70 years of 1984: how London inspired George Orwell’s dystopia

Seventy years after the world was introduced to Room 101, the Thought Police and Big Brother in George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, we revisit the author’s terrifying vision of London as the capital of Airstrip One

Bombed out clearings where citizens live ‘in wooden dwellings like chicken houses’. Grim, filthy canteens where workers are fed morning cups of gin that taste like nitric acid and deliver a ‘sensation of being hit on the back of the head with a rubber club’. Monolithic concrete tower blocks with boarded-up windows, casting shadows over slums, and ‘old bent creatures shuffling along on splayed feet’. This is London. No longer the capital of England but the capital of Airstrip One, part of Oceania, a vast political entity in a state of war that, as George Orwell (the pen name of Eric Arthur Blair) describes, is ‘not meant to be won, it is meant to be continuous’. Of all the dystopian visions of the future that authors, screen writers and even politicians have imagined for London, none come close to Orwell’s in terms of pure, unmitigated horror.

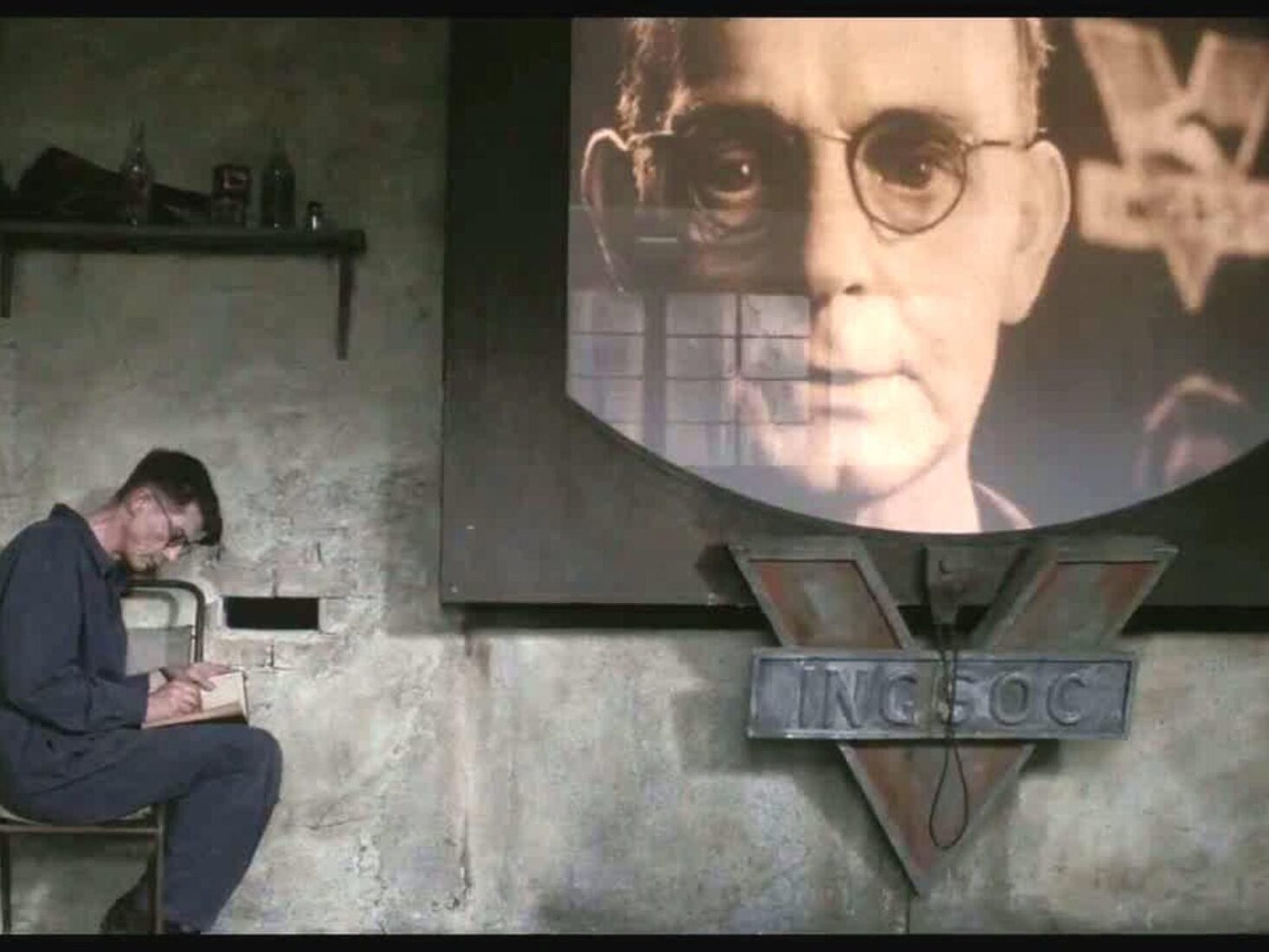

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, published exactly seven decades ago, the chief city of Airstrip One is home to central character Winston Smith, an apparatchik at the Ministry of Truth whose job is to alter back issues of The Times, falsifying history and thus ensuring that the policies of the omnipresent Party and Big Brother can never be disputed.

