King of kink: the photographic legacy of Helmut Newton

Hardened under a shell of classy, worldly, almost intimidating glamour, Newton’s pictures hint at complex, psycho-sexual associations that are never quite revealed

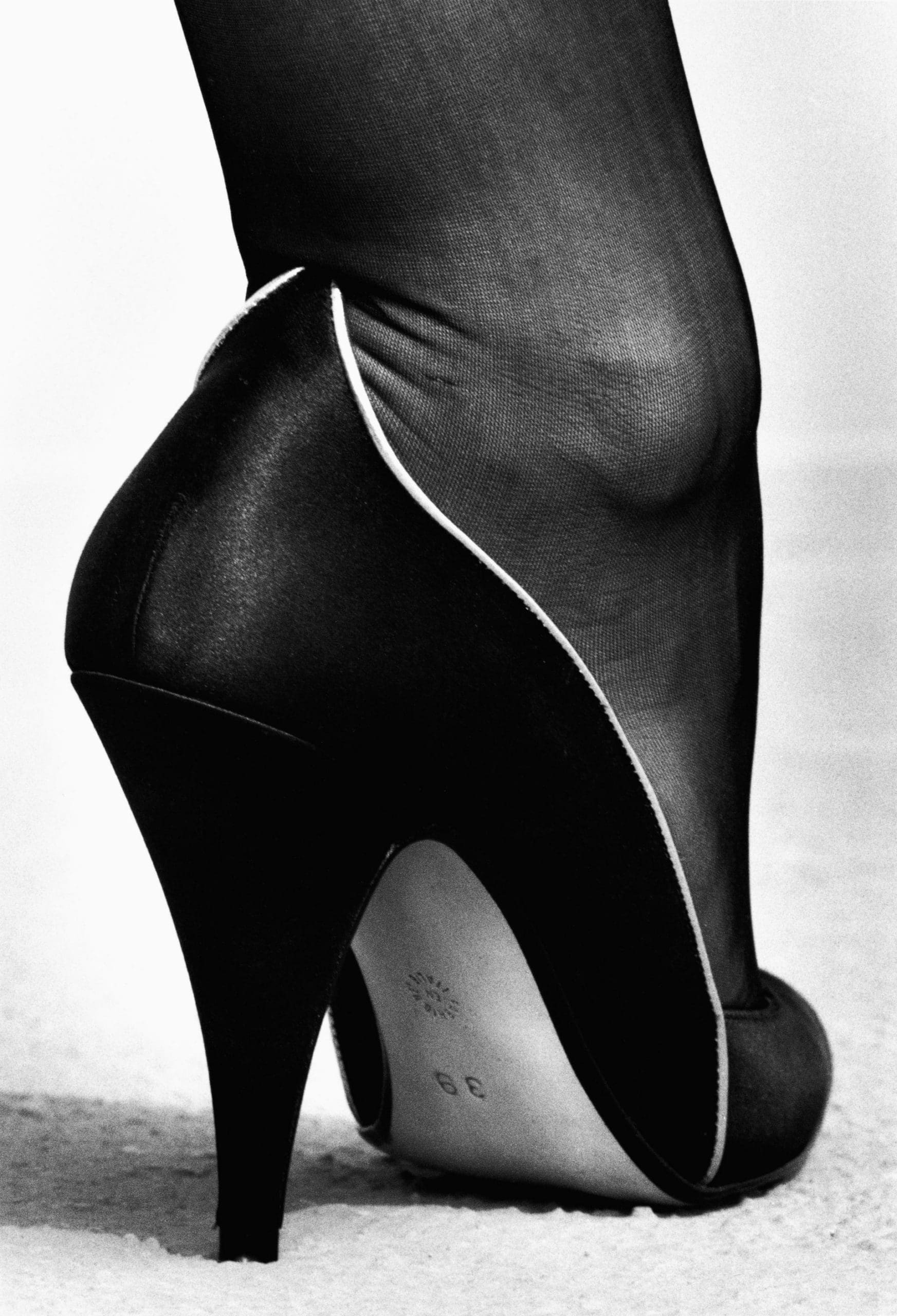

“Sex is deadly serious. Otherwise it’s not sexy,” suggested the photographer Helmut Newton, who died in 2004. And he might well know: born in 1920 and raised amid the glamour of inter-war Germany, sex and decadence seemed to be all around the young Helmut Neustedter. He bought his first camera, a Box Brownie, at 12 and, “from the age of 13 I was surrounded by the images of Nazi Germany,” Newton said: elegant women in dark, sharp tailoring and silk stockings, the flags and uniforms, rallies and spectacle, the urbane, tantalising sophistication of high tea and Mozart amid brutal revolutionary change.

