The most stylish Federico Fellini films to watch during lockdown

Last year marked the centenary of Federico Fellini who, at his height, vied with Alfred Hitchcock as the world’s most famous director. His prodigious oeuvre remains an inspiration for the likes of Martin Scorsese and Wong

A darkened room, bottomless popcorn, the doors opening at a pre-arranged time – if only lockdown was as straightforward as cinema. But life is messy, a truth that Italian writer-director Federico Fellini examined over two dozen films during a four-decade career. No doubt his centenary coinciding with the silent streets of the epidemic would have appealed to his well-developed sense of the surreal.

Described by critic John Powers as the “cinema’s great laureate of the id”, Fellini wrote and directed the majority of his output, receiving four Best Foreign Language Oscar nominations and winning a Palme d’Or (for La Dolce Vita) along the way.

“I always direct the same film,” he once said, “I cannot distinguish one from the other.” While it’s possible to imagine Michael Bay heaving a heartfelt, companionable sigh at hearing this, a quick glance at Fellini’s filmography demonstrates that a “you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all” label doesn’t stick with the Italian maestro. He began his career during the Italian Golden Age of gritty neo-realist cinema, but after the 1950s his work grew more flamboyant, experimental, and self-referential, reflecting the changing times as well as key western influences like the Marx Brothers and Buster Keaton.

When Fellini says he’s remaking the same film, he’s talking about his leitmotifs and obsessions. Chief among these is the circus (indeed, Fellini claimed to have run away to join a travelling circus when he was only seven). Today, to refer to a film as ‘Felliniesque’ suggests that it has a surreal, carnivalesque essence, a whirling blend of sights and sounds that was typical of a Fellini flick.

It wasn’t all immortal celluloid – when he was off his game (for some, that includes most of his output after 1970) the flair could sag into a morass of weak self-parody and – for today’s audiences – rather cringey sexual politics. Even some of his out-and-out classics like 8 ½ – rated by cineaste bible Sight & Sound as the tenth greatest film of all time – continue to divide audiences, while La Dolce Vita, at the time of its release, almost had Fellini lynched in Milan.

For those that are new to the director, we’ve compiled a list of his films that feel best suited to the current climate. Additionally, a national lockdown feels like a good time for black and white, perhaps reappropriating the colour back into our own stripped-down present.

La Strada (1954)

The tonic for when cabin fever kicks in and fantasies of a post-lockdown nomadic existence begin to appear deeply attractive. La Strada is concerned with the unholy pact between feral Zampanò (Anthony Quinn) and angelic Gelsomina (Giuleta Masina), after she is purchased from her mother for 10,000 lira to act as a kind of Sideshow Bob in Zampanò’s touring strongman show.

It was a breakthrough role for Masina – also Fellini’s wife – who projects an otherworldly innocence with occasional Chaplinesque verve. Quinn, meanwhile, is magnetic as one of cinema’s great jerks – his Zampanò is a self-absorbed giant clad in impulse, rage, and violent habit, quick (ish) with a knife and not adverse to robbing some nuns if the opportunity presents.

La Strada, a stylistic bridge between Fellini’s early Rossellini-inspired neo-realist productions and his later, more picaresque films, brought the writer-director his first Oscar nod – although he nearly didn’t complete filming after suffering a bout of depression during the shoot. Fun fact: Bob Dylan has cited the film as the inspiration for his song, Mr. Tambourine Man.