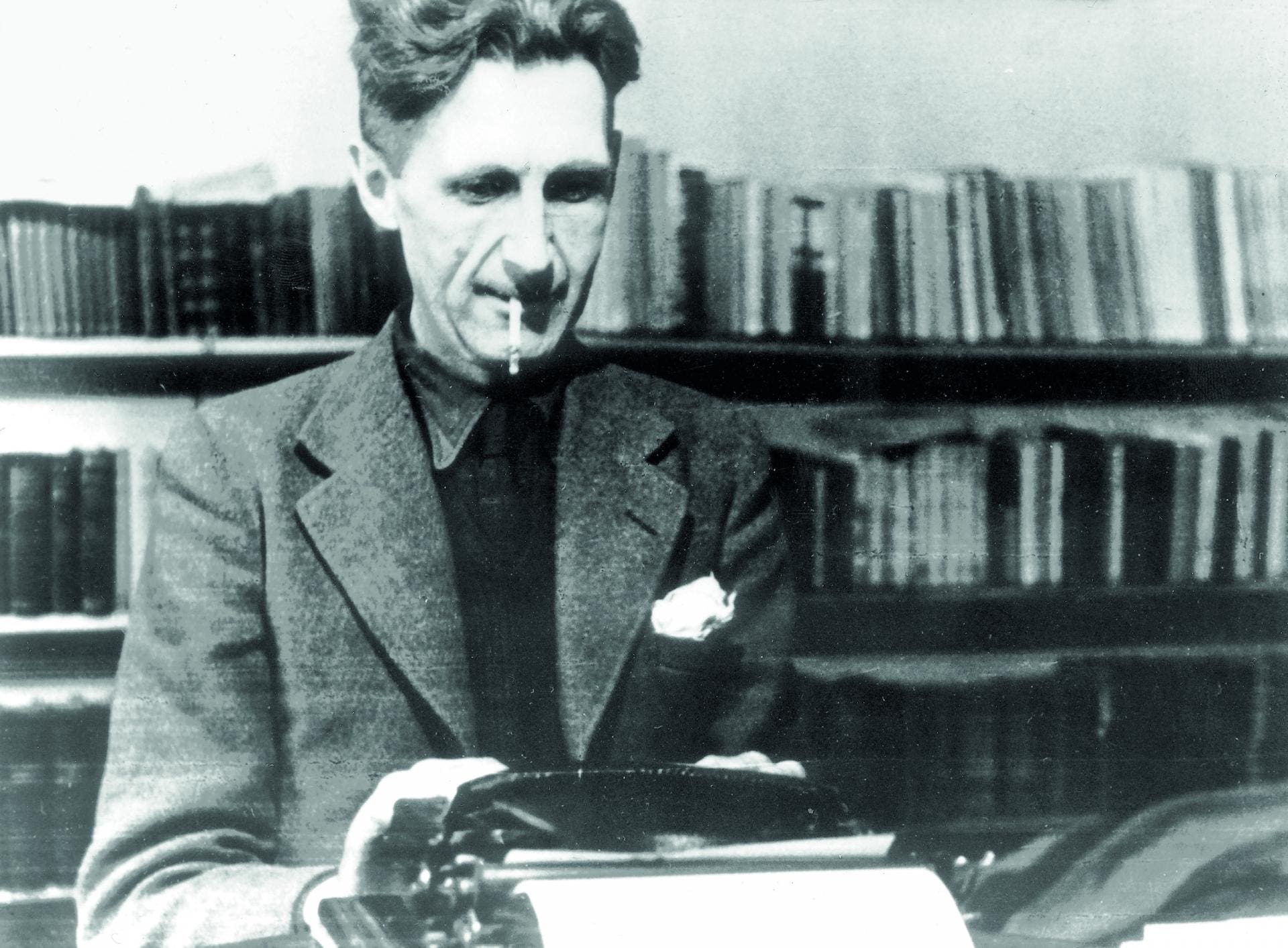

Through the bombings and dereliction, Orwell’s description of a numbingly routine part of daily life in the capital of Airstrip One bore comparison with a very real London; a city in both physical and psychological ruin that he knew first-hand both during and after the Second World War. London’s ravaged state, combined with Orwell’s failing health, played a part in his decision to move to the remote Scottish island of Jura, where he wrote the novel in a remote farmhouse while suffering from tuberculosis. Orwell died from the disease, aged just 50, barely a year after the novel’s release.

