Rankin: Three Decades of Trailblazing Photography

"I think I have honesty Tourette’s, which doesn’t always go down well."

“I’d like to go to a Gucci party and feel part of it all,” says Rankin. “But I don’t. I’ve always felt on the periphery of the fashion industry. I’m seduced by it, of course, even though I know it’s shallow. But I’ve just never felt part of it – a bit too fat, not as good looking. I think I’ve always felt like an outsider.”

It’s an odd thing to hear Rankin say, on more than one count. After all, he epitomised the heady excesses of London’s independent fashion publishing boom of the 1990s. He co-founded the influential Dazed & Confused magazine straight out of college, garnering the kind of reputation for untrammelled cocksureness that, he says, “will definitely influence some people’s decision about me even now. I was crazy and arrogant then, and that sticks”. The celebrated photographer has spent three decades in the fashion world – a period he has documented in a new book, the self-critically titled Unfashionable, a collection of his best imagery.

“Yeah, I think the feeling of being an outsider comes from knowing I never had the right background, that sense of coming from nothing – though it’s even worse now, you really need that silver spoon,” he says. “I was just this lower middle-class kid from Glasgow by way of St. Albans. But then I think that gave me an advantage too – I had this clean sheet of paper to start with.”

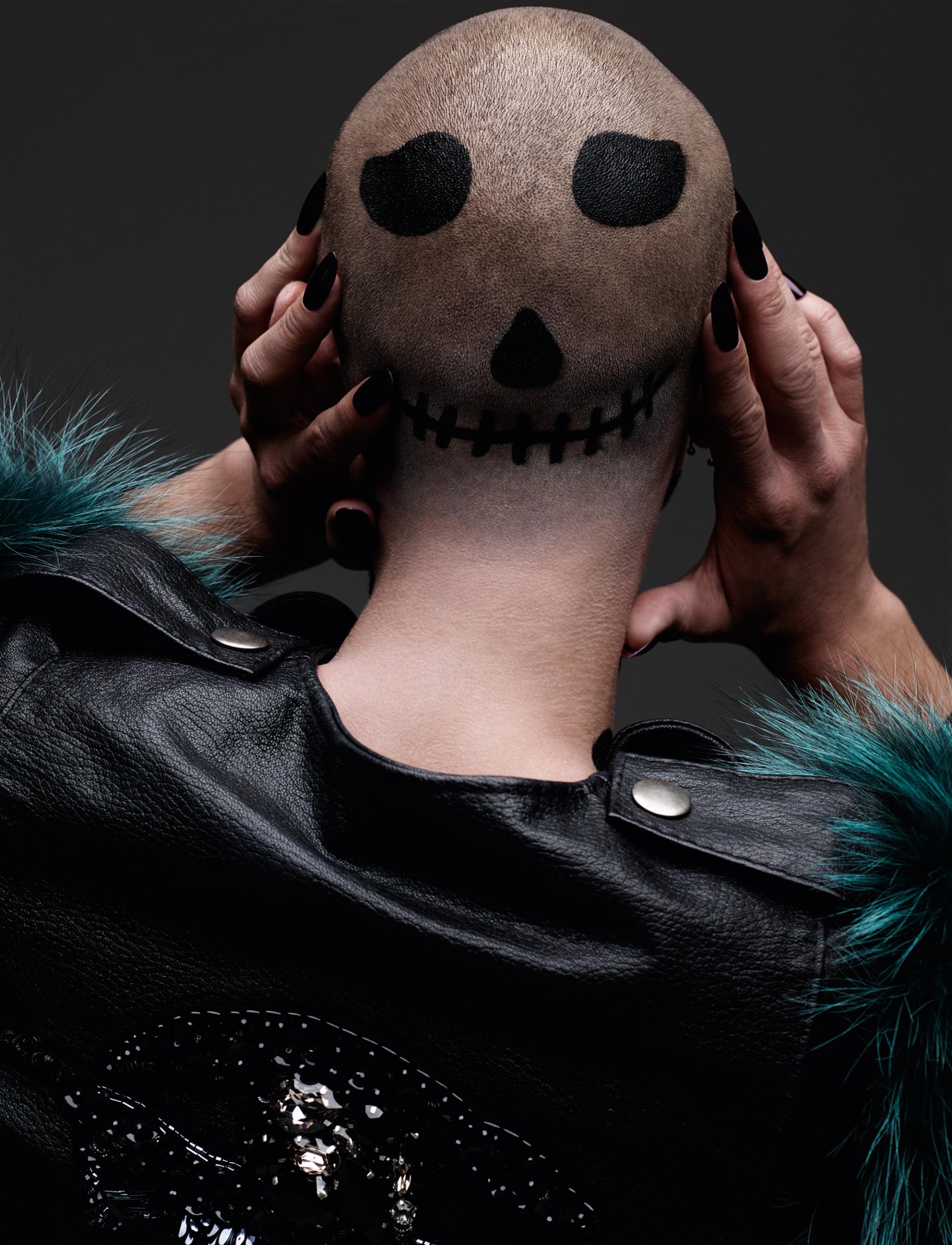

Winnie Harlow for Hunger Magazine, 2016

It’s a sheet that the Kentish Town-based photographer and director has certainly scribbled on and folded up in his own distinctive way: fashion images that are rarely just about fashion, but contain some undercurrent of commentary or perhaps cheek; advertising campaigns for the likes of Dove, Diesel and Aston Martin that often stay fresh far longer than the products they’re promoting; videos for the likes of Miley Cyrus and Tinie Tempah; portraits, be they of Michael Jackson, Mikhail Gorbachev or HM The Queen, that crack the PR veneer – even getting Her Majesty to crack a smile.

