A true icon: In conversation with celebrity photographer Andy Gotts

The prolific photographer talks sticking to your guns, big breaks and his recipe for success

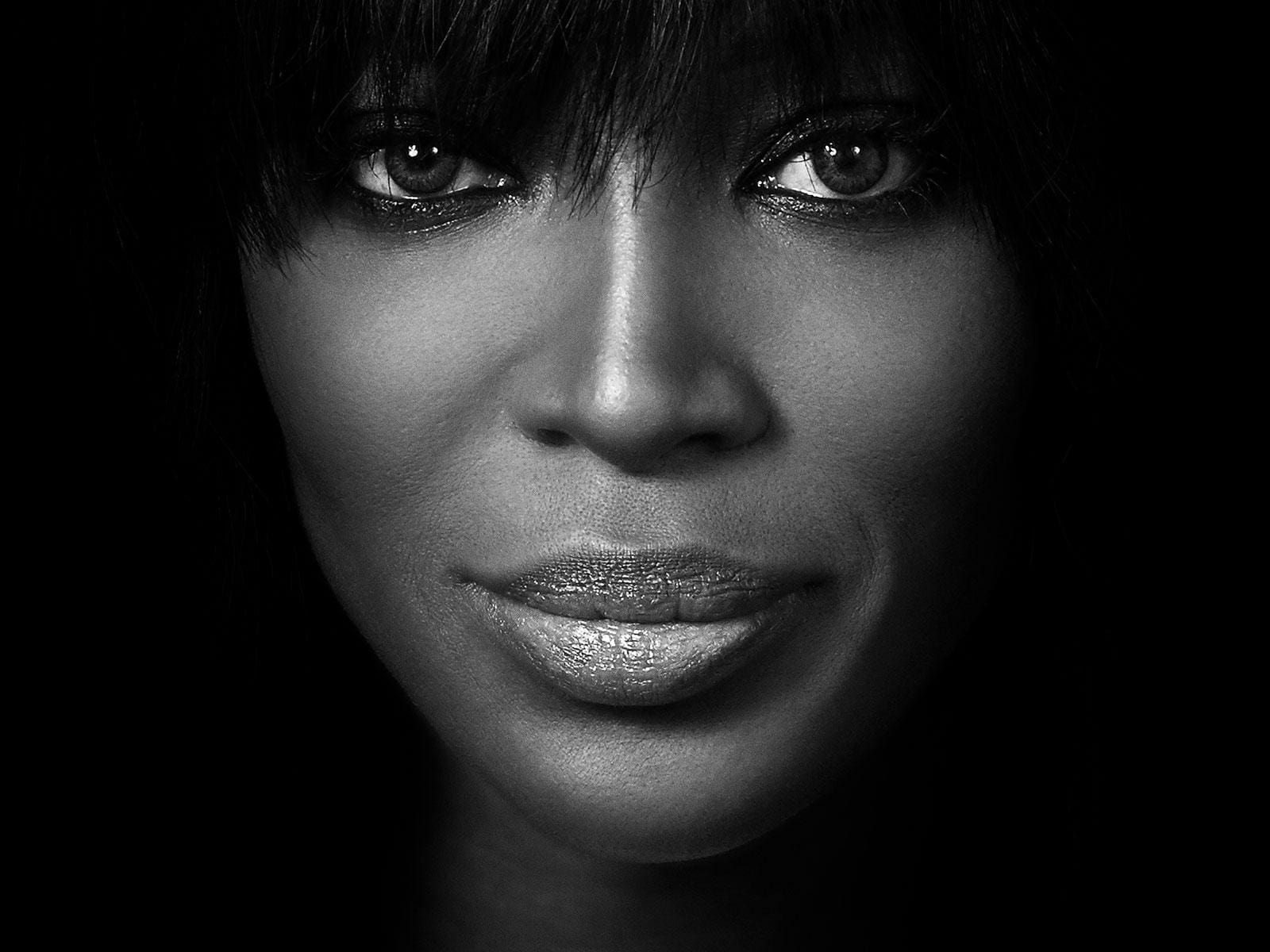

You might not recognise Andy Gotts’ name – but you’ve almost certainly seen his photos. From Oscar winners to music legends, and everyone in between, Gotts’ enormous portfolio and atmospheric, charismatic images have made him the celebrity photographer every star wants to be shot by. Quite the feat for someone who steadfastly refuses to airbrush his photos.