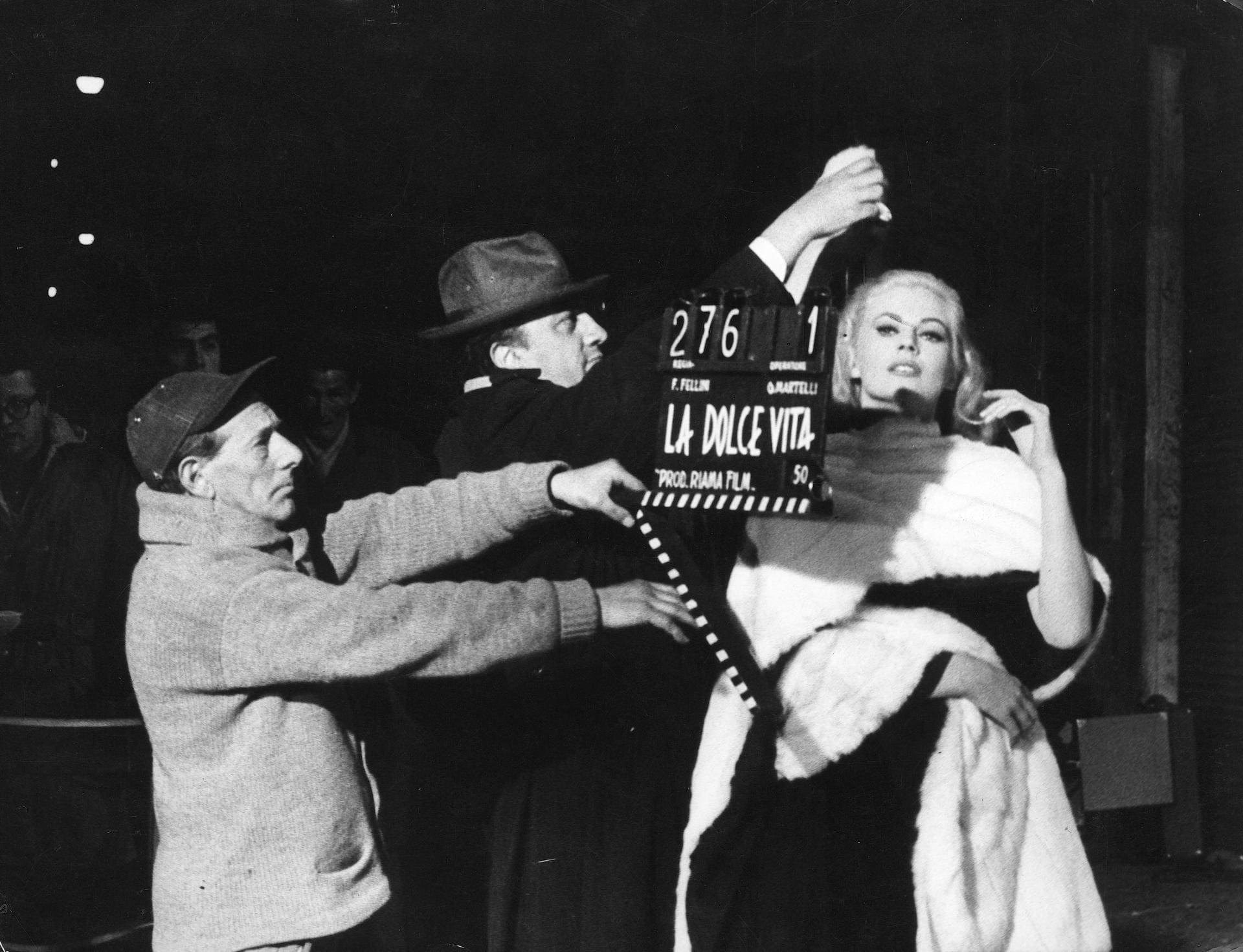

La Dolce Vita (1960)

The choice for those pining after all the parties they’re missing out on. La Dolce Vita is the film most readily associated with Fellini and rightly so, for this three-hour satire of Swinging Rome walks a tightrope between a celebration of the period and an expose of its hollow heart.

We follow Marcello – a gossip columnist played by Fellini-regular Marcello Mastroianni – as he slouches handsomely through an odyssey of self-exploration that transports him through the city’s higher social spheres. While most know the film for that famous Trevi fountain flounce with gravity-defying Anita Ekberg, La Dolce Vita is in fact chock-a-block with striking set pieces and surreal, affecting encounters.

Not everyone loves it; the hard-hearted critic David Thomson described Fellini’s opus thusly: “Nothing happens, except for flatulent set pieces, epic reaches of symbolism, and teary-eyed larger metaphors”. At the time of release, the Vatican’s Osservatore Romano declared the film “an incentive to evil, to sin, to vice” and threatened the faithful with excommunication if they were to see it. What a recommendation.

8 ½ (1963)

Martin Scorsese describes Fellini’s follow-up to La Dolce Vita as a “touchstone” for its, “freedom, the sense of innovation, the underlying rigour and the deep core of longing, the bewitching, physical pull of the camera movements and the compositions”.

8 ½ feels, stylistically, like the natural successor to La Dolce Vita – the episodic narrative reduced in importance to spectacle, producing a film that feels deft, weightless. The actual narrative is a stream of (self) consciousness about a director unsure of how to follow up his great success (with Mastroianni returning to represent Fellini on-screen).