“It pays to be inquisitive, to make [your subjects] laugh,” explains Rankin, “and to always remember that it’s a collaborative process – they need to feel like they’re part of it. Besides which, isn’t it rude to take something from someone, even their picture, and then not let them be part of it?” No wonder Rankin has become a brand in his own right – John Rankin Waddell reduced and packaged as a one-word moniker, like Pelé or Madonna.

However, he admits that even now, when he’s up for an advertising campaign, he feels as though he’s “blagging it”. “I think a lot of creatives live with the feeling that they’re going to get found out,” he says. “I like to think my work is very humane, which makes it different to other ‘fashion photographers’, though I hate that expression. Even when working for brands, for me it’s about trying to make a connection. I’m a pop photographer, pop as in a bit in your face but more so pop as in populist. I’ve never understood why you should ever have to read a text to understand a photograph. I don’t get that. And I don’t think commerce is a dirty word, though a lot of photographers still do.”

The book is more than a benchmark of Rankin’s career. It comes at a time in his life – he’s now 52 – when perhaps he’s feeling a little more contemplative. “Milestone? The book is more like a tombstone,” he laughs. “It’s weird because you look through the fashion shots and think ‘Wow, I’ve done quite a lot’ and then a second later you think ‘Whoa, I’m really old’. It’s nice to go down memory lane, but it’s also a reminder that there’s a new generation behind you and the world is changing.”

And not, Rankin argues, entirely in a good way. He’s a more serious thinker than perhaps his public image allows for – and he’s certainly not happy with social media. “Not for the same reason as David Bailey, who said ‘it just means a lot more shit images’,” Rankin chuckles, “although I do think images today are more powerful and yet at the same time less insightful. Images are proliferating but they’re mostly a form of branding in effect. It’s at a place which is the complete opposite of why I wanted to get into the medium.”

Social media, says Rankin, has completely transformed the business he’s built a career from. Creativity and imagination, he argues, have given way to accountants and data analysis, to chasing hits over vision. “Combined with a celebrity culture that’s out of control, we’re now in a position where some people have a worrying amount of power – a place in which someone like Kendall Jenner has more people following her than the population of many countries… Generally people won’t tell someone with that kind of power that their ideas are sh*t.”

Rankin, it seems, is an image-maker genuinely concerned with the runaway train of image-making. “I think social media is a very negative thing that people – and brands – will in time have to start to thinking about ethically.” He has spoken at conferences on the subject and has tried, unsuccessfully so far, to get backing to shoot a documentary on the issue. “It’s the cause of mental health problems, it’s been designed to be addictive, so I get why some people say it’s evil. I’m in my 50s and I find it addictive, so how is a 14-year-old going to feel about it? What I find weird is that when I post something, within five minutes half a dozen people have commented on it. That’s crazy. What are they doing? In time social media will come to be seen like plastic – it will be a more debatable subject. But right now people are scared to question it. ‘Social’? F*** off, it’s not about connecting. It’s about isolating.”

All of which might make Rankin sound like a reactionary middle-aged man, which, in all honesty, he’s not – rather, perhaps, a man who’s simply shaken off a youthful wildness (“it’s easy for me to feel like a d*** because I’ve been a d*** most of my life,” he says) and is ready to use his cultural heft to change things, to back the things he sees as being worthwhile.

“Looking back at Dazed, it was like we were all in a band and we broke up because there were too many egos. That wouldn’t happen now, though I do feel that self-belief is very important. You have to believe in your ideas, but also be very critical of them too, which isn’t something that I think can be taught, and which, again, maybe comes from my background,” says Rankin. “Before we put anything out now it’s really jumped through the hoops, so it’s ready. By the same token you have to support others’ good ideas when you see them. The creative world is inherently not into doing that, maybe because it’s hard to make your way up in that world and, when people get there, they tend to be protective. There’s a jealousy – ‘I wish I’d had that idea…’”

He adds that there’s “a lot of bullshit in the fashion and advertising industries. That hasn’t changed. It’s probably got worse. And I think over time that teaches you to really try to be honest. I think I have honesty Tourette’s, which doesn’t always go down well. When I was about 15, my mum told me to choose a job you love and you’ll never work a day in your life. That was the best advice she ever gave me. But, really, you have to remind yourself how lucky you are. And you just can’t take it all seriously. You have to make jokes and recognise the absurdity of what you’re doing. And it really is absurd at times.”

Rankin: Unfashionable – 30 Years of Fashion Photography, £50.00, is published by Rizzoli