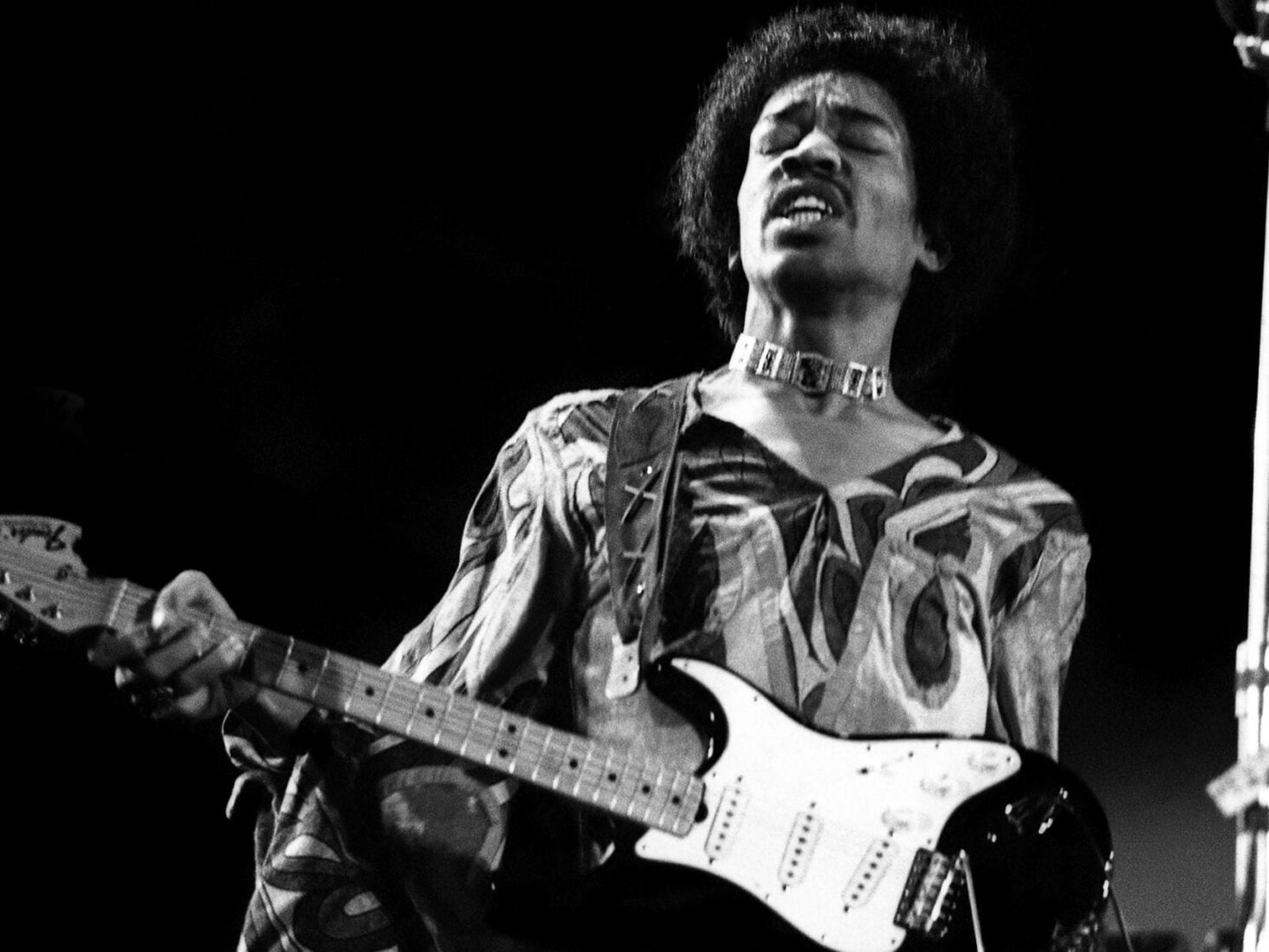

At the time, Hendrix was known only by a few cognoscenti in the Greenwich Village live music scene. The term ‘overnight success’ could be coined to reflect how this transcendently charismatic musician was received when he first arrived in London in 1966. Eric Clapton was among the first to recognise Hendrix’s genius, the Yardbirds and Cream guitarist quick to realise that here was a man whose skill and craftsmanship with the instrument were light years ahead of anyone else on the planet.