Again, the fractured narrative structure of 8 ½ wasn’t a hit with everyone: at the time of release, a disgruntled Calabrian audience tried to attack a projectionist during a screening. It was around this time that Fellini had become interested in Jungian thought – and LSD – prompting an experimentalism that contributed to marring and making the remainder of his career.

It may well be that 8 ½ is not the ideal choice if you’ve one eye on the film and one eye on virus updates as it can be easy to lose the narrative thread. However, lockdown may be the incentive you require to reach the end of this routinely top ten film of all time and make an informed decision as to whether you’re in the Scorsese or Calabrian camp.

The City of Women (1980)

Perhaps the most controversial choice in this selection – both critically and in terms of subject matter – ‘The City of Women’ was released when a sixty-year-old Fellini was trying to rediscover his mojo in a world of rapidly evolving sexual politics. It’s a distinctly odd, rather uneven piece, in which the men come across as calcified caricatures while the women are a furious, united force, ready to take shape into something vital and renewed.

Seen from the perspective of Snàporaz (Mastroianni essentially reproducing a slightly older Guido from 8 ½), the film tracks this ageing seducer as he disembarks a train to enter a feminist fantasia. In the woods, Snàporaz happens across what would today be called an ‘eco retreat’ where lively young women beat the seven bells out of a male dummy or sing rousing songs about how essential a man is to a woman (the answer: like a somersault without a rifle).

Fellini described this cirque-de-sexual-politics as a fable, and it’s one of his most well-controlled absurdist pieces, with memorable characters like the arch seducer Katzone (played by Ettori Manni) with his supersonic vibrator, freaky touches like Mastroianni having his ear licked by a glowing wall-mounted mask, and a trial scene with tricky questions from the prosecution like: “Why did you choose to be born male?”

The seed of the film had emerged ten years earlier as a collaboration with Ingmar Bergman, and during its torturous progress to the screen it’d seemed to many – Fellini included – that it might never be realised. For many feminists now and then, that might have been the preferred outcome, and Fellini was sincerely surprised at the negative responses, claiming to have completed his due diligence and consulted with feminists over the script.

