Frescoes and friction: The true story of Raphael vs Michelangelo

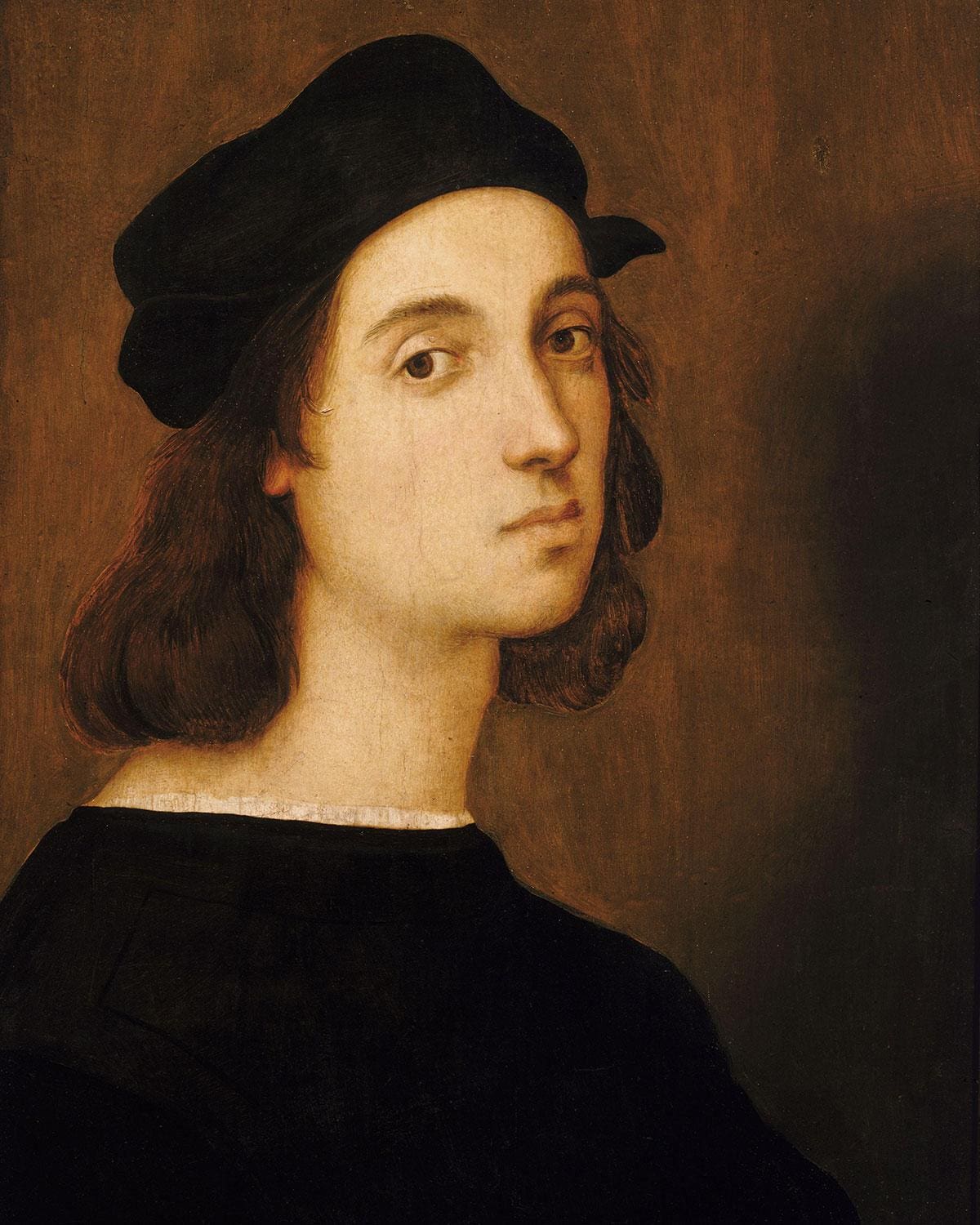

As the National Gallery hosts one of the first exhibitions to explore the complete career of Raphael, isn't it high time we reconsidered the standing of the high priests of the High Renaissance?