The only child in his class to be driven to school by chauffeur, when Newton lost his virginity at 14 his mother raised his pocket money so he could buy condoms – advising that he should only have sex once a week so that he would not neglect his homework. “All you can think of is girls and photos,” his father would complain. Newton would combine those twin interests: at 16, he was apprenticed to photographer Elsie Simon, whose specialities were show-business portraits – and lingerie catalogues. That certainly informed Newton’s characteristic style: highly sexualised and theatrical, occasionally flirting with the bizarre, often portraying women as either decidedly in charge, or decidedly there to meet the male gaze, depending on your viewpoint.

The centenary of Newton’s birth was marked this March with the launch of HELMUT NEWTON 100, an exhibition at Newlands House in Petworth, West Sussex. Designed as an online sister to its physical counterpart, INSIDE HELMUT NEWTON 100, will launch with a short film on IGTV, as well as the gallery’s Facebook account at 3pm on Thursday 30 April.

Last year, one of Newton’s best-known black-and-white images, the diptych ‘Sie Kommen!’, first seen in French Vogue in 1981, sold for US$1.82m, not just a record for Newton, but one of the most expensive photographs ever sold. But while some of the clothes in his images have certainly dated, has Newton’s vision fared better over the years?

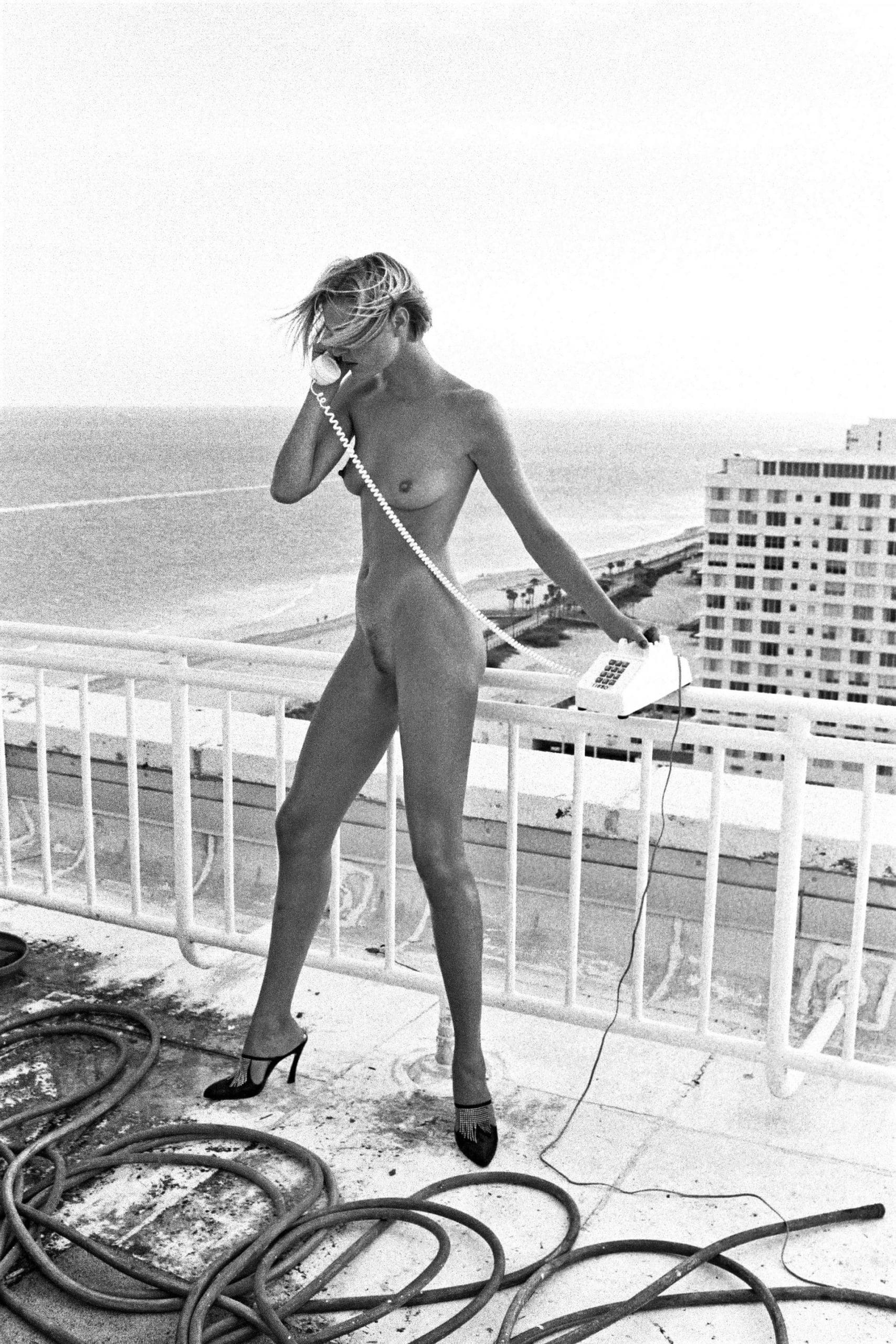

“There have always been those who thought he was exploitative because of the nature of his images – or that he blew apart the fashion industry’s attitude to women with his explicit, noir images. And I’m of the generation that feels the latter,” argues Laura Paterson, head of photographs for Bonhams. “Newton’s women were portrayed as those who would chew you up and spit you out. These are not wishy-washy women at all. There’s no reason for these images to be scorned.”