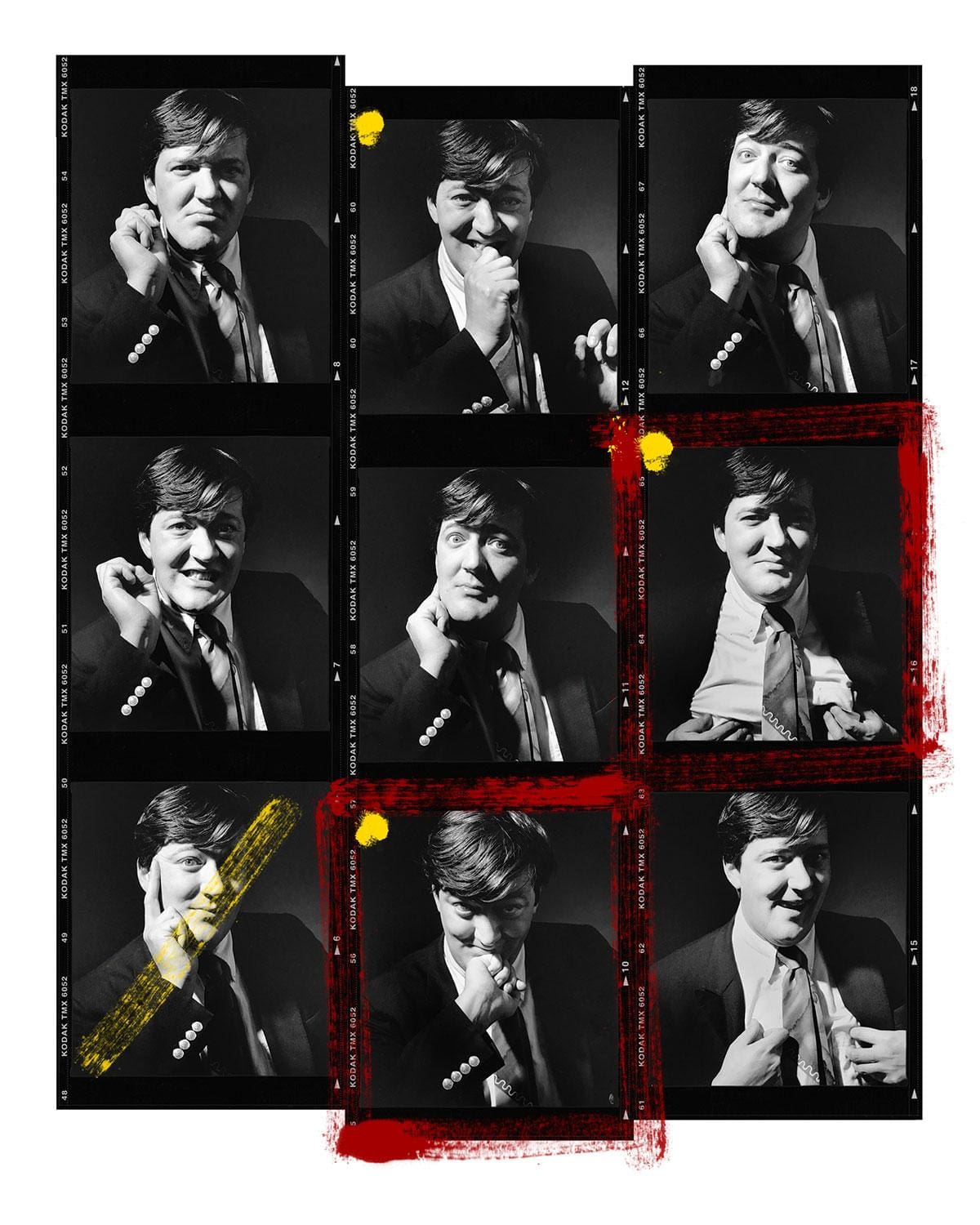

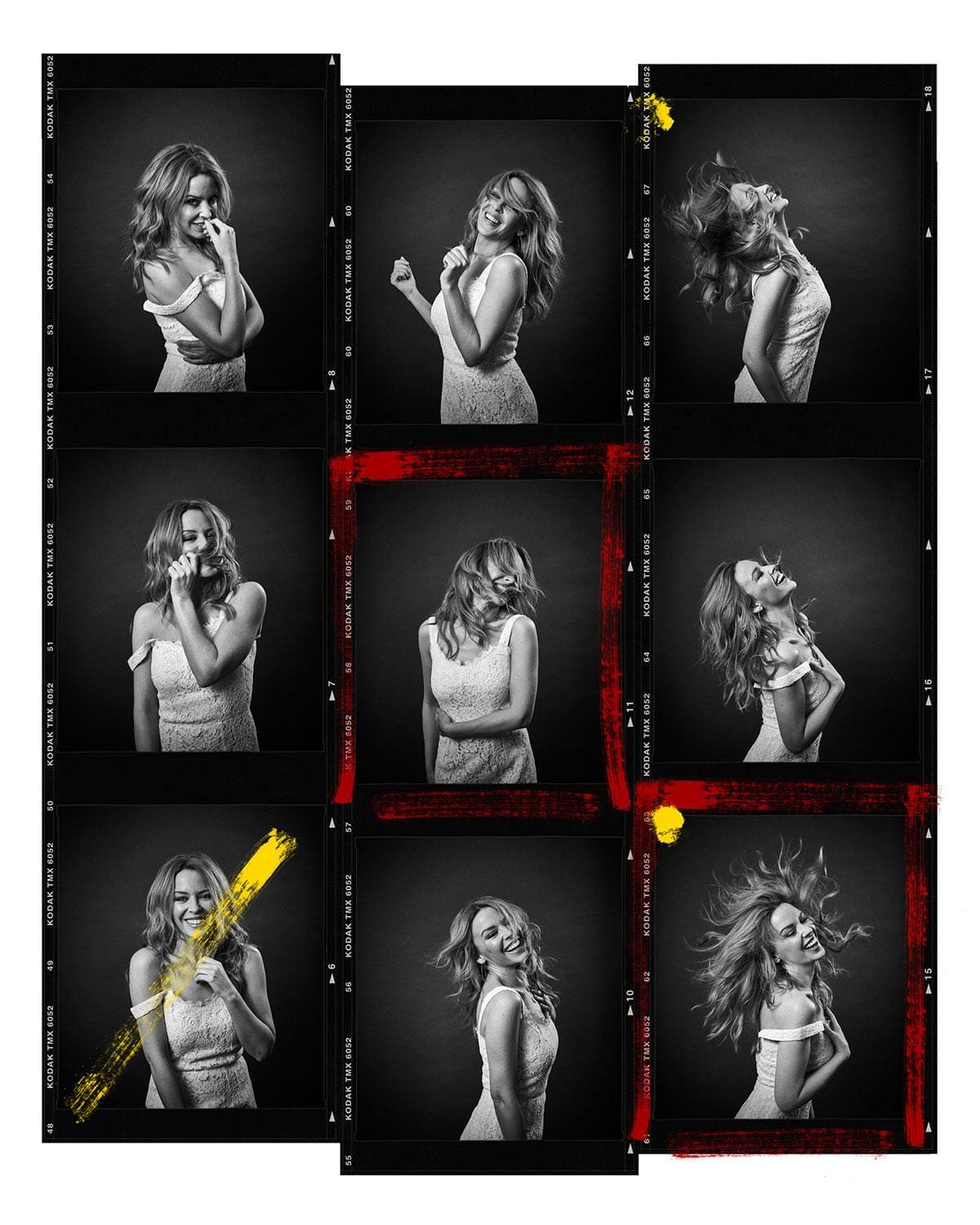

Renowned for helping famous faces reveal a more natural, unfiltered side of themselves, this September Gotts’ will bring together some of his favourite images for a new exhibition at Westbourne Grove’s Maddox Gallery. ICONS, which accompanies a new book of the same name, is a collection of both new and familiar images (many of which are accompanied by never-before-seen contact sheets) chosen by Gotts for being ‘the icons that influenced my life’.