But there are still traces in existence of the London that Orwell knew and which figured in his imaginings for the future of the city should a totalitarian system ever manifest itself. Looking like one of Moscow’s Stalin-era skyscrapers, the imposing high-rise Senate House, which stands in the heart of Bloomsbury, was described by Evelyn Waugh in Put Out More Flags as ‘the vast bulk of London University insulting the autumnal sky’. Still the administrative centre of the University of London, the building was commandeered during the Second World War by the government as the HQ of the Ministry of Information.

Orwell worked for the BBC between 1941 and 1943, and his regular broadcasts of war reports and opinions to listeners in India had to be approved by the Ministry before transmission. Although the physical immensity of the building is perfectly captured by Orwell in his fictionalised Ministry of Truth version, there is little to suggest that the writer found his dealings with the real life Senate House as tedious and manipulative as Smith did with its fictional counterpart.

Writing in 1945, Orwell concluded that, ‘any fair-minded person with journalistic experience will admit that during this war official censorship has not been particularly irksome. On the whole the government has behaved well and has been surprisingly tolerant of minority opinions.’

For a more surprising real-life London location we need to peer into Smith’s equally dour domestic life. Dingy, with no heating, plumbing that rarely works and a constant smell of boiled cabbage and old rags, Victory Mansions, Smith’s home, is a dilapidated apartment building where there are telescreens in every room and the imposing presence of the Ministry of Truth building can be seen through the windows. It’s believed that Orwell based this depressing residence on the somewhat more salubrious environs of a seventh-floor flat in Langford Court, an apartment building on Abbey Road in St John’s Wood, where he and his wife Eileen Blair lived for a few months from March 1941. While the East End of London had been flattened in the Blitz, Orwell was amazed to find how unscathed NW8 was. Looking out of the windows of his apartment, which offered a panoramic view of the city, he noticed that the only noticeable signs of damage in this leafy neighbourhood appeared to be the odd church with its spire snapped off in the middle.