Paterson concedes that Newton’s pictures – nearly always shot in natural light, never subject to post-production manipulation, rarely even cropped, often with a reportage feel – are not necessarily easy images to live with; and that the idea that they tend to be bought by single men, post-split, post-divorce, is not far from the truth. This might seem to diminish her argument that Newton above all represented powerful women – Paterson notes herself – but “from a photographic historical point-of-view alone, Newton’s best work changed things”.

It allowed fashion photography to be viewed as art for the first time – and for J.G. Ballard to compare Newton with Francis Bacon – taking it out of the realm of the fawning soft focus and giving it a graphic, contemporary edge. “And while it’s easy to look at his photographic treatment of women, of nudes, and see that’s it’s dated, that’s only because we’ve become accustomed to that kind of image. But they were really provocative then,” stresses Jude Hull, Christies’ specialist associate director of photography.

“These are sexy images but I’ve never felt they objectify women,” she adds. “Actually there’s a lot of [other photographers’] work out there in which the nudity is gratuitous. Newton’s work goes beyond just being of sexy women – they’re powerful in terms of their composition, for example. They hold a wall, which is important to collectors. And I think the market attests to Newton’s continued relevance.”

Certainly sales of Newton’s pictures at auction have remained robust – Christies reports a remarkably consistent 80 per cent sell-through of any Newton work it offers, with prices typically in the $20,000 to $30,000 range, prices holding up despite (or perhaps because of) any controversy that might surround them.

“I appreciate that younger generations might not get Helmut Newton,” Paterson suggests, “but it’s important to remember that these images are very much of their time. Much of Newton’s work is really quite mischievous. Maybe we’ve lost our sense of humour [in our assessment of Newton’s work] a little.”