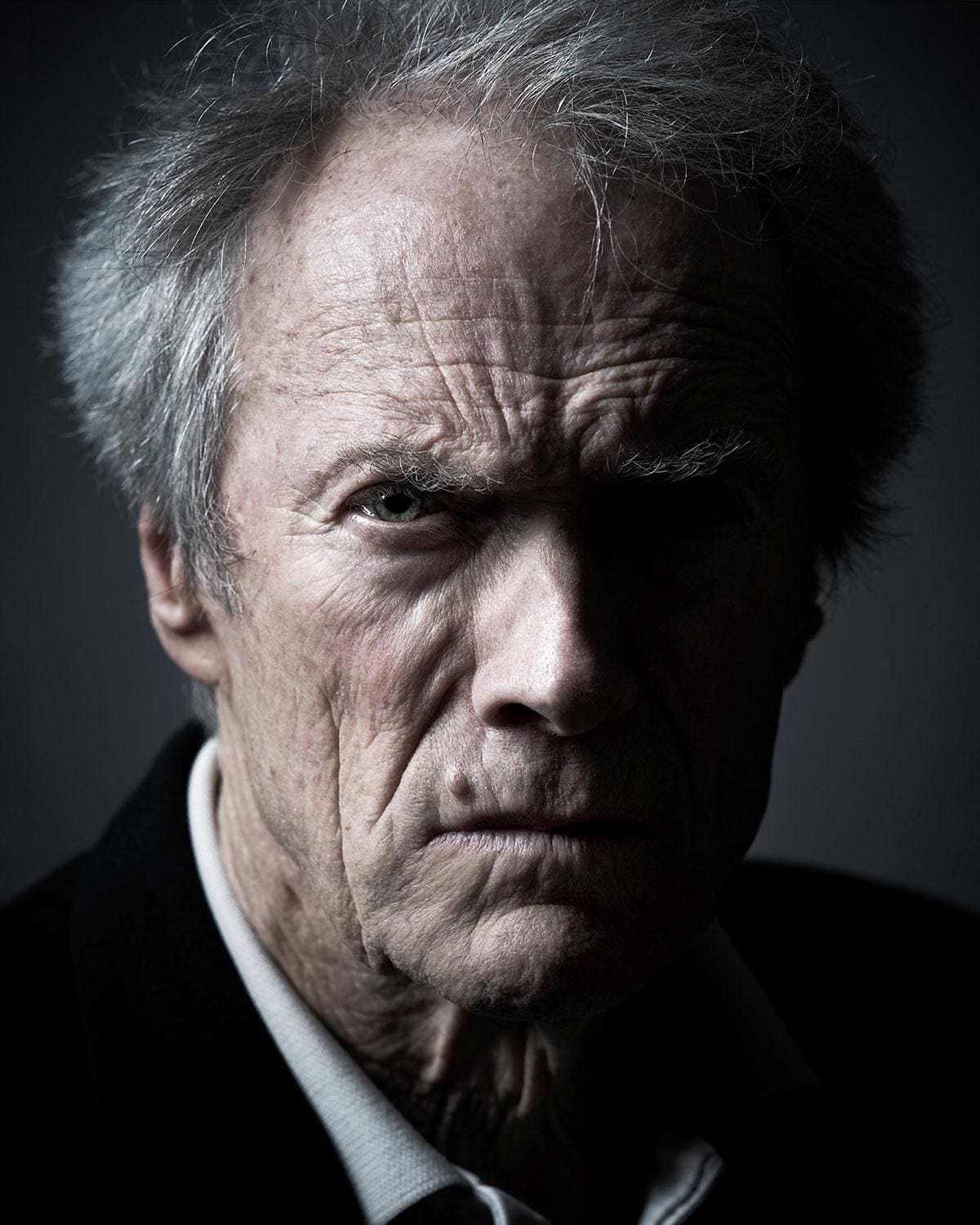

An extensive list that features Elton John, George Clooney, Kylie, Michael Caine and Robert de Niro, each image in the exhibition also represents a story – and, after 30 years spent around the world’s biggest household names, Gotts has a lot of stories to tell. Here he tells us about playing piano with Clint Eastwood, secret shoots with Monty Python and much, much more.

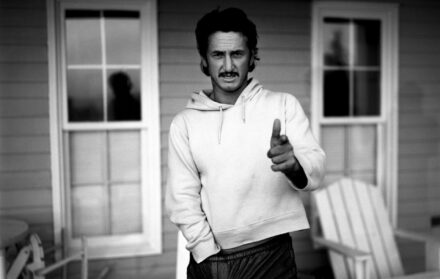

It all started in 1990. I was at the Norfolk College of Art and Technology doing a BTEC photography course. In year one they make you do fine art, landscapes, still life, fashion photography – everything – so you can choose a specialism. There was nothing I wanted to do. Then Stephen Fry came to the college to give out some diplomas and do a Q&A. In 1990, there were only four TV stations and Stephen Fry had three primetime shows every single week. He was a megastar. I found out which room the Q&A was in and set up a mini studio next door. At the end of the talk he asked if there were any questions. I shot up my hand and asked if I could take a picture of him next door. He rolled his eyes and said “be quick”. I took 10 photographs in 90 seconds and that changed my life. I had this eureka moment where somebody really famous did exactly what I told them to do. It was a massive ego trip and I loved it. I still remember that I asked him to be a school girl and tweak his nipples and he just did it.

|  |

About 15 years ago I published a book called Degrees. The idea of the book was that one famous person would suggest the next famous person to be photographed – so Brad Pitt suggested George Clooney who nominated Jackie Stewart etc. I decided to donate all the profits to diabetic research. I had no connection to diabetes but the night before I had to make a decision about the charity, I was watching the news and they were saying only 2% of research funding goes to diabetes so I thought I’d support that.