Deep inside the Vatican in the centre of a fresco is a portrait of the most miserable-looking man in the Holy See. Located inside the quartet of suites known as the Raphael Rooms within the Apostolic Palace, the School of Athens fresco is a boldly coloured, possibly over-restored, depiction of the greatest scientists, mathematicians and philosophers from classical antiquity, all gathered together, discussing and sharing ideas.

Plato and Aristotle take centre stage on a wide set of marble steps, with a huge, triumphal arch framed behind them. Plato is pointing at the sky and holding a copy of his book Timaeus. Aristotle looks toward the ground, perhaps an indication of his preferred interests in studying only what is observable to the human eye. Socrates (pre-hemlock poisoning, of course) and Pythagoras are all among the crowd of polymaths, most looking suitably content and energised by the hubbub of debate.

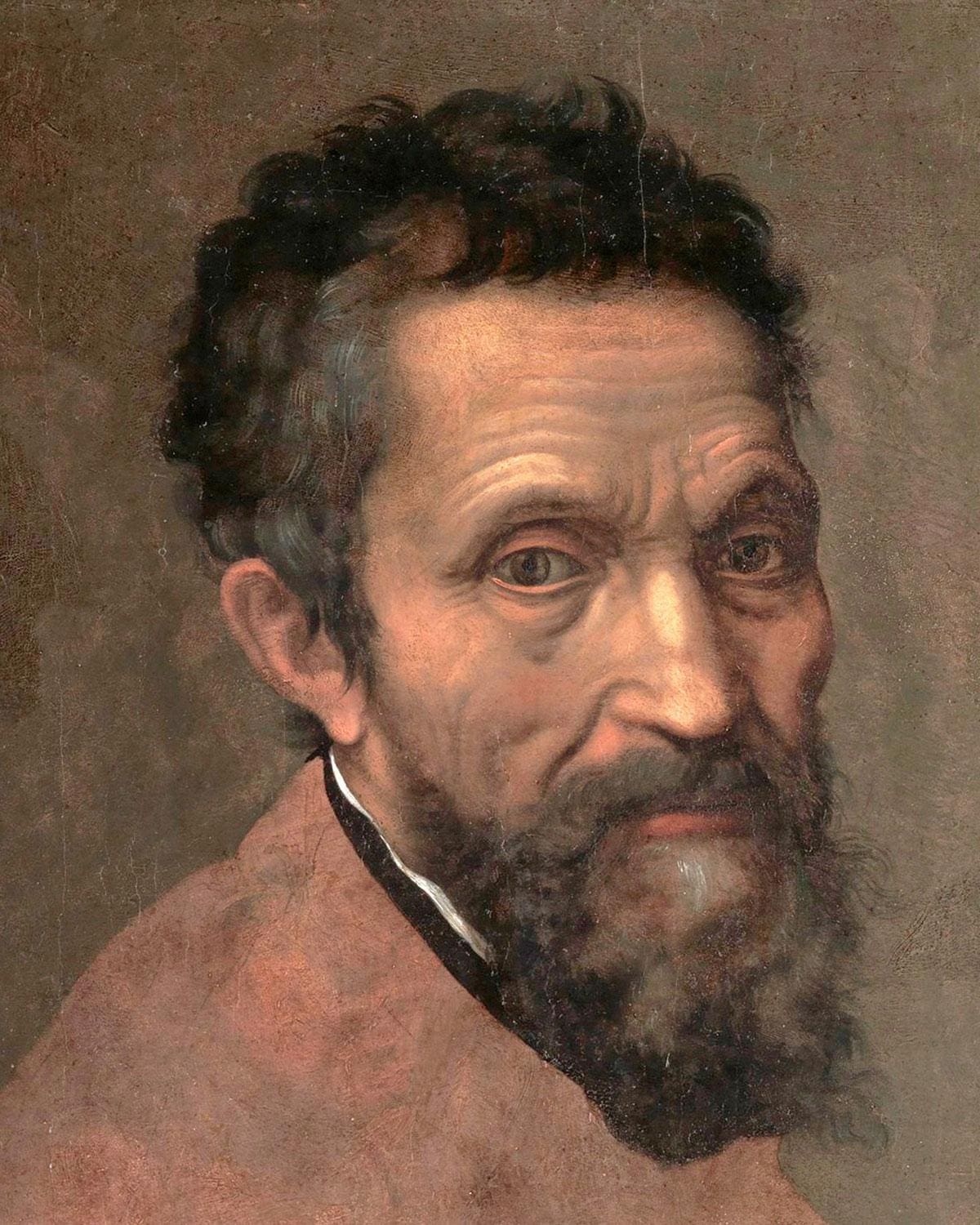

But there’s an exception to the intellectual bonhomie. Sat on a step, head bowed, clad in drab robes, looking like he might be about to get up and ask the other men for some spare drachma for something to eat, the man scrawls away petulantly in his notebook, using a block of marble as a makeshift table. This is Heraclitus, a pre-Socratic philosopher who wrote on themes of universal change, once saying that ‘you never step in the same river twice’, a phrase that may have contained more contextual depth at the time than it would ostensibly seem to hold today. Also known as ‘the obscure’ and ‘the weeping philosopher’, Heraclitus’ unkempt mop of dark hair and rangy beard projected a likeness to someone far more familiar to the High Renaissance devotees who would have trooped past the fresco when it was completed in 1511.

|  |

Unmistakably, Raphael had decided Heraclitus should take on the physical form of Michelangelo, a man who at the time was also in the Vatican City, working on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But this inclusion of a thinly-disguised Michelangelo wasn’t meant as a tribute to a fellow Renaissance genius. Known as the most bad-tempered, miserable, irascible man in Ancient Greek philosophy, Raphael’s choice to make Heraclitus look like Michelangelo was a statement with the intention of making sure that nobody who viewed this painting could be in any doubt as to his opinion of his Renaissance rival.