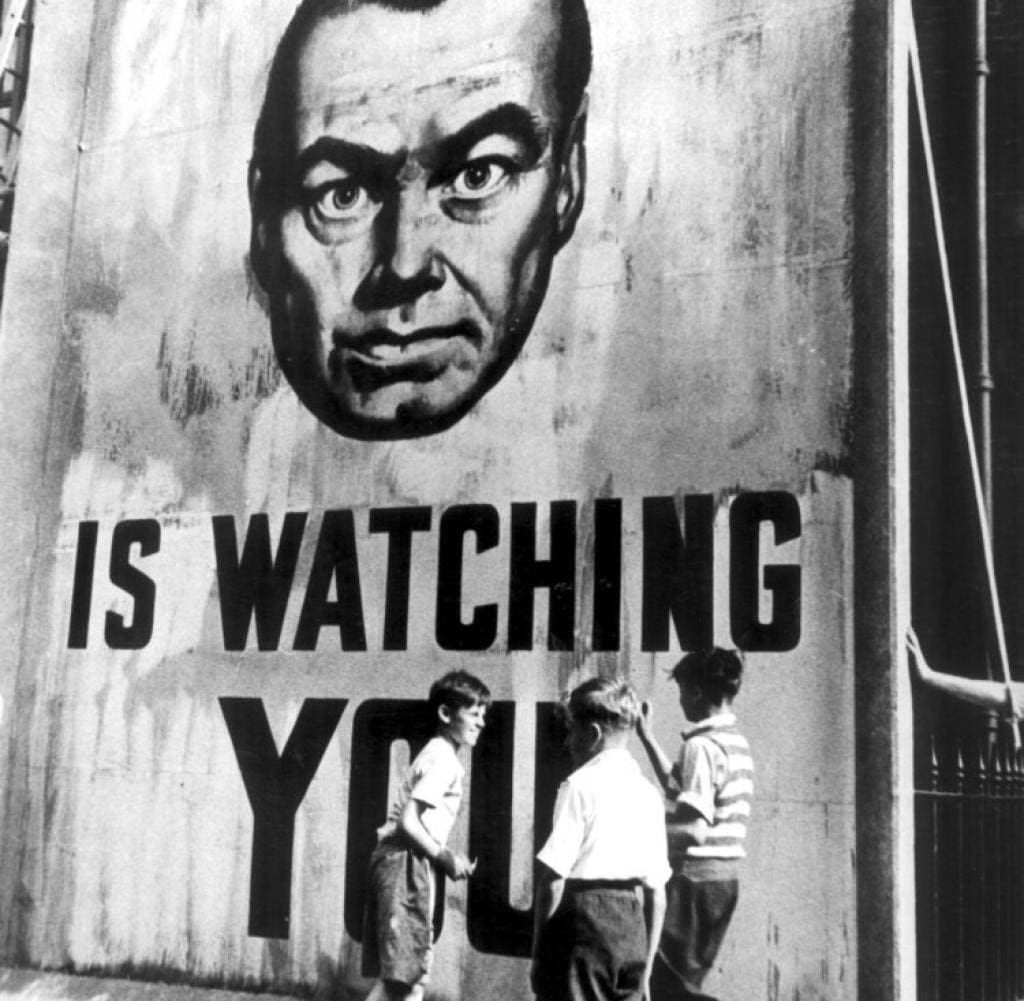

The London of Nineteen Eighty-Four that Orwell created may be stripped of many of its most famous landmarks, but some of the locations in his dystopian vision are survivors from a time prior to the iron rule of Big Brother. Reimagined as a place for public hangings, Victory Square is still recognisable (to readers at least, if not Smith himself) as Trafalgar Square. A statue of Big Brother stands on top of what was, in the dim and distant past, known as Nelson’s column, and the statue of Oliver Cromwell on horseback still stands. Perhaps this society based on terror and discipline still venerates a man whose insatiable thirst for power resulted in the slaughter of so many who stood against him.

There are other, more humble ghosts of an older London that crop up in the novel. Entering a pub in the ‘prole’ quarters, Smith speaks to an old man, aiming to get closer to the truth of what the world was like before Big Brother. Smith is frustrated, however. The old man remembers the House of Lords and ‘flunkeys’ in top hats, but, pressed for details and context, the pensioner’s memory is, Smith concludes, ‘nothing but a rubbish heap of details’.

Smith and Orwell himself did have one thing in common, however. Both were being watched without their knowledge. Smith was monitored throughout the novel by the Thought Police, who eventually would teach him to crush his rebelliousness and love Big Brother. Orwell himself was being watched by members of the Information Research Department, a department of the Foreign Office responsible for counter Soviet propaganda.

Orwell was already a major literary figure, thanks to the publication of his satirical novel Animal Farm, and there was a file on him long before the release of Nineteen Eighty-Four that remained open even after his death in 1950. These papers show that there was a belief that Animal Farm should be published abroad as ‘a very effective piece of political satire’ and that this book, along with Nineteen Eighty-Four should be published in languages such as Sinhalese and Ewe (spoken in Ghana) with the storylines modified to suit each region as part of attempts to stop the post-war spread of communism worldwide. Special Branch was also interested in Orwell, though for very different reasons. Whereas the Information Research Department was exploring how his work could be used to benefit British interests, Special Branch was concerned that Orwell could be a communist himself.

His resignation from the Imperial Police service in India as a young man, and from the BBC in 1943, alongside his writings for left-wing periodicals and his friendship circle of Islington-based intellectuals, led to personal details of his mannerisms being put on file. Clandestine reports describe Orwell as dressing in a ‘bohemian fashion’ though one paper concluded that, although he has ‘strong left-wing views’, he was ‘a long way from orthodox communism’.

Orwell died long before the true impact of Nineteen Eighty-Four was felt. Despite his weekly radio broadcast for the BBC, there is not believed to be a single surviving scrap of audio tape. Therefore we can have no clear idea of what his voice sounded like. His words and a scant collection of photographs are all that remains.

The London Orwell knew has all but vanished, too. What the man himself would have made of surveillance cameras, social media and the re-casting of the terms Big Brother and Room 101 for TV entertainment shows is a topic of inexhaustible curiosity to academics and op-ed writers. But what courses through the veins of Nineteen Eighty-Four and its vision of London is the theme of memory; and whether the most important changes and evolutions the capital goes through are those of physical construction, growth and retraction or the way the human eye perceives it.

‘He tried to squeeze out some childhood memory that should tell him whether London had always been quite like this,’ Orwell wrote in the novel, referring to Smith. ‘Were there always these vistas of rotting 19th-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber, their windows patched with cardboard and their roofs with corrugated iron, their crazy garden walls sagging in all directions? But it was no use, he could not remember.’