When it came out I went on This Morning, back when it was Richard and Judy, to talk about the book. Then eight or nine years later, I got an email from a woman who wanted to tell me about her daughter. The daughter was diabetic and off school because she was picked on severely for having diabetes and had tried to kill herself. She was at home watching TV the very morning I was on saying all these amazing people were giving their time for diabetics like her. Overnight her mentality changed and she went on to do a course in psychology and today works for the Samaritans talking down people on the brink of suicide. I find it incredible how, in 1990, a small act of kindness that was shown by Stephen Fry has now changed so many lives. It’s mind blowing.

|  |

Every photo has a story behind it. Often it’s not the actual photoshoot itself, it’s often what you hear at a photoshoot. I love Alice Cooper, not just his music but as a human being and a person. He is a lovely, lovely man. When I shot him he told me he used to live next door to Groucho Marx in Hollywood in the ’70s. Marx had gradually retired from public life but was a terrible insomniac. He would sometimes call Cooper at two or three in the morning and he’d go over in a dressing gown, get in bed with Groucho Marx and watch old movies with him until sunrise.

When I shot Clint Eastwood, I went to his home to do a pre-shoot meeting. He lived on this long road of big ranches and I was driving really slowly trying to figure out what a Clint Eastwood house would look like. An old lady pruning a bush spotted me and offered to get in the car to give me directions. Then we spotted another old lady with a dog and she got in too and we all went up to Eastwood’s house. He had this great long drive and when we got to the end he was waiting on the porch and invited us all in for coffee. After about 40 minutes the women left and as I was setting up for the shoot he turned and said, “Aren’t those two ladies fantastic? I’d love to have half the career they’ve had.” Completely confused I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, the short one with curly hair is Doris Day and the other is Joan Fontaine.” I had absolutely no idea.

I was really lucky over the years to shoot all of Monty Python separately. A few years after I shot Eric Idle, he rang me and explained that every seven years the Pythons get together to talk about what they’re going to do with the Monty Python money. This, he said, would probably be the last time they’d all be alive and could I come down and photograph them? At the time, Monty Python were being sued by Mark Forstater, who claimed Spamalot was his idea. He won the court case and they had to pay him £2.3 million. At the photoshoot they were talking about how to raise the money to pay him and Michael Palin suggested they get the band back together for a reunion show. The next day they called and said, “We’re going to have one last show next year, but no one can know. No one can even think there are more than three Pythons getting together.” Over the course of the next six months while they were rehearsing we had hidden photoshoots in hotel basements at 2am and meetings where they’d come in through the backdoor into the kitchen of hotels. It was very exciting.