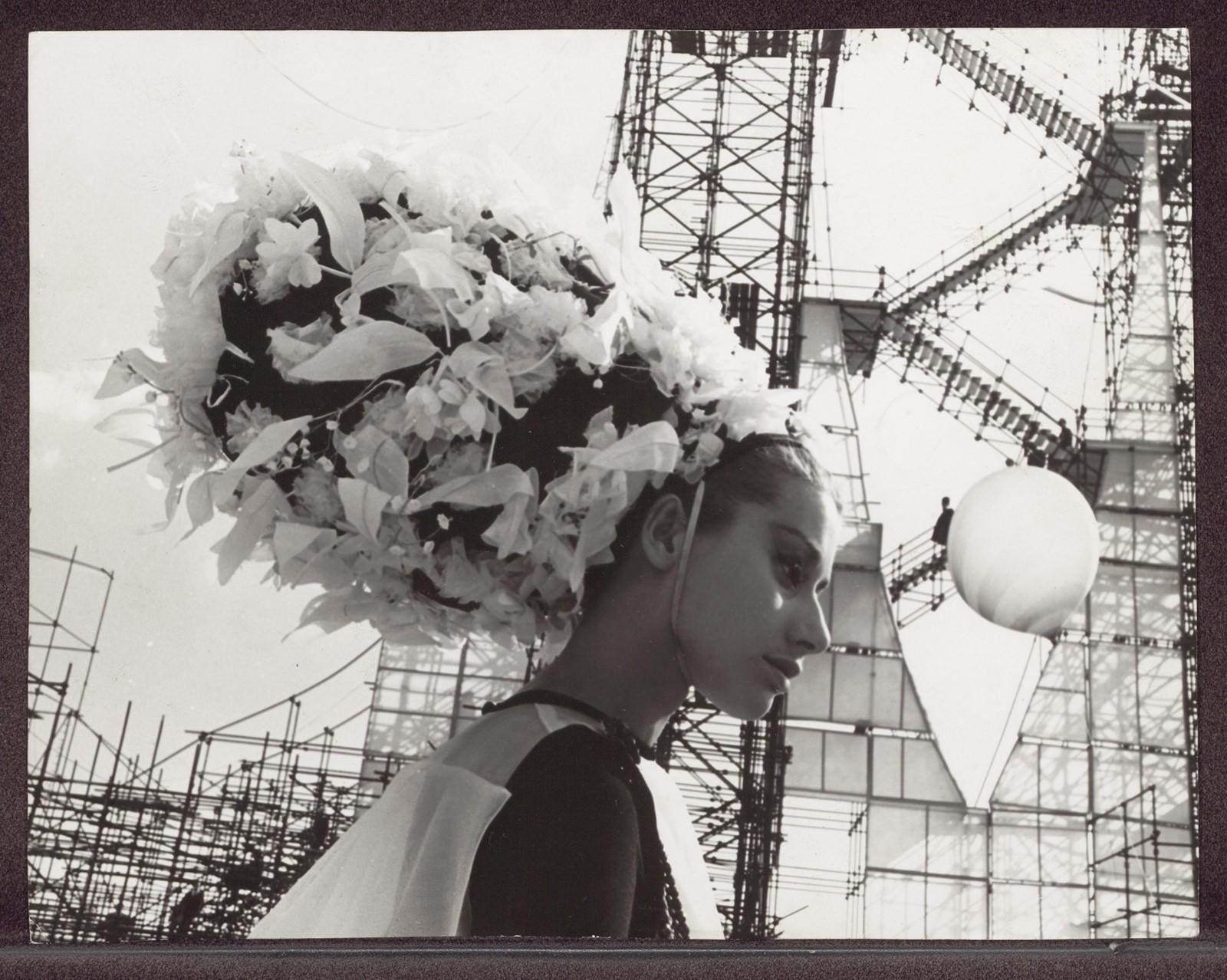

And the Ship Sails On (1983)

While a film set on a cruise ship might not seem, at first glance, ideal viewing for the coronavirus pandemic, And the Ship Sails On represents a late career success for Fellini (and received a fifteen-minute standing ovation at Cannes, no less). After the general hullabaloo that greeted The City of Women, this, his next film, returned the light touch, carnivalesque cinema that represented the auteur at his best.

Set on the eve of World War I, a group of aristocratic passengers – mostly plucked from the world of opera – have assembled on the Gloria N. luxury liner to bid their farewells to a recently deceased diva. Egos and rivalries rub up against one another until the ship encounters a contingent of Serbian refugees who require urgent assistance.

With a set concocted entirely within the walls of Fellini’s beloved Cinecittà Studios in Rome, this highly stylised production has only the loosest interest with plot, the director instead chiefly engaged in joyfully skewering the self-regard of artists while also more subtly critiquing the Belle Epoque. Opera buffs will appreciate the remixes of famous scores, while the striking opening sequence – when the film moves from sepia-tinted silent film into full sound and colour – demonstrated that the old dog could still learn some new tricks.

Most of all, however, as the operatic carnival sails on, the film is a reminder that in life you’re in a situation over which you have, at best, only an illusion of control. Best to follow the example of the protagonist Orlando who, despite an encounter with an Austro-Hungarian battleship that doesn’t end well, remains cheerful. In the words of Monty Python, those other arch-absurdists: always look on the bright side of life.

Juliet of the Spirits (1965)

In the week prior to commencing the film, Fellini said he had received a curious dream. In the dream, his right eye was apparently gouged out by someone with a spoon. Attempting to deconstruct the significance of this bizarre vision, he thought that perhaps his right eye, one which represented reality, would not be needed and instead, his left would take precedent – which for him was the eye that represented fantasy. Thus begins the wildly abstract nature of the picture, which follows protagonist Giulietta on a mission to unravel her husband’s fidelity (or lack of), weaving a kaleidoscopic menagerie of dreams, visions, and memories.

Fellini’s first colour feature, the film is generally considered to mark the beginning of his decline. It is significant however because according to lore, it was created as a gift to his wife – which is all the more extraordinary upon discovery that Giulietta is played by Fellini’s actual wife, Giulietta Masina. As Roger Ebert pointed out in his review, La Dolce Vita and 8 1/2 were ‘autobiographical laments about his own problems’. Juliet of the Spirits put a spotlight on Giulietta, revealing much about Fellini’s relation to the feminine mystique and his intimate life. What Masina thought about her husband’s gift is anyone’s guess. After all, don’t we tend to gift to others what we want ourselves?