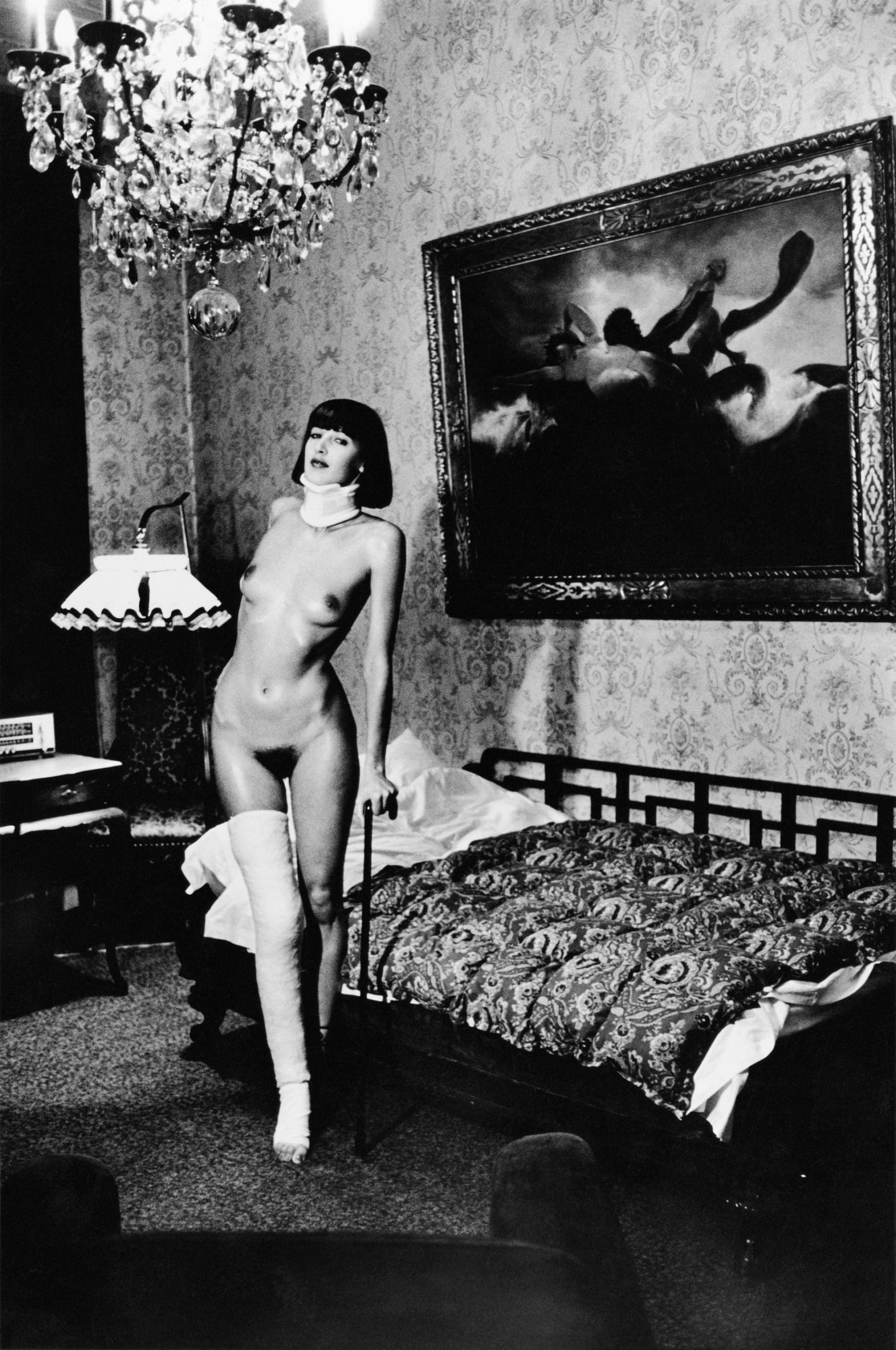

In his lifetime Newton – on occasion dubbed ‘the King of Kink’ or ‘the Marquis de Sade of lensmanship’ – always dismissed any accusation that his intentions were misogynistic or pornographic. “Bullshit,” he called it. “A nude is not pornographic”. Newton, who was inspired by the exactingly lit and posed glamour photography of George Hurrell, admitted that some of his images de-personalise the models. “I like a certain cold look,” he would add. But he hardened his pictures under a shell of classy, worldly, almost intimidating glamour that separates the imperious women pictured from the merely titillating. They hint at the story of complex human relationships that is never quite revealed; there’s some unreadable psycho-sexual game afoot.

Newton may have revelled in the notoriety that his nudes brought him. When fashion magazines received notices of cancellations to subscriptions, with withdrawal of advertising support – which would happen as late as the mid 1990s – or letters of complaint after one of his shoots had been published, he would request that the letters were saved for him. His nudes may allude to a harshly erotic, ‘Cabaret’ aesthetic, but for the photographer they were, ultimately, tongue-in-cheek.

Highly-charged images of nudes stuffing chickens, wearing saddles, working in the kitchen while in bondage or handcuffs, playing dead or wounded, in wheelchairs and plaster-casts – a health warning about the dangers of wearing high-heels, Newton quipped to one detractor – they straddle some fuzzy line between the wry and the challenging, the mocking and the dark. Their production had a clinical quality to them as well – Newton would never touch his models, insisting that his photographer wife of 56 years, June, made any adjustments to clothing or pose.

“When you see them [his nudes] you should feel that, under the right conditions, they’d be available,” Newton once said. “Maybe it would cost a lot of money, maybe it’s a matter of timing. Who knows? [With fashion photography] there’s always been a line you aren’t supposed to cross. But I’ve always stuck my neck out. I seem to have been on the razor’s edge all my life. [But] I like strong women. I like women who are overwhelming.”

INSIDE HELMUT NEWTON 100, will launch with a short film on IGTV, as well as Newton Gallery’s Facebook account at 3pm on Thursday 30 April; Instagram: @newlands.house.gallery; Facebook: newlandshouse.gallery; Website: newlandshouse.gallery #NewlandsHouseOnline