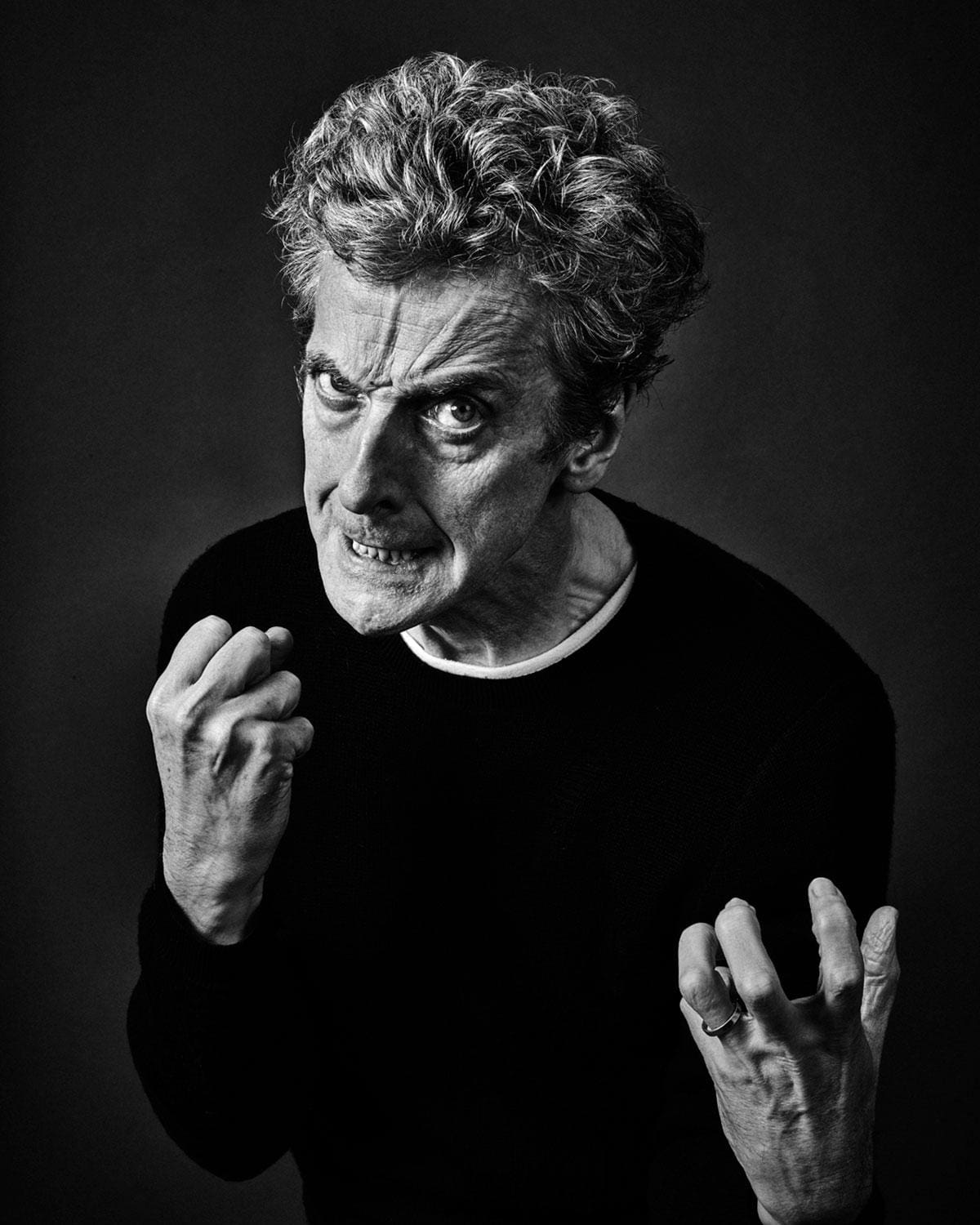

I’ve had some incredible experiences. José Carreras, who played Tony in West Side Story, Lionel Bart, who wrote the music for Oliver!, and Richard O’Brien, who did the Rocky Horror Picture Show, have all sung me their songs. I’d say the actual photography part of my job, the lighting and clicking and shooting, isn’t what makes the photo. It’s the things like this that happen around the photoshoot that make it. I’ll sing a duet with José Carreras or listen to Clint Eastwood play jazz and, by the time that’s finished, I’m on cloud nine. I’ve got all these endorphins rushing through me and I ask them to do things I probably never otherwise would have. That’s probably what has helped with the longevity of my career, I really never know what’s going to happen at any given moment and that’s great.