The story of the enmity between Raphael and Michelangelo adds a human element to our understanding of the lives of painters who seem to have ceased to have ever existed as mere men of flesh, amplified, as they now are, into a stratosphere of deified worship that borders on unearthliness. Yet Raphael and Michelangelo were, just like all artists, men of egos, passions, eccentricities and petty jealousies; all of which came into play within an intense competitive rivalry between the elder painter from Caprese and the man he considered to be an upstart from Urbino.

When the man born as Raffaello Santi emerged onto the Renaissance scene in 1504, there was no doubt that his methods were hugely influenced by Michelangelo, already an established master of the form. Raphael’s highly intricate style was an immediate success and the young painter gained the most powerful sponsor possible in the form of Pope Julius II, who, at the time, was looking for someone to paint frescoes in his private library inside the Vatican.

To the immense opprobrium of Michelangelo and fellow Renaissance big beast Leonardo da Vinci, the younger man won the commission from the strong-willed, stubborn pontiff who, during his tenure, transformed Rome from a hovel of medieval warrens into the Eternal City of harmonious piazzas and handsome palazzos.

The critics of the time even began to claim that the young Raphael’s library frescoes were ingenious enough to have bested Michelangelo at his own game. Giorgio Vasari, the art critic and author of The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects was born while Raphael was creating The School of Athens and, never shy of painting an overly hagiographic pen portrait, 40 years later wrote: ‘Raphael of Urbino had risen into great credit as a painter, and his friends and adherents maintained that his works were more strictly in accordance with the rules of art than Michelangelo, affirming that they were graceful in colouring, of beautiful invention, admirable in expression, and of characteristic design… For these reasons, Raphael was judged… to be fully equal, if not superior, to Michelangelo in painting generally, and… decidedly superior to him regarding colouring in particular.’

High praise indeed, written, as it was, during the time when Michelangelo was engaged in the process of painting the Sistine Chapel. The older artist, quite understandably, despised the idea of anyone challenging his status as the supreme high watermark of Renaissance art.