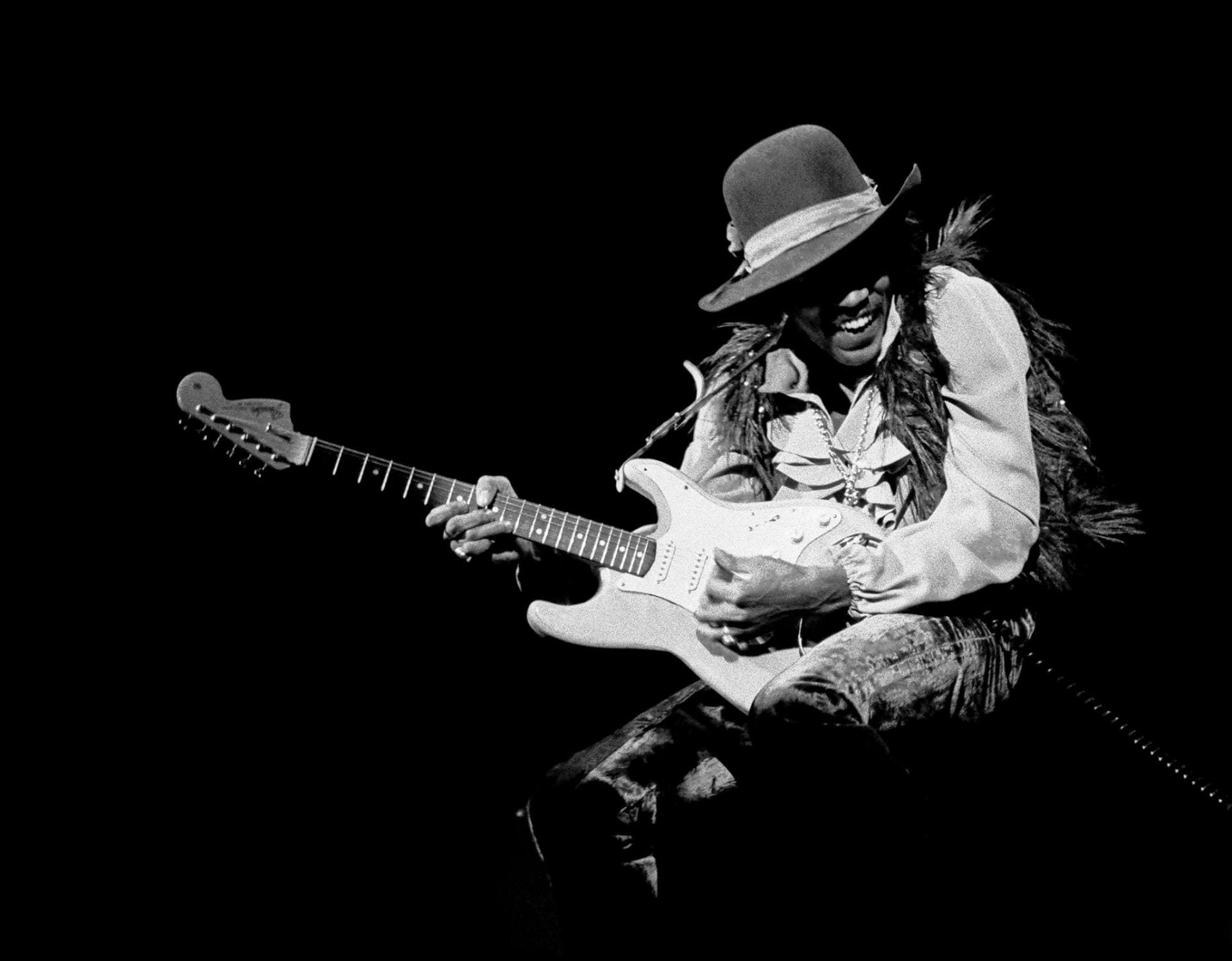

“He played just about every style you could think of, and not in a flashy way,” recalled Clapton. “I mean he did a few of his tricks, like playing with his teeth and behind his back, but it wasn’t in an upstaging sense at all, and that was it … He walked off, and my life was never the same again.”