|  |

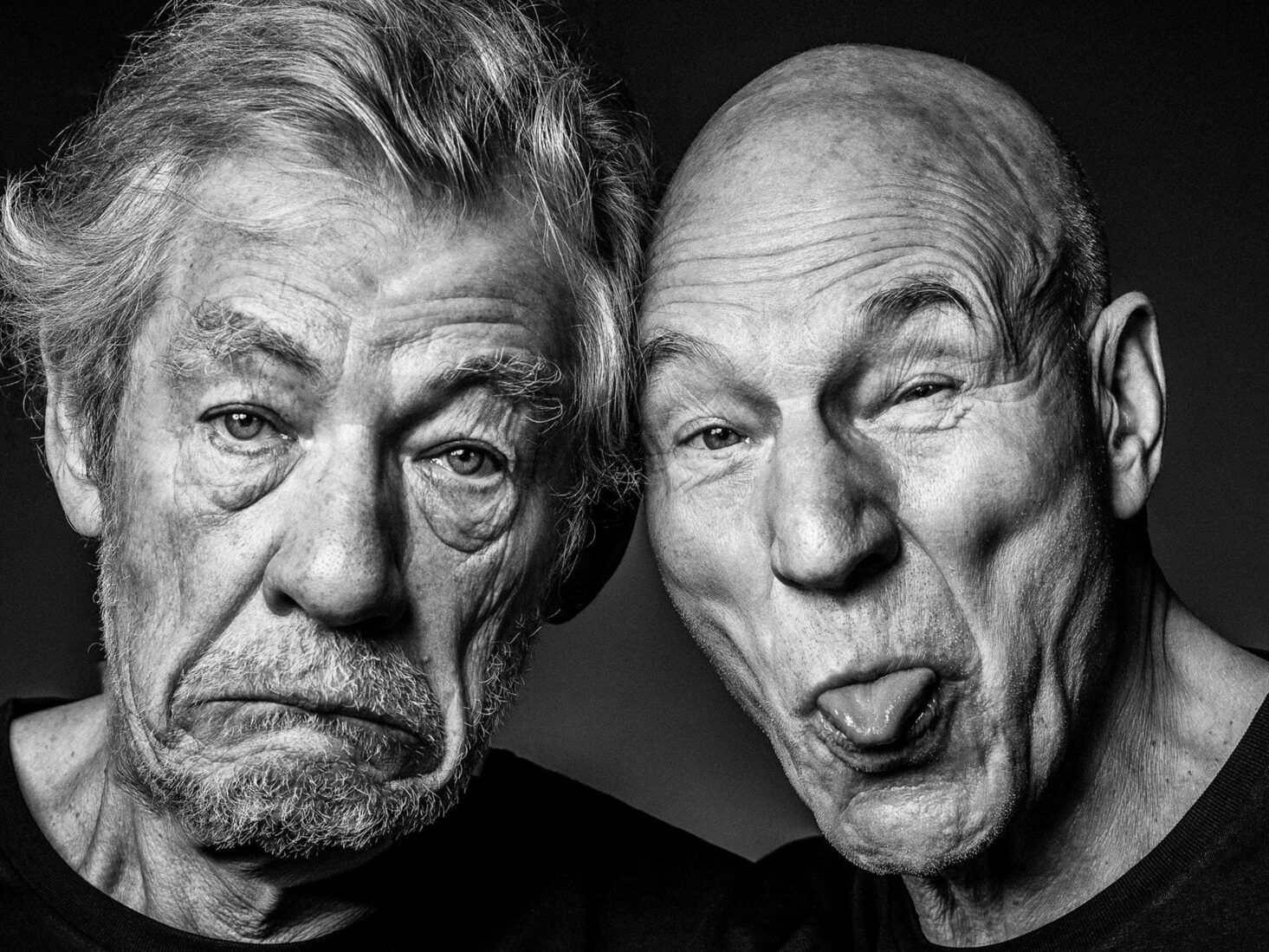

I chose never to airbrush my photos because, when I started out, everyone was doing it. I’m inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson, who co-founded Magnum Photos. He had this idea about the decisive moment: the instant when you decide to click. Either side, you get your finger on the trigger, and you wait and you wait, and you wait some more. And then you click. That, to me, is when you capture the photograph. Not on Photoshop a month later. I like the realness and the honesty of capturing every nook and cranny of the human face.

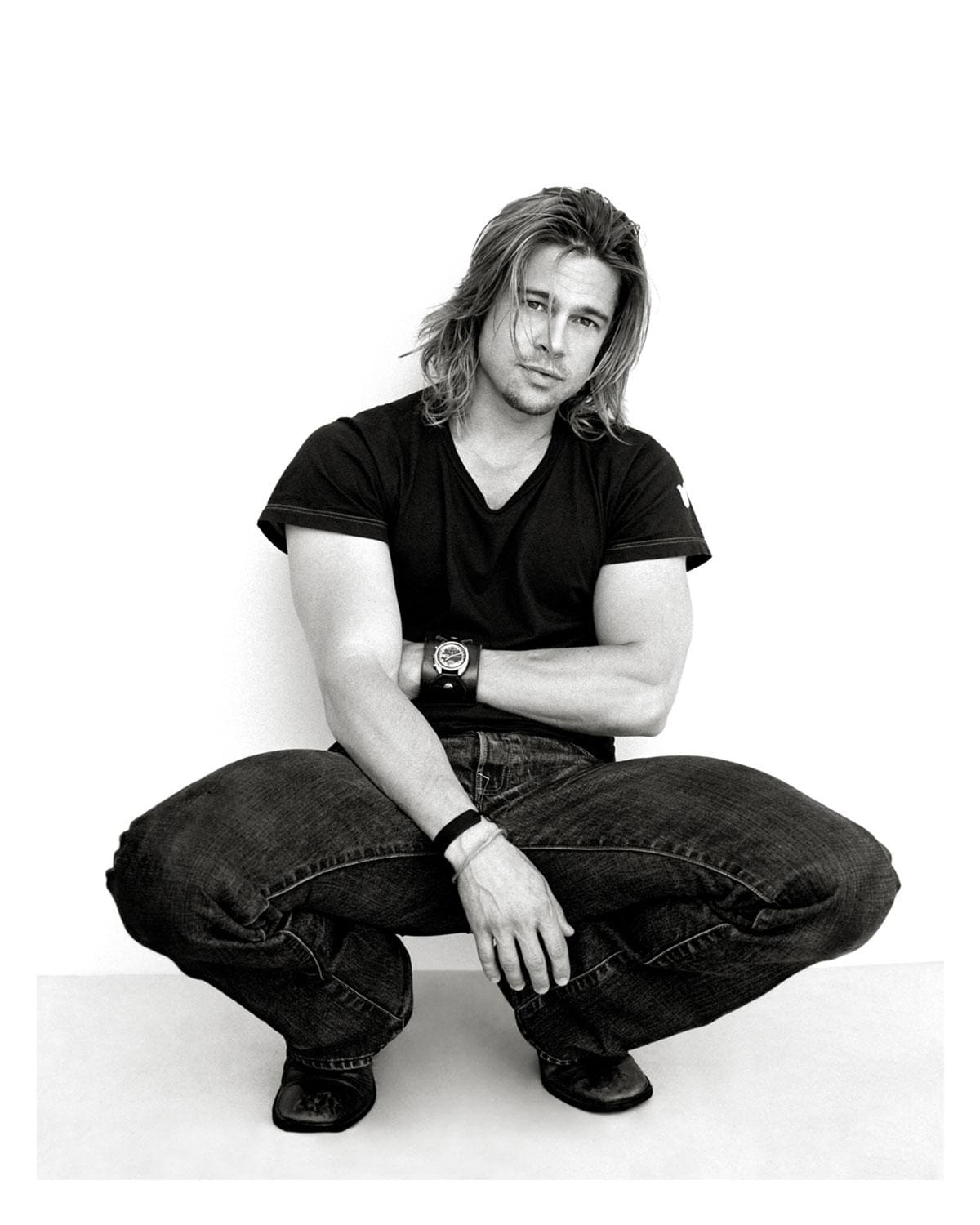

I’m not interested in making people look prettier. I’d rather capture the person in front of me in that moment in time. When I shot Brad Pitt for the first time, he was free for two days while shooting Troy. The first day he was photographed by Annie Leibowitz for Vanity Fair and she had 1,000 assistants and stylists. The next day I arrived on my own and he looked over my shoulder expecting me to have a big entourage. He couldn’t get over one person doing a shoot on their own. About a month later, I met him to show him the contact sheets and he had the pictures from the Leibowitz shoot. Bearing in mind they were taken 24 hours apart, he’d been Photoshopped so much he looked 10 years younger. It was a fantastic picture of him but he said he was happy with how he looked and he didn’t want to be made younger. I get that reaction from a lot of people I photograph.

Photographing actors who are used to being in front of a camera can be tricky. I shot Lauren Bacall not long before she passed away and she was a force of nature. She was phenomenal. She lived in the Dakota Building in New York, where John Lennon was shot, and photography is completely banned there. I had to UPS my camera equipment to her and pretend I was just a visitor to make the shoot happen. I got set up and she was talking to me about Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn while I did some quick test shots. Then I told her the shoot was starting and the Bacall facade came out. The very first picture took in the lighting test, where she’s this brooding New York grand dame, is so much better than the smiley ones that followed. It captures 89 years of life well lived.

To be a photographer you need a thick skin. A shell that’s so thick you can stand rejection for a long, long time – after all you’re not going to be a star from day one. I’d also tell any aspiring photographer not to change who you are for other people. If you have a style that represents you, don’t change it. If you have self-belief and it makes you happy, it doesn’t matter what others think.

|  |

My recipe for success is 80% luck, 10% alcohol and 10% rude jokes. That goes for every creative pursuit. No iconic artwork is what the artist set out to do. It’s down to luck: if you’re having a good day, if you mix your colours perfectly or find the right chords. It’s the same with photography. Everything is moving until you press the shutter. You never know what you’re going to get.

ICONS runs from 2-19 September 2021 at Maddox Gallery Westbourne Grove, visit maddoxgallery.com.