Raphael, it must be said, wasn’t above stooping to less than honest means in order to keep an eye on his competitor. While Michelangelo was painting the Sistine ceiling, the papal architect Bramante was charmed by Raphael into opening up the locked doors of the chapel so that he could take a sneak peek at what his established rival was up to. Duly impressed by the Adonis-like muscularity of Michelangelo’s figures, Raphael, as claimed by Vasari, promptly returned to his own frescoes and beefed up the pectorals of his subjects.

As the 20th-century American art critic Robert S. Liebert wrote in his study, Raphael, Michelangelo, Sebastiano: High Renaissance Rivalry, Michelangelo ‘made Raphael bear the brunt of his unrelenting envy, contempt, and anger.’ The death of Pope Julius II in 1513 and the succession of Pope Leo X continued the trend of papal favouritism towards Raphael. The new pope was said to be particularly charmed by the Urbino painter’s warm and sensual personality, at notable contrast with Michelangelo’s sullen persona and frequent fits of pique.

Michelangelo’s sense of ire was only inflamed further when an ambassador made an announcement that the Sistine Chapel had been decorated by none other than Raphael. This quite astonishing blunder was compounded further by Raphael winning commission after commission; including tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, portraits of popes and frescoes for the sumptuous villa of financier and art patron Agostino Chigi, now known as Rome’s Villa Farnesina.

Based on personality alone, regardless of professional rivalries, the two painters were never destined to be friends. Not only did Michelangelo’s bad temper make him a difficult man to have a working relationship with, but his personal life was also one of almost monastic gloom. A devout catholic, Michelangelo would sleep with his clothes and shoes on and eat ‘only out of necessity’ rather than indulging in any epicurean pleasures. Also struggling with his repressed homosexuality, it’s easy to imagine the older artist being just as jealous of his younger rival’s easy-going manner and sybaritic lifestyle as he was of his skills with oil and canvas.

It would be Raphael’s love of carnal pleasure that would prove fatal. In 1520, at the age of just 37, Raphael died from what contemporary accounts claim was a fever caused by overly exertive sex with his mistress, a woman depicted in the artist’s Portrait of a Young Woman (1518-1519). Despite his bouts of extra-marital passion inside the Vatican, Raphael’s posthumous reputation remained unsullied. The entire city of Rome mourned his passing and he was buried in a marble sarcophagus in the Pantheon, where (in Latin) the inscription reads: ‘Here lies that famous Raphael by whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived, and when he was dying, feared herself to die.’

But if Rome was expecting a conciliatory tone from Michelangelo they would be disappointed. Already partially responsible, due to their own ongoing feud, for Leonardo da Vinci quitting Italy for good four years earlier, the cantankerous veteran (he was then in his late 40s) spent the ensuing decades inflating his reputation as a man with a chip on both shoulders for whom death was no reason to shrug off a grudge. 22 years after Raphael’s passing, Michelangelo wrote: ‘What he had of art, he had from me.’

The elder painter, remarkably for the age, clung onto life until he was almost 90. And, half a millennium on, it is Michelangelo who seems to have won the legacy battle to be known as the greatest painter of the Renaissance era. Michelangelo’s equal genius as a sculptor, coupled with his awe-inspiring frescoes and paintings have undoubtedly been the beneficiary of greater praise than Raphael’s work. Perhaps, by comparison, we prefer the grandiosity of Michelangelo? Maybe Raphael is now considered too much of a nice guy? His paintings, so gentle, beautiful and dreamily amorous, could be considered too lightweight compared with the rich, vast, full-fat, almost fin de siècle, feel of Michelangelo’s works.

The current National Gallery exhibition could be the right time for the man from the backwater of Urbino to regain his status as every bit Michelangelo’s equal. His ability to bring soothing, gently carnal rhapsody to his viewers could not have come at a better time.

As Desiderius Erasmus, philosopher of the Northern Renaissance, living in the Netherlands at the time when the two bitter rivals were snarling at each other in Rome, wrote: ‘Give light, and the darkness will disappear of itself.’

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Raphael runs at the National Gallery until 31 July, tickets from £24, nationalgallery.org.uk