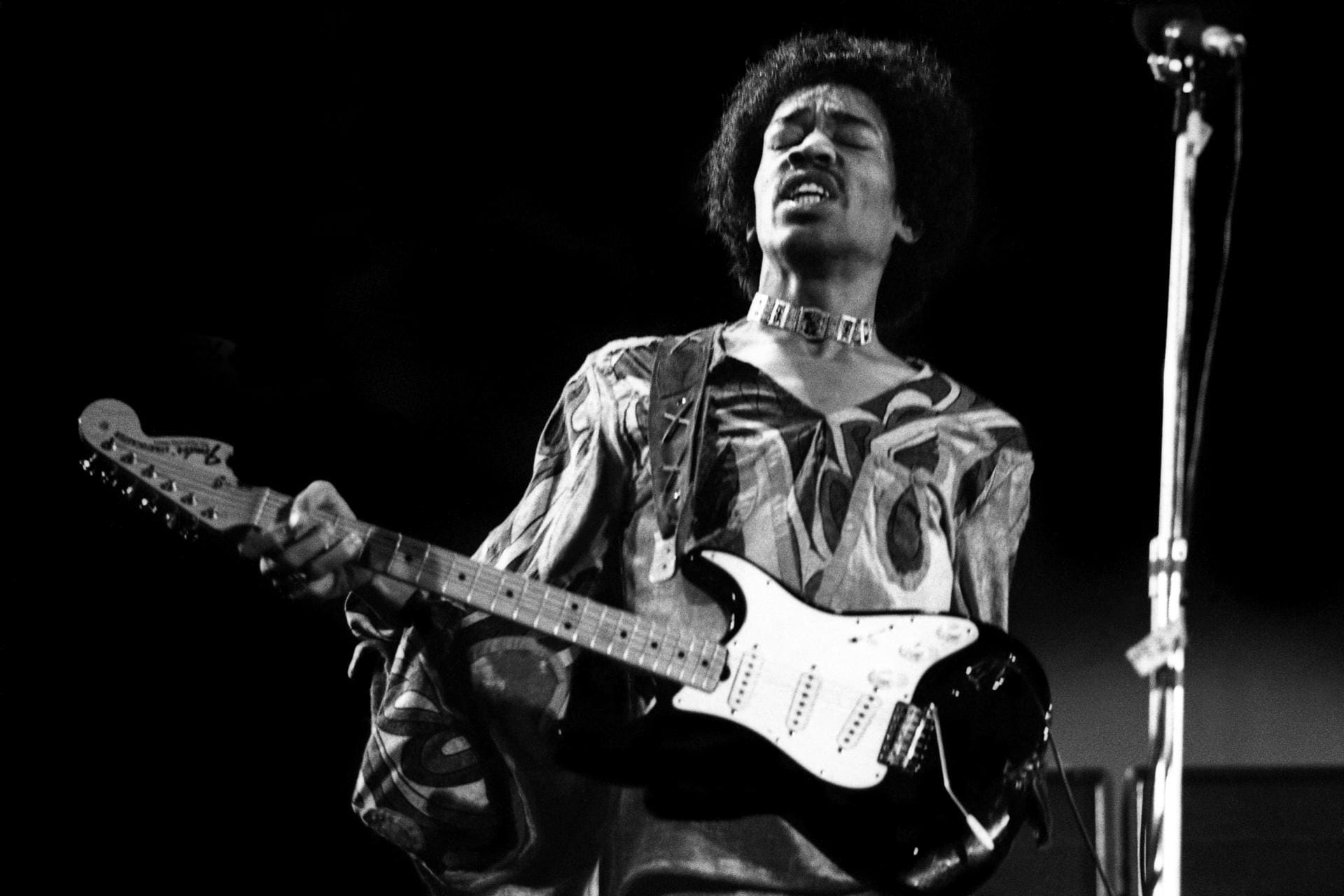

Fast forward a mere four years and Hendrix, still using London as his base, had evolved from being the genius behind chart-friendly rock and blues juggernauts like Hey Joe and Foxy Lady into a musician increasingly shying away from mainstream chart success in favour of more esoteric, jazz-influenced sounds.

Predicting his own early death in 1970 while on location in Hawaii for the shambolic hippy film Rainbow Bridge, Hendrix remarked on set to fellow cast and crew members that if he ever went back to his home city of Seattle it would be ‘in a pine box’.

Wrecked by an ever increasing diet of hard drugs and a relentless touring and recording schedule, Hendrix’s physical and mental health was in tatters, causing him to abandon a gig in January half way through due to having taken bad acid before heading on stage.

An early autumn return to London after a typically chaotic opening to his own Electric Lady Studios in New York should have been the cue for some extensive recuperation, but the temptations of the city were too much for Hendrix to resist.

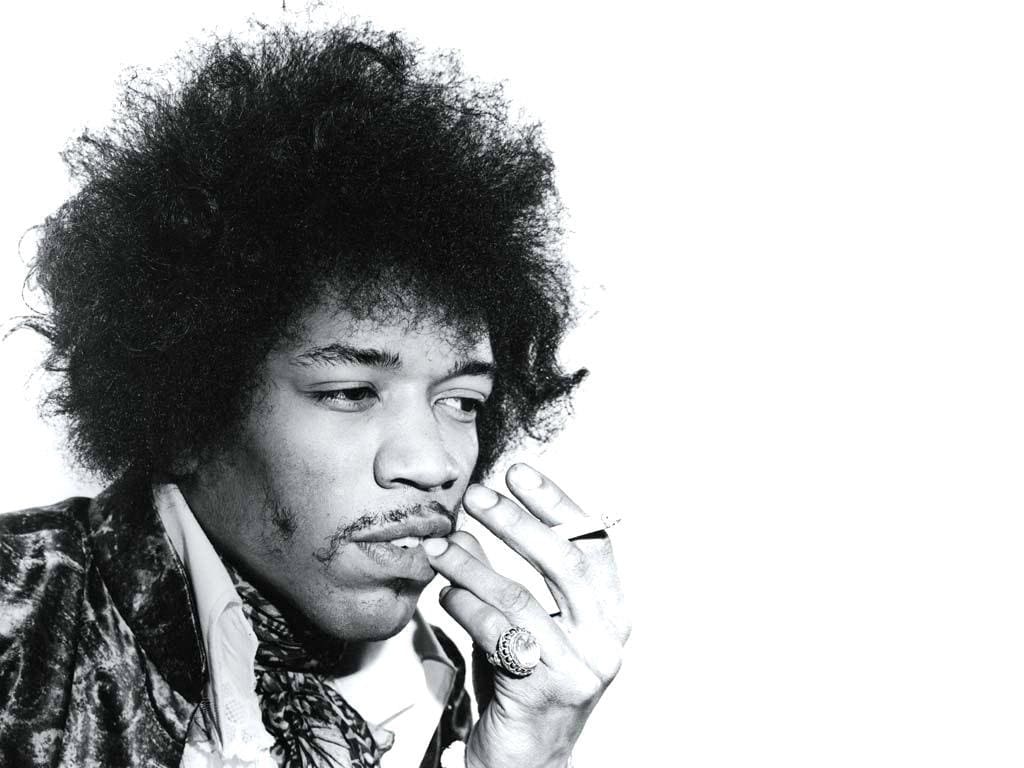

He was dating the German figure skater Monika Dannermamn, and the two of them would take drugs in her flat inside the Samarkand Hotel in Notting Hill. Hendrix was wary of spending too much time in public view; he had two lawsuits pending, one a paternity case, and was under pressure from his manager Mike Jeffrey, as well as his record company, to come up with a new product and new concert dates.

Appearing briefly at a party with Monika after penning The Story of Life at Dannermamn’s flat, a notably depressed Hendrix complained to fellow partygoers about his frustrations with the music industry and with Jeffrey, before returning to the Samarkand with Dannermamn. It was almost dawn when, on top of the wine and amphetamines he’d consumed that evening, he took up to nine sleeping pills along with a tuna fish sandwich, according to Dannermamn.

Dannermamn claimed that she awoke some time between 10am and 10:20am the next morning, and found Hendrix sleeping normally in bed next to her. She said she then left to purchase cigarettes, and when she returned at around 11am found him in bed breathing, although unconscious and unresponsive. By the time the ambulance arrived at St. Mary Abbot’s Hospital, Hendrix’s heartbeat and pulse were already flat.

James Marshall Hendrix was declared dead at 12:45pm on Friday 18 September 1970. He was 27.

The coroner’s open verdict and the lack of any investigation surrounding his death meant Dannermamn’s story went officially unchallenged for more than 20 years.

It was only in the early 1990s that Hendrix’s ex-girlfriend Kathy Etchingham located the ambulance men who attended the scene at the Samarkand Hotel. Reg Jones stated that when they were called to the flat Hendrix was fully dressed and alone, with Dannermamn nowhere to be seen. It was subsequently suggested that Hendrix had already been dead for some hours.

Dannermann died in 1996 and with no surviving witnesses from that morning in September 1970 left alive, rumours still abound. Was Hendrix’s body moved to Dannermamn’s flat after an overdose elsewhere in London? Was he killed on the orders of a cabal of mafia bosses of whom Mike Jeffreys was believed to be involved with? Was he a victim of a J. Edgar Hoover-sponsored programme to kill celebrities who sympathised with the Black Panther movement?

The medical evidence that finally emerged in the 1980’s does suggest the possibility of foul play. Although the official autopsy shows consumption of sleeping tablets as the cause of death, it’s far from definite that these would have been fatal for Hendrix, a chronic insomniac with a high tolerance of barbiturates.

The doctor at the hospital where Hendrix’s death was officially recorded also stated that the large quantities of red wine were present in his throat, stomach and lungs. There was littlealcohol in his bloodstream, suggesting that he could have been held down and drowned by having wine poured down his throat.

Political motivation for the musician’s death is also not as far-fetched as it might ostensibly appear. His disturbing, feedback-spattered performance of The Star Spangled Banner at the 1969 Woodstock festival was still fresh in the memory. Hendrix attracted Black Panther supporters to his concerts and their actions, if not their more overt violence, struck a chord with him, as he remarked. “It isn’t that I’m not relating to the Black Panthers. I naturally feel a part of what they’re doing, in certain respects. Somebody has to make a move, and we’re the ones hurting most as far as peace of mind and living are concerned.”

According to the documentary Jimi Hendrix: The Last 24 Hours (2004), declassified FBI documents show that Hendrix appeared on a list of dissident musicians, writers and artists who would be put into a detainment camp in the United States should the escalating black radicalism and violent opposition to the Vietnam War reach the point of national emergency.

Much of the content of these papers remains redacted to this day. Like the reverb on one of Hendrix’s incendiary guitar solos, the truth continues to flutter and waft into the unknown, remaining beyond reach to those who remain.

Half a century on, his final written words still seem to contain something of that restless spirit, a soul that beguiled London, creating sounds that remain some of the most restlessly inventive of the past century.

‘All the tears we cry. No use in arguing. All the use to the man that moans. When each man falls in battle. His soul it has to roam.’

Electric London-Land – Three Hendrix Hotspots in the Capital

23 Brook Street

The bedroom of the Mayfair flat where Hendrix lived for much of 1968 and 1969 with his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham has now been restored to look almost exactly as it was during Hendrix’ tenure, all the way down to knick-knacks bought on the Portobello Road and furnishings from John Lewis. You can buy tickets to visit the flat (immediately next door to the flat Handel lived in 200 years earlier) at handelhendrix.org.

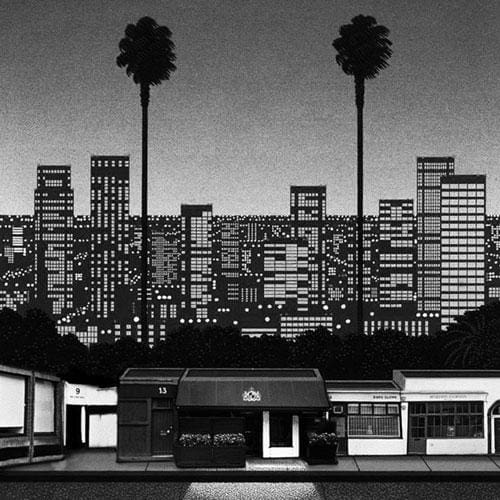

Ronnie Scott’s

It’s a little more open minded in its music policy these days, but Hendrix was never given the most rapturous of welcomes by the famously aloof jazz crowd when he played at this Soho institution. It is, however, the site of his last ever public appearance, he jammed here just two nights before his death.

ronniescotts.co.uk

Scotch of St. James

Reopened after a gap of almost a quarter of a century in 2012, the original incarnation of this bijou West End club was where Paul McCartney first met Stevie Wonder. In 1966, Hendrix, having only arrived from the States earlier that day, sweet-talked his way onto the stage to join the house band and, according to those who were there, blew them off the stage with his version of Wild Thing by The Troggs.

the-scotch